Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (22 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

7.

Ask about investigations performed, such as chest X-ray changes (the only abnormal finding in 5% of cases), CT scans, bronchoscopy, sputum cytology, needle biopsy and thoracotomy. The finding of a solitary nodule on a chest X-ray must be investigated but benign causes include a post-infection granuloma or a hamartoma.

8.

Enquire about the patient’s work and home environments, including the number of dependants and the patient’s ability to work.

9.

Ask about treatment off ered and begun.

10.

Find out the patient’s understanding of the condition and the likely prognosis.

The examination

1.

Finger clubbing is a most important sign (

Table 16.11

). This is very rare in small cell carcinoma.

2.

Chest signs will vary – listen carefully for a fixed inspiratory wheeze over a large bronchus.

3.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy may have caused hoarseness, and phrenic nerve paralysis may have caused an elevation of a hemidiaphragm.

4.

An apical tumour may be responsible for Pancoast’s syndrome (C8, T1 thoracic nerve destruction or compression, or Horner’s syndrome, or both).

5.

Look for metastatic (e.g. supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and hepatomegaly) and non-metastatic manifestations, especially the neurological and endocrinological changes (

Table 6.4

).

Investigations

Screening of high-risk patients with chest X-ray or CT scanning may lead to an early diagnosis, but has not been shown to affect survival. The diagnosis may be difficult, even when suspected.

1.

Sputum cytology may be helpful in centrally located lesions, but fibre-optic bronchoscopy is now more often done first.

2.

The chest X-ray or CT may suggest the cell type: for example, peripheral nodule adenocarcinoma; central lesion with obstructive pneumonitis – squamous; mediastinal or hilar mass – small cell; or alveolar infiltrate – bronchoalveolar cell.

3.

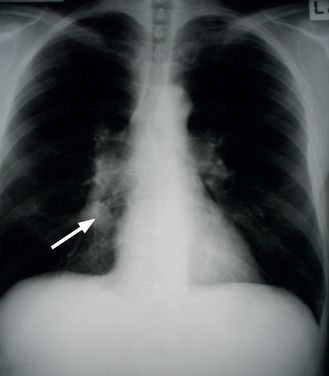

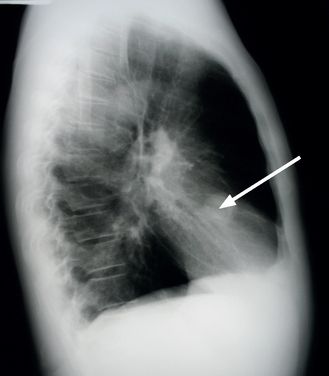

A suspect shadow on the chest X-ray film should be investigated by fibre-optic bronchoscopy and biopsy or fine-needle aspiration (see

Fig 6.2a and b

). Bronchial brushings and washings, taken at bronchoscopy, should also be sent for cytological examination but have a lower yield than biopsy.

FIGURE 6.2

(a) PA film. A round opacity is visible in the right middle lobe (arrow).

(b) Lateral film. A round opacity is visible in the right middle lobe (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

4.

For peripheral lesions, especially those less than 2 cm in size, transthoracic fine-needle biopsy with CT guidance is very useful, but complications (e.g. pneumothorax, significant bleeding) can occur.

5.

In patients with a malignant pleural effusion, thoracocentesis and pleural biopsy provide a high diagnostic yield (

Table 16.12

).

6.

Other investigations may include bone marrow biopsy, mediastinoscopy and thoracotomy. Video-assisted thoracoscopy has replaced open biopsy in many centres.

7.

Other possible causes (e.g. of a coin lesion) must be excluded. For this purpose CT is helpful; demonstration of central or lamellar calcification usually indicates that a coin lesion is benign. Follow-up scans to confirm a lesion is unchanged are helpful. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans may be of value in these cases.

8.

Once the diagnosis is made and the cell type identified, further investigations may be indicated to stage the disease.

•

Symptoms and signs that suggest central nervous system, liver, bone, chest wall or mediastinal involvement need to be sought carefully.

•

Full blood count (

Table 6.5

), serum calcium and liver function tests may suggest tumour spread.

Table 6.5

Full blood count and liver function tests from a female patient with carcinoma of the lung

| PARAMETER | VALUE | NORMAL VALUE |

| Haemoglobin | 84 g/L | 115–165 g/L (female) |

| Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) | 95 fL | 80–100 fL |

| White cell count (WCC) | 4.0 × 10 9 /L | 4.5–13.5 × 10 9 /L |

| Platelets | 95 × 10 9 /L | 150–400 × 10 9 /L |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) | 70 mm/h | 3–19 mm/h (female <50 years) |

| Bilirubin | 84 mmol/L | <20 mmol/L (total) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 57 U/L | <40 U/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 50 U/L | <35 U/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 780 U/L | 110–230 U/L |

| Protein | 60 g/L | 62–80 g/L (total) |

| Albumin | 33 g/L | 32–45 g/L |

Blood film:

normochromic red cells, poikilocytosis, tear drop cells. Some nucleated red cells (normoblasts) and myeloid cells (metamyelocytes and myelocytes). Some rouleaux formation.

