End Procrastination Now! (15 page)

Read End Procrastination Now! Online

Authors: William D. Knaus

Step 3: Prepare and gather information to create a plan that you can modify with new information.

As you actively engage in this constructive process, you can build momentum for other preparatory steps further down the line.

Step 4: Actively work to develop a time perspective for proactive coping, or the process may get caught up in the same time vortex as other delayed activities.

A commitment about when you'll start and what you'll do first can start the process in motion and make the difference. Apply challenge language about how, when, and where you'll proactively cope.

When you arrive at the meeting, you are unlikely to have all the answers. The purpose of the meeting is to flesh out the issues and come to reasoned conclusions. However, when you are prepared, you are likely to see the meeting as a challenge. You don't feel the usual stress and strain where you hope to go unnoticed in the meeting.

Low frustration tolerance is a strong aversion for tension that can lead to discomfort dodging and procrastination. This sensitivity to unpleasant sensations gets worse when it is magnified by self-talk, such as, “The task is too tough, and I can't stand doing it.” These tension-amplifying thoughts are a slippery slope to procrastination practices. Questions such as what makes the task too tough and why you can't stand what you don't like can expose the false evaluative dimension of this thinking.

Building high frustration tolerance is a significant life challenge. If you don't fear or avoid tension, you are likely to feel that you are in command of yourself and of the controllable events that take place around you. Paradoxically, you are also less likely to experience amplified tensions when you don't fear them. With high frustration tolerance, you are likely to take on more challenges and experience more accomplishment and satisfaction from the actions that you undertake. Building and using counter-procrastination skills helps decrease tension fears as you boost your self-efficacy skills.

Tension avoidance through procrastination practically always involves an evaluation. Exaggerated evaluations about discomfort tend to lead to discomfort dodging. The evaluations that lead to discomfort dodging tend to interact with self-doubts and increase vulnerability to procrastination. If you reduce either your self-doubts or your intolerance for tension, you've acted to reduce both conditions along with weakening a co-occurring procrastination habit.

Frustration-tolerance training can be counted among the most powerful ways to reduce both stress and procrastination that is associated with stress and that sets conditions for added stress. Here are three broad directions:

1.

Build your body

to buffer pressures from multiple ongoing frustrations. Ongoing stress increases the risk of disease, fatigue, and mood disorders, and so building your body has an added value in reducing these risks. Build this buffer through regular exercise; a healthy diet; maintaining a reasonable weight for your gender, height, and age; and getting adequate sleep.

2.

Liberate your mind from ongoing stress thinking

. This includes dealing with pessimistic and perfectionist thinking as well as low-frustration-tolerance self-talk, such as telling yourself something like, “I can't take this; I have to have relief right now.”

3. Change patterns that you associate with needless frustration, such as holding back on going after what you want, avoiding contention at all costs, and inhibiting yourself from engaging in the normal pursuits of happiness and from actions to curb procrastination.

(For more information on frustration-tolerance development, I've provided a free e-book. To access the book, visit

http://www.rebtnetwork.org/library/How_to_Conquer_Your_Frustrations.pdf

.)

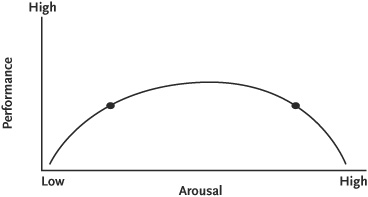

Since stress is inevitable, why not accept this reality and figure out how to make stress work for you? The Yerkes-Dodson curve shows

the proven relationship between arousal and performance that you can use to put threat and challenge into a visual perspective while adding an undermotivated dimension (see Figure 4.1).

The slope at the extreme left of the curve shows low arousal and motivation. The slope at the extreme right shows the effects of negative thinking. The region between the two dots in the middle shows an optimal range of arousal. However, some productive activities involve different levels of arousal. Answering a phone and finishing a Masters in Business Administration degree take different levels of arousal. However, the curve is quite okay as an awareness tool for putting arousal into perspective.

If you have a low arousal level for a high-priority activity, your challenge is to either push yourself to start and finish or find an incentive. Pushing yourself is a form of arousal. A possible motivating incentive is to get an unwanted task off your back.

If your mind is filled with threat stress thoughts, you'll probably have trouble solving a complex problem. When tension is at the extreme, it can be so distracting and disorganizing that you seem to have little time and energy to do anything else. The challenge is to “take a breather,” such as a walk around the block. Plan to shift to a self-observant perspective, perhaps by recording and organizing what is going on using the ABCDE problem-solving format. This organization initiative actively sets the stage for engaging the problem with a clearer, calmer, mind and a directed sense of purpose.

