Everything Kids' Magical Science Experiments Book (16 page)

Read Everything Kids' Magical Science Experiments Book Online

Authors: Tim Robinson

Tags: #epub, ebook

Everyone knows that to store water in a jar, you simply open the lid and pour it in. But if you turn the jar upside down, you'll have a big mess on your hands. No one wants a puddle of water on the floor, so instead, you can try this experiment. By reducing the air pressure inside the jar, you can pull water up into the jar and keep it there. What's more, you can test different jars and different types of candles to see which combination draws the most water up into the jar.

Question: How can a candle fill a jar with water?

In this experiment, you will place a candle in a pan of water. You will then light the candle and cover it with a glass jar. When the flame goes out, the water will magically be sucked up into the jar. Until you remove the jar from the pan, the water will stay there. You task is to test various candle shapes, sizes, and heights, to see which allows the greatest amount of water to be sucked up into the jar. You will also be able to test different types of jars (glass only) to see whether jar shape has any effect on the amount of water that can be pulled up. Be sure when doing this experiment that you only change one variable at a time. If you change more than one part of your experiment, you won't know which one caused the effect you observe.

The pressure of the outside air, called atmospheric pressure, is 14.7 pounds per square inch. That means that for every square inch of flat surface, the weight of all the air above it is 14.7pounds.

We know that gravity makes objects fall to the ground. In general, water obeys this law. However, when the pressure is strong enough, water can actually overcome the effects of gravity and move upward into the jar. This only happens when the air inside the jar is removed or reduced to the point that outside air pressure can push the water up into the jar. Atmospheric pressure is constantly pushing down on the water in the pan. If you were to place the jar over an unlit candle, the pressure on the water inside the jar would be the same as the pressure on the water outside the jar. Only when the candle burns up and consumes some of the oxygen inside the jar does the air pressure inside drop. This lower air pressure cannot overcome the outside air pressure and the water is forced up into the jar.

- Glass or metal pie plate

- Several glass bottles of different heights and diameters

- Several candles of various sizes, shapes, and heights

- Water

- Marking pen

- Fill the pie plate with water.

- Place the candle in the middle of the plate, taking care that the top of the candle sits above the surface of the water.

- Place the jar, mouth down, over the candle to verify that the water level inside the jar is the same as the water level outside the jar.

- Remove the jar and light the candle.

- Replace the jar over the candle. Watch as the candle goes out and the water is sucked up into the jar.

- When the water level inside the jar stops rising, use your pen to mark the water height.

- Carefully remove the jar from the water. The extra water in the jar will pour back into the pie plate.

- Repeat steps 2â6, either with a different candle or a different jar. Each time you produce a new mark on the jar, record the diameter and height of the jar and candle.

- When you have completed all your tests, analyze your data to determine which combination of jar and candle produced the greatest effect on the water.

- What type of jar was the most effective for drawing water up in this experiment?

- How might the jar diameter mislead you to think that one jar pulled up less water than another, when in fact it may have pulled more?

- What type of candle was most effective for drawing water up in this experiment?

- What effect might the water temperature have on your results in this experiment? Would warm water react differently than cold water?

You can build a home version of a barometer using a setup similar to this one. By placing a bottle inside a container of water, you can measure the changes in the water height each day as the atmospheric pressure changes. The higher the atmospheric pressure, the higher the water will rise inside the bottle. This concept is similar to the way atmospheric pressure is reported by television news. You may hear something like this: the pressure is 29.9inches and rising. This is actually a measure of how high mercury would rise in a formal barometer. Good weather is typically associated with high pressure, while lower pressure often brings bad weather. In your experiment, the lower pressure inside the jar made the outside air pressure seem “high,” which caused the water to rise into the jar.

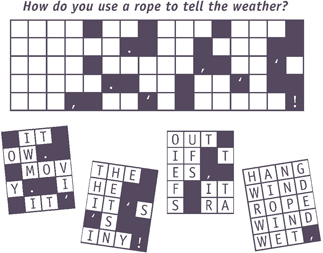

Meteorologists use a lot of high-tech scientific equipment to predict the weather. But you can use something much more simple â a piece of rope! To find out how this “magic” weather predictor works, figure out where the puzzle pieces go, and write the letters into the empty grid.

Demo version limitation

Web sites

http://pbskids.org/zoom/activities/sci

http://pbskids.org/zoom/activities/sci

www.surfnetkids.com/directory/Science

www.surfnetkids.com/directory/Science

www.pbskids.org/zoom/activities/do/magictricks.html

www.pbskids.org/zoom/activities/do/magictricks.html

Churchill, E. Richard, Louis V. Loeschnig, Muriel Mandell, and Frances Zweifel.

365 Simple Science Experiments

(New York: Sterling Publishing Company, 2000).

Hauser, Jill Frankel, and Michael P. Kline.

Science Play!: Beginning Discoveries for 2- to 6-Year Olds.

(Charlotte, VT: Williamson Publishing Company, 1998).

Potter, Jean.

Science in Seconds for Kids: Over 100 Experiments You Can Do in Ten Minutes or Less

(San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

Odyssey Magazine

National Geographic Kids

www.kids.nationalgeographic.com

www.kids.nationalgeographic.com

YES magazine

Dig: The Archaeology Magazine for Kids