Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (24 page)

Read Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 Online

Authors: Gordon S. Wood

Tags: ##genre

The Yazoo land sale was a barefaced assertion of state sovereignty that undermined both the treaty with the Creeks and the federal government’s claim to exercise sole authority over Indian affairs. Indeed, the administration’s high-minded Indian policy was in shambles. Although the policy had the advantage of easing the consciences of those who supported it, it was totally out of touch with the realities on the Western frontier. White settlers in the West had no intention of accommodating the Indians, and they continued to push westward by the tens of thousands. As hostilities with the native peoples became increasingly fierce, the settlers called on the federal government for protection. Washington realized that unless the government stepped in with military force to stop the indiscriminate raiding and counter-raiding by whites and Indians, the entire West, especially the Northwest, would erupt in a general Indian war.

The army had been involved in the Northwest from the beginning; indeed, it alone represented the authority of the United States government in the West during the 1780s. Under the command of Josiah Harmar of Pennsylvania, troops had been sent to the area to build forts and drive off squatters with the hope of avoiding hostilities with the Indians. But in 1790 continued pressure from settlers finally compelled the federal government to authorize a presumably limited punitive expedition against some of the renegade Indians northwest of the Ohio. General Harmar led a force of some three hundred regulars and twelve hundred militia northward from Fort Washington (present-day Cincinnati) to attack Indian villages in the area of what is now Fort Wayne. Although the Americans burned Miami and Shawnee villages and killed two hundred Indians, they lost an equal number of men and were forced to retreat. This show of force by the United States had proved embarrassing, and the administration was determined not to rely on militia to the same extent again.

This initial failure increased the pressure on the government to try once more to convince the Indians of the futility of resistance. In 1791 General Arthur St. Clair, the territorial governor of the Northwest, led a motley and contentious collection of over fourteen hundred regulars, militia, and levies from Fort Washington against the Miami villages. It took St. Clair over a month to move one hundred miles northward, and on November 4, 1791, he and his troops were surprised and overwhelmed by about a thousand Indians from various tribes commanded by Miami chieftain Little Turtle, one of the most impressive Indian leaders of the period. The Americans suffered nearly a thousand casualties, including over six hundred killed. To mock the Americans’ hunger for their land, the Indians stuffed the dead soldiers’ mouths with soil. Because second-in-command General Richard Butler had once told the Indians that “this country belongs to the United States,” they smashed his skull, cut up his

heart into pieces for every tribe that had participated in the battle, and left his corpse to be eaten by animals. St. Clair’s defeat was the worst the Indians ever inflicted on the U.S. Army in its entire history.

70

This humiliation convinced the administration that partial remedies would no longer work in pacifying the Indians. The government overhauled the War Department, doubled the military budget, and created the professional standing army of five thousand regulars that many Federalists had long wanted. At the same time, the government sought to negotiate a new treaty with the Indians.

Encouraged by the British in Canada, who wanted a neutral barrier state erected in the Northwest, the Indians refused to accept any white settlements north of the Ohio River, which had been the declared boundary of Quebec in 1774, and the negotiations broke down. The Indians told the American negotiators that all they wanted was “a small part of our once great country. . . . Look back, and review the lands from whence we have been driven to this spot. We can retreat no farther, . . . and we have therefore resolved to leave our bones in this small space to which we are now confined.”

71

The British continued to supply the Indians with food and arms, rebuilt their old Fort Miami near the rapids of the Maumee River, near what is now Toledo in northwest Ohio, and urged the Indians to resist the Americans with force.

In the meantime the U.S. Army had been reorganized, renamed the Legion, and placed under the command of General Anthony Wayne, a former Revolutionary officer. Because Wayne was noted for his impetuosity (“Brave and nothing else,” said Jefferson, the kind of man who might “run his head against a wall where success was both impossible and useless”), his appointment in 1792 was controversial.

72

But “Mad” Anthony Wayne was determined to vindicate President Washington’s faith in him. Over the next two years he trained, disciplined, and inspired his troops and turned them into a battle-ready fighting force. In the summer of 1794 Wayne and his army of two thousand regulars and fifteen hundred Kentucky volunteers moved northward toward the newly constructed British Fort Miami, with instructions from Knox to “dislodge” the British garrison if necessary, but only if “it shall promise complete success.”

