Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (31 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

The history

1.

Determine whether the patient currently has dyspepsia or a past history of dyspepsia (i.e. epigastric pain or discomfort, early satiation or postprandial fullness). Typical ulcer symptoms include burning or sharp epigastric pain related to meals that may wake the patient from sleep at night and is relieved by antacids or antisecretory drugs. However, many patients with these symptoms do

not

have peptic ulcer disease and ulcers are often associated with atypical symptoms. Duodenal and gastric ulcers cannot be distinguished from one another on the basis of symptoms. The differential diagnosis of dyspepsia includes gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (usually also causing heartburn or acid regurgitation), gastric cancer (especially in older patients with new onset of symptoms or with alarm features such as weight loss), biliary pain (typically severe, constant pain in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium that occurs episodically and unpredictably and lasts at least 20 minutes, but usually hours), chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer or intestinal angina (chronic mesenteric ischaemia, which causes severe postprandial pain such that the patient is afraid to eat and loses weight).

2.

Diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, hyperparathyroidism and connective tissue diseases can also cause dyspepsia.

3.

Ask about the course of the symptoms and, if intermittent, the number of recurrences and treatments given. Ask about alarm symptoms, such as weight loss (which suggests the possibility of malignancy) or recurrent vomiting (e.g. gastric outlet obstruction). Gastroparesis is rare and usually presents with recurrent vomiting, weight loss and abdominal pain.

4.

Ask about the types of investigations the patient has had undertaken in the past. If an ulcer was apparently documented, determine whether this was by endoscopy (the most sensitive and specific test) or barium meal, or just by symptoms alone (which is inadequate). Determine whether the patient knows if

H. pylori

status was determined from gastric biopsies or by non-invasive tests, such as serology, urea breath testing or stool antigen testing.

5.

A history of past ulcer surgery is important because of the associated complications (e.g. pain or bloating owing to bile reflux gastritis or an afferent loop syndrome, recurrent ulceration, early or late dumping, post-vagotomy diarrhoea, anaemia as a result of iron, vitamin B

12

or folate deficiency, and osteomalacia or osteoporosis).

6.

Ask about the family history: a strong family history of peptic ulcer may reflect the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) I syndrome.

7.

Enquire carefully about medication use – medications (e.g. digoxin, potassium, iron, oral antibiotics) can induce dyspepsia, which can be confused with peptic ulcer.

All

NSAIDs are an important cause of dyspepsia with or without chronic ulceration. Alcohol can also induce acute dyspepsia (but not chronic ulcers). Patients with an ulcer history may be taking maintenance acid suppression. First-line treatment for

H. pylori

usually includes a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus two antibiotics (amoxicillin and clarithromycin) for 7 days, but 30–40% now fail.

8.

If relevant, determine why the patient is in hospital on this occasion. If the admission is because of acute gastrointestinal bleeding, then the treatment applied needs to be documented (e.g. blood transfusion, injection of a bleeding visible vessel in a peptic ulcer base with adrenaline followed by thermal coagulation or a hemoclip; those failing endoscopy need transarterial angiographic embolisation or surgery). Remember that oral or intravenous proton pump inhibitors are routinely used and transfusions are held until the haemoglobin level drops below 70g/L (unless bleeding is massive) as survival is then better.

The examination

Physical examination in patients with suspected peptic ulcer disease is usually unhelpful. Epigastric tenderness is not a specific sign. An upper abdominal scar may indicate past ulcer surgery. Look for alarm signs, including evidence of anaemia (e.g. from bleeding) or current bleeding (melaena, tachycardia, postural hypotension) or an abdominal mass (e.g. gastric or pancreatic carcinoma).

Investigations

1.

Endoscopy

. This is the standard test for determining that an active peptic ulcer is present. It is also the key test in a patient with upper gastrointestinal bleeding to determine whether the patient is at high risk of rebleeding and also to provide endoscopic therapy where required. Patients with active bleeding or a visible vessel at endoscopy need endoscopic therapy (e.g. injection with adrenaline followed by coagulation with a heater probe). Patients with a low risk of rebleeding (i.e. a clean ulcer base) can be discharged if stable. For patients with upper gastrointestinal tract

bleeding, it is also important to exclude other causes, including variceal bleeding, erosions, angiodysplasia, a Mallory-Weiss tear or a Dieulafoy’s lesion (rupture of a large submucosal artery). Where possible, biopsies should be obtained at a diagnostic endoscopy in ulcer patients to determine the

H. pylori

status (but false negative results can occur in the setting of upper GI bleeding).

2.

Abdominal imaging

. In the patient with unexplained dyspepsia where endoscopy is normal, ultrasound can be useful in certain clinical circumstances to investigate for biliary tract pathology. CT scanning is more sensitive for pancreatic disease.

3.

Atypical peptic ulcer

. Peptic ulceration in an unusual location, peptic ulcers resistant to therapy, an ulcer relapse after operation, or frequent or early ulcer recurrence can occur in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. This syndrome can also be associated with enlarged duodenal or gastric folds, or diarrhoea or steatorrhoea. The diagnosis is made by measuring the fasting serum gastrin level: >300 pg/mL is suggestive and >1000 pg/mL is almost diagnostic. Acid secretion can be confirmed by testing the pH of gastric juice obtained at endoscopy. The next diagnostic test of choice in uncertain cases is the secretin test (if available), where a paradoxical increase in gastrin of >200 pg/mL above basal levels is highly specific. Preoperative localisation of the tumour is then attempted by CT scanning and, if necessary, angiographic venous sampling. In patients with metastatic or multifocal disease, surgery is avoided, but all other cases require surgical exploration. High-dose PPIs are used to control the disease medically.