Comment:

The combination of normochromic anaemia and the presence of marrow precursors in the peripheral blood is called a leucoerythroblastic reaction. It is typical of bone marrow infiltration by carcinoma or fibrosis. The abnormal liver function tests are non-specific, but suggest liver involvement in this setting. The elevated LDH level probably indicates liver damage, but can also occur when there is haemolysis.

•

CT scanning of the chest and abdomen with contrast is an important aid in determining whether disease is localised.

•

In small cell carcinoma, stage the disease into limited disease (lung primary, ipsilateral and contralateral hilar, mediastinal and supraclavicular nodes) or extensive disease −70% of patients (contralateral lung, distant metastases).

•

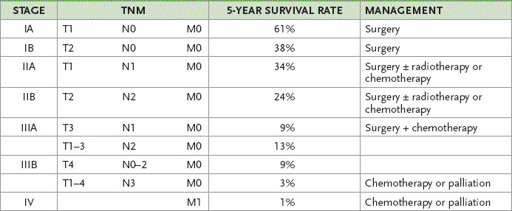

Non-small cell carcinoma is staged according to the tumour node metastases (TNM) international staging system (

Table 6.6

). In general, disease confined to one hemi-thorax and the ipsilateral cervical nodes is called

limited

and further involvement is described as

extensive

disease.

Table 6.6

TNM international staging system for carcinoma of the lung (non-small cell)

T1–T4 = ascending degrees of increase in tumour size and involvement; N0 = no lymph nodes;

N1–4 = ascending degrees of nodal involvement; M0 = no metastases; M1–4 = ascending degrees of metastatic involvement.

9.

Assessment for resectability should include respiratory function tests. If the forced expiratory volume (FEV

1

) is 1.5 L or more, this indicates that the patient could tolerate a pneumonectomy (a postoperative FEV

1

of 1 L or more is usually considered the minimum that will be tolerated). Otherwise, a patient who can climb three flights of stairs is usually considered well enough to tolerate surgery.

Treatment

The average 5-year survival rate for all types of carcinoma of the lung is about 15%.

Small cell carcinomas

1.

These are only occasionally resected as they have usually metastasised at the time of diagnosis. They are, however, sensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

2.

In patients with limited disease, chemotherapy and concurrent radiotherapy improve the prognosis. Untreated, the median survival is only about 4 months. Treatment often includes platinum-based drugs – etoposide and cisplatin or carboplatin.

3.

Prophylactic cranial irradiation may be given to patients with complete responses. There is a risk of leukaemia, central nervous system metastases, dementia and second primary malignancies with treatment.

Limited small cell carcinoma has a median survival with treatment of 11–18 months; 10–20% are disease-free at 2 years. Extensive small cell carcinoma has a median survival of 6–12 months with therapy.

Non-small cell carcinomas

1.

These may be resectable – unless tumour has spread to the contralateral lung or outside the thorax or there is significant cardiopulmonary disease.

2.

The most important prognostic factor is the stage of disease. Staging usually involves bronchoscopy and CT scanning of the chest, abdomen and brain, (PET scanning is useful but not covered by Medicare for this indication), as well as a physiological assessment of the patient’s fitness for surgery, from the point of view of both lung function and general health. One-third of patients have disease sufficiently localised for an attempt at resection.

3.

Radiotherapy with ‘curative intent’ may be offered to patients if they refuse surgery or are unfit for surgery for other reasons. About 6% are alive after 5 years. Radiotherapy is not useful for patients who have had surgical resection of a peripheral tumour.

4.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is not routine for surgical patients, but regimens including cisplatin may provide a small survival advantage (5% at 5 years). A common regime involves four cycles over 12–16 weeks. Median survival is only a few months in patients with intracranial metastases or bone involvement.

5.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are used for stage IV disease. Although these patients will succumb to the disease, there is evidence that this can prolong life and improve symptoms. Treatment is often guided by tumour characteristics – pemetrexed-based chemotherapy is preferred for non-squamous tumours. Some tumours have mutations at the tyrosine kinase domain and the use of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (gefitnib and erlotib) has been associated with an initial improved response. Resistance usually develops after about a year of treatment.

6.

Airway obstruction as a result of carcinoma may be relieved by using Nd-YAG laser or brachytherapy for palliation.

7.

Combination chemotherapy is sometimes appropriate. Survival benefit is only 1 or 2 months.