FIGURE 4.1

The Yerkes-Dodson Curve

END PROCRASTINATION NOW! TIP

The POWER Plan

P

roactively cope with upcoming challenges by setting a design for achievement.

O

utline a commitment and challenge thinking approach to support proactive coping.

W

ork to execute a coping program to operate productively and reduce stress.

E

valuate your progress and not yourself.

R

epeat this proactive challenge and commitment thinking approach until it feels natural.

The curve serves as a reminder of the benefits of challenge arousal and that this arousal is healthy. Indeed, much learning and remembering is motivated by adaptive forms of tension.

Breaking the procrastination habit takes work, and this is best done by working at what you put off. There is another dimension to this: when procrastination is a symptom of distressing thinking, the most direct line to freedom is to follow through without diversion; evaluate this thinking using Socrates', Frankl's, and Ellis's prescriptions. If these ways aren't successful, try another.

You can learn to buffer yourself against stress conditions that coexist with procrastination conditions such as anxiety, catastrophizing, and feeling overwhelmed. What will work best for you?

What three ideas have you had that you can use to help yourself deal with procrastination behaviors effectively? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What is your action plan? What are the three top actions you can take to promote purposeful and productive outcomes? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What implementation actions did you take? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

What three things did you learn from applying the ideas and the action plan, and how can you next use this information? Write them down.

1.

2.

3.

The Behavioral Approach: Follow Through to Get It Done

5

Act Decisively

Aconscious decision to act decisively is the first step in initiating behavioral follow-through. Once you've become aware of triggers that cause habitual procrastination, you've emotionally coped with the unpleasant task, you've made an active decision to get the task done, and you actively follow through, then you've stopped your procrastination cycle. Overcoming indecision is a key part of this positive change process, and you'll learn how to get off the fence and follow through with what is important for you to do.

The fourth-century Chinese general Sun Tzu stated that if you know your enemy and yourself, there is no need to fear the results of 100 battles. Sun Tzu's statement refers to decision making as well as to war. If you know why you put off major decisions, know how to make reasoned ones that work for you, and then persist in following through, you've ended procrastination. That won't happen 100 percent of the time, any more than winning all battles is a realistic option. However, you can load the dice in your favor, and you can learn to do that here.

Decision making is an ongoing part of being human. What makes for a good decision? How do you get to that point? Unfortunately, there are no guaranteed guidelines on how to make decisions. Decision-making situations vary widely. Different situations

may require you to apply different values, rules, or procedures. Some decisions involve resolving conflicts. Others contain opportunities, but also risks and uncertainties. The options you face can include tough choices. You may have unwanted trade-offs and lesser-of-evils choices. You may experience conflict between giving up a great opportunity that's out of reach and choosing one that is attainable, but of lesser value. An ideology or bias can influence the direction of the decision unfavorably. Knowing yourself, then, is important in decision making.

How do you improve the quality and timeliness of your decisions when procrastination interferes? In this two-stage process, you learn to get out of a decision-making procrastination holding pattern and act to make and execute purposeful and productive decisions.

To advance this two-stage process, I organized this chapter into three parts. The first describes factors that are involved in indecision. The second is about ending decision-making procrastination. The third discusses how to make and carry out productive decisions.

The Latin word

decido

is the root of

decision

. It has two meanings: to decide, and also to fall off. To avoid a fall, you may decide not to decide. However, if you've adopted the no-failure plan from earlier in this book, and you emphasize discovery over blame avoidance, “falling” like an autumn leave is not an option.

In this section, let's look at uncertainty as a condition for indecisiveness. It discusses four ways to overcome decision-making procrastination, avoid needless pain from sitting on a spiked fence, and act to secure useful gains.

In ambiguous situations you don't see the full picture. You are aware that you face unknowns. You have no guarantee of success regardless of what you do. When you feel unsure and doubtful,

you may avoid making a decision even when managing the uncertainty is a pressing priority.

Uncertainty may stimulate doubts, challenge, or something in between. However, is a high-priority situation with unknowns automatically a cause for stress and procrastination? It depends on how you define the situation and your tolerance for uncertainty.

If you are among the millions who are intolerant of uncertainty, you may find this intolerance rooted in a highly evaluative process. For example, oversensitivity to discomfort plus either exaggerating and dramatizing the dreadfulness of the situation or seeing it as being as bad as, if not worse than, it can possibly be amplifies the tension. Under these amplified stress conditions, it is understandable that a procrastination path of least resistance can seem appealing.

Let's look at four conditions associated with intolerance for uncertainty and procrastination: illusions, heuristics, worry, and equivocation.

Your intuition, insightfulness, and emotional sensitivity were present before your reason developed. The evolution of reason and foresight opened opportunities to go beyond survival to higher-level choices and decisions. However, a tool that is an asset can also be a liability.