73

After repulsing several Indian attacks in June 1794, Wayne’s Legionnaires moved northward and on August 20 soundly defeated a force of over a thousand Indians at Fallen

Timbers, near present-day Toledo. Although Wayne refrained from attacking Fort Miami, he burned and pillaged Indian towns, crops, and British storehouses around the post. The British, unwilling to provoke a war with the United States, did nothing to aid their Indian allies.

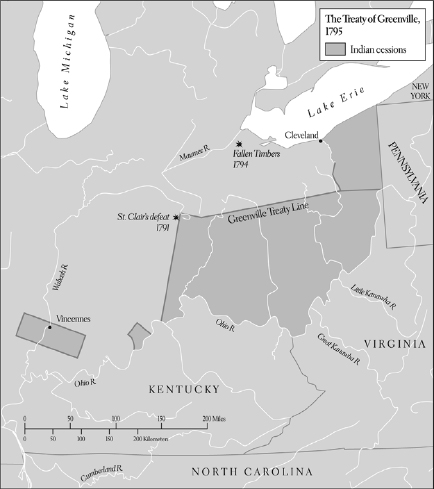

Wayne’s victory broke Indian resistance in the Northwest and destroyed British influence over the Indians, at least until the eve of the War of 1812. The Indians had no alternative but to seek peace, and in August 1795 in the Treaty of Greenville they ceded to the United States their lands in what is now southern and eastern Ohio, together with a strip of southeastern Indiana. Even within the lands the Indians retained, the Americans gained the rights to erect posts and to pass freely. The Indians in the Northwest acknowledged that they were to be dependent on “no other power whatever” except the United States, which the Wyandot Tarhe said they must from now on call “our father.” As children, Tarhe told his fellow Indians, they were to be “obedient to our father; ever listen to him when he speaks to you, and follow his advice.” But of course the father had patriarchal obligations as well: “Should any of your children come to you crying and in distress, have pity on them, and relieve their wants.” By bestowing the name of “father” on the United States, some of the Indians assumed that the Americans were taking on the paternalistic role that the French and British had played. In this respect the Indians were no freer of illusions than America’s white leaders.

74

The outcome at Fallen Timbers made inevitable the British evacuation of the Northwest posts they had been occupying since the Revolution. In the treaty negotiated by John Jay in 1794 and ratified in 1795 Britain finally agreed to get out of American territory. The sending of Jay to England in turn frightened the Spanish with the possibility that the British and the Americans might collaborate to threaten Spanish possessions in the New World. Consequently, Spain suddenly decided to reach a long-delayed agreement with the United States. Washington sent to Spain Thomas Pinckney of South Carolina, who was serving as the American minister to Great Britain. In the treaty that Pinckney signed at San Lorenzo on October 27, 1794, Spain finally recognized American claims to the Florida boundary of the United States at the 31st parallel and to the free navigation of the Mississippi, including the right of Americans to deposit their goods at New Orleans. Both the controversial Jay’s Treaty and Pinckney’s Treaty thus secured the territorial integrity of the United

States in a way the diplomacy of the Confederation had been unable to do. At the same time, the new federal government’s actions strengthened the national loyalties of a region of the country that was intensely localist in outlook and that earlier had flirted with separation from the United States.

The Treaty of Greenville

These achievements were the result in no small measure of the willingness of the Federalist government to create an army in the Northwest and to use it against the Indians. Not only did the U.S. Army’s presence help to defend American settlements in the area, but it also contributed greatly to the process of integrating these Northwestern settlements into

the nation. The army secured American land claims, protected new towns, developed communication and transportation networks, and provided cash and a reliable local market for the settlers’ produce in the Northwest—all in all acting as an effective agent for an expansive new American empire that remained loyal to the national government in the East.

75

That the U.S. Army was not similarly established in the Southwest profoundly affected the different development and loyalties of that region. Although the governor of the Southwest Territory, William Blount, pleaded with the national government for troops to deal with the Creeks and Cherokees, support was minimal. Whereas the Northwest had nearly three thousand regular federal troops by 1794, the Southwest possessed only two U.S. posts with seventy-five soldiers. With federal troops busy trying to put down the Indians in the Northwest, Secretary of War Knox advised Blount to negotiate treaties and pursue a strictly defensive policy toward the Southern Indians. But the settlers kept encroaching on the Indians’ lands, usually in violation of treaties, and the Indians fought back. Settlers in Tennessee like Andrew Jