Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (101 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Note:

Drugs (e.g. clofibrate) can also cause myotonic discharges on EMG, but do not cause clinical myotonia.

4.

Examine the arm now for signs of wasting and weakness, especially of the forearm muscles. Sensory changes from the associated peripheral neuropathy are usually very mild.

5.

Go to the chest and inspect for gynaecomastia.

6.

Ask to palpate the testes for atrophy.

7.

Examine the lower limbs if there is time.

8.

Always ask to test the urine for sugar (diabetes mellitus is more common in this disease) and to examine the cardiovascular system for cardiomyopathy. Finally test mental status (mild mental retardation is usual).

HINT

Remember the classic EMG finding in dystrophia myotonica of a ‘dive bomber’ effect with needle movement in the muscle at rest.

Gait

‘Please examine this man’s gait.’

Method (see

Table 16.57

)

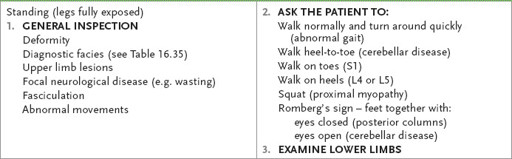

Table 16.57

Gait examination

1.

Scan the room for a walking stick or frame or special shoes.

2.

Make sure the patient’s legs are clearly visible. Ask him to ‘hop out’ of his bed or chair (look carefully while he is doing so for focal disease), watch him walk normally for a few metres and then ask him to turn around quickly and walk back towards you.

3.

Next ask him to walk heel-to-toe to exclude a midline cerebellar lesion.

4.

Ask him to walk on his toes (an S1 lesion will make this difficult) and then on his heels (a lesion causing foot drop will make this difficult).

5.

Test for proximal myopathy by asking the patient to squat and then stand up, or sit in a chair and then stand.

6.

Look for Romberg’s sign (posterior column loss causes inability to stand steadily when the feet are together with the eyes closed, whereas cerebellar disease causes difficulty when the eyes are open too).

7.

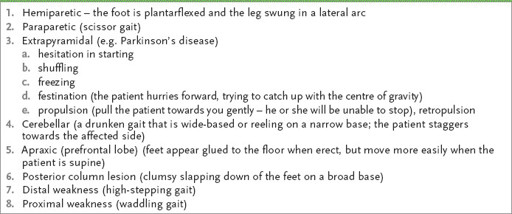

Go on to examine the lower limbs depending on your findings. The typical gaits to recognise are listed in

Table 16.58

.

Table 16.58

Typical gaits

Cerebellum

‘This 30-year-old man has noticed a problem with his coordination. Please examine him.’

Method

This patient is likely to have a cerebellar problem (see

Table 16.59

). The only other likely possibilities are posterior column loss or extrapyramidal disease. Proceed as follows for assessment of cerebellar disease.

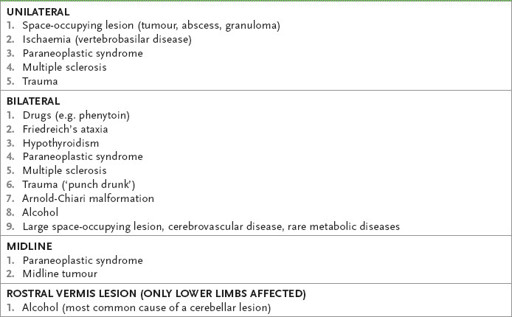

Table 16.59

Causes of cerebellar disease

1.

Test gait (the patient will stagger towards the affected side unless the problem is bilateral or involves the vermis).

2.

Go on to examine the legs. Test tone here.

3.

Ask the patient to perform the heel–shin test, looking for accuracy of fine movement when the patient slides his heel down the shin quickly on each side for several cycles.

HINT

If cerebellar testing seems normal but Romberg’s test was positive, test position and vibration sense.

4.

Next ask the patient to lift his big toe up to touch your finger, looking for intention tremor. Ask him to tap each foot rapidly on a firm surface.

HINT

Subtle cerebellar changes may be obvious only if the test is made more difficult. Ask the patient to lift the leg in an arc before placing it back on the top of the shin.

5.

Look now for nystagmus, usually jerky horizontal nystagmus with an increased amplitude on looking towards the side of the lesion.

6.