Remember that hypergastrinaemia also occurs in hypochlorhydria (gastric pH is not acidic; e.g. in type A atrophic gastritis and pernicious anaemia, following vagotomy or in renal failure). Other causes of hypergastrinaemia with acid hypersecretion include a retained gastric antrum after peptic ulcer surgery, massive small bowel resection, gastric outlet obstruction and thyrotoxicosis. If hypercalcaemia is present in patients with ulcer disease, this may suggest MEN I (with hyperplasia, adenoma or carcinoma of the parathyroid, pituitary and pancreatic islets; hyperparathyroidism and pituitary adenoma are most often associated with the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in MEN I). In MEN I (autosomal dominant with variable penetrance), there is often a strong family history of peptic ulcer disease.

Treatment

1.

There is now consensus that if peptic ulcer disease is documented and

H. pylori

is present, this infection should be treated. Most duodenal ulcers will be cured by this approach, as will most gastric ulcers, unless associated with NSAID use.

2.

Therapy with acid suppression alone for peptic ulcer disease is now obsolete unless no cause is identified. The optimal approach for curative treatment of

H. pylori

is currently three drugs (e.g. PPI plus amoxycillin plus clarithromycin), which give cure rates of approximately 60% to 70% if given for 1 week. Side-effects occur with such treatment in up to 20% of cases.

3.

Patients with gastric ulcers may be advised to have a repeat gastroscopy to confirm healing and exclude carcinoma. However, 98% of cancers will be detected at the initial gastroscopy and biopsy. Therefore, repeat endoscopy is usually recommended only if symptoms have not been relieved or no initial biopsies were obtained.

4.

In peptic ulcer disease, confirm that

H. pylori

infection has been cured (e.g. by repeat endoscopic biopsy or urea breath testing at least 1 month after completing treatment).

5.

NSAID ulcers should initially be treated with a PPI, which is effective even if the NSAID is continued (although this does delay healing).

6.

PPIs are more effective than histamine H2-receptor antagonists in promoting ulcer healing. NSAID use is an independent risk factor for peptic ulcer and therefore eradication of

H

.

pylori

in this situation may not prevent ulcer disease if NSAIDs are continued.

7.

Certain patients taking traditional NSAIDs have a higher risk of ulcer complications. These include elderly patients, those having their first 3 months of treatment, those on higher doses, those with a past history of peptic ulcer, those taking concomitant corticosteroid therapy or anticoagulants, and those with other serious medical illnesses. NSAID ulcers often present with complications without a history of dyspepsia because these drugs are analgesic agents that may mask symptoms. The prostaglandin E1 analogue misoprostol and PPIs both substantially reduce the risk of NSAID-induced gastric and duodenal ulcers; histamine H2-receptor antagonists in standard doses do not prevent NSAID-induced gastric ulcers.

H. pylori

eradication before treatment reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of aspirin-induced ulcer development.

H. pylori

eradication alone provides insufficient protection from gastroduodenal complications arising from non-selective NSAID use in high-risk patients, who will still require a PPI.

Malabsorption and chronic diarrhoea

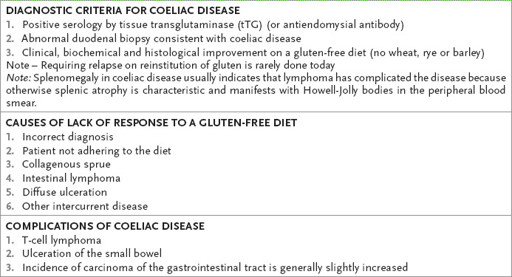

This can be a difficult long case. It is usually a diagnostic problem. Coeliac disease (

Table 7.1

), chronic pancreatitis and previous gastric surgery account for 60% of cases of malabsorption.

Table 7.1

Coeliac disease

The history

1.

Ask about presenting symptoms:

a.

pale, bulky, offensive stools (steatorrhoea)

b.

weight loss

c.

weakness (e.g. from potassium deficiency)

d.

anaemia (megaloblastic, iron deficiency, etc.)

e.

bone pain (osteomalacia)

f.

glossitis and angular stomatitis (vitamin B group deficiency)

g.

bruising (vitamin K deficiency)

h.

oedema (as a result of protein deficiency)

i.

peripheral neuropathy (owing to vitamin B

12

or B

1

deficiency)

j.

skin rash (eczema, dermatitis herpetiformis) (

Fig 7.1

)

FIGURE 7.1

Dermatitis herpetiformis – the most typical manifestation is polymorphic eruption above the elbows. S Kárpáti. Dermatitis herpetiformis.

Clinics in Dermatology

, 2012. 30(1):56–59, with permission.

k.

amenorrhoea (owing to protein depletion).

2.

Ask about the time of onset of symptoms and their duration.

3.

Ask aetiological questions concerning:

a.

gastrectomy, other bowel surgery

b.

history of liver or pancreatic disease

c.

drugs (e.g. alcohol, neomycin, cholestyramine)

d.

history of Crohn’s disease

e.

previous radiotherapy

f.

gluten-free diet treatment at any stage

g.

history of diabetes mellitus

h.

risk factors for HIV infection.