Assess speech. Ask the patient to say ‘British Constitution’ or ‘West Register Street’. Cerebellar speech is jerky, explosive and loud, with irregular separation of syllables.

7.

Go to the upper limbs. Ask the patient to extend his arms and look for arm drift and static tremor as a result of hypotonia of the agonist muscles. Test tone. Hypotonia is caused by loss of a facilitatory influence on the spinal motor neurones in acute unilateral cerebellar disease.

8.

Next ask the patient to perform the finger–nose test – the patient touches his nose, then rotates his finger and touches your finger. Note any intention tremor (erratic movements increasing as the target is approached owing to loss of cerebellar connections with the brain stem) and past pointing (the patient overshooting the target).

9.

Test rapid alternating movements; the patient taps alternately the palm and back of one hand on his other hand or thigh. Inability to perform this movement smoothly is called dysdiadochokinesis.

10.

Test rebound – ask the patient to lift his arms quickly from the sides and then stop. Hypotonia causes the patient to be unable to stop his arms. Always demonstrate each movement for the patient’s benefit, asking him to copy you.

11.

Look for truncal ataxia by asking the patient to fold his arms and sit up. While he is sitting, ask him to put his legs over the side of the bed, and then test for pendular knee jerks.

12.

If there is time, look for possible causes of the problem. If there is an obvious unilateral lesion, auscultate over the cerebellum, then proceed to the cranial nerves and look for evidence of a cerebellopontine angle tumour (fifth, seventh, eighth cranial nerves affected) and the lateral medullary syndrome.

13.

Always look in the fundi for papilloedema.

14.

Next examine for peripheral evidence of malignant disease and vascular disease (carotid bruits).

15.

If there is a midline lesion only (i.e. truncal ataxia or abnormal heel–toe walking or abnormal speech), consider either a midline tumour or a paraneoplastic syndrome. If there is bilateral disease, look for signs of multiple sclerosis, Friedreich’s ataxia (pes cavus being the most helpful initial clue) (see

Tables 16.60

and

16.61

) and hypothyroidism (rare). Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration (which affects the anterior lobe of the cerebellar vermis) classically spares the arms.

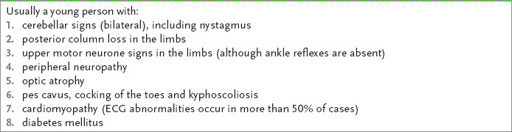

Table 16.60

Clinical features of Friedreich’s ataxia (autosomal recessive)

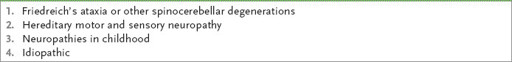

Table 16.61

Causes of pes cavus

16.

If there are, in addition, upper motor neurone signs, consider the causes in

Table 16.62

.

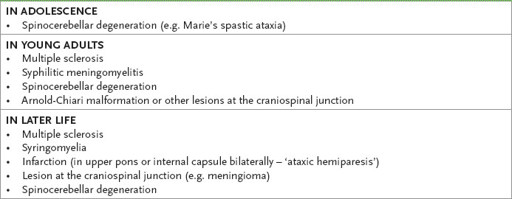

Table 16.62

Causes of spastic and ataxic paraparesis (upper motor neurone and cerebellar signs combined)

Don’t forget, common unrelated diseases (e.g. cervical spondylosis and cerebellar degeneration from alcohol) may occur together by chance.

Parkinson’s disease

‘This 80-year-woman has Parkinson’s disease. Please assess the severity of the condition.’

Method

1.

Look at her first. Note the obvious lack of facial expression (‘mask-like’) and paucity of movement.

2.

Ask her to walk, turn quickly and stop, and restart. Note particularly difficulty starting, shuffling, freezing and festination. It is probably a little dangerous to look for propulsion or retropropulsion (see

Table 16.58

).

3.

Ask the patient to return to bed and look for a resting tremor with the arms relaxed (see

Table 16.63

). The characteristic movement is described as pill rolling and may be unilateral early on.

Table 16.63

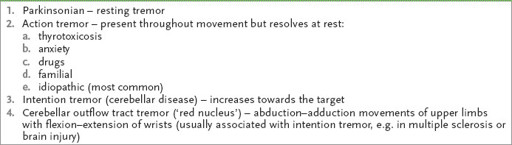

A classification of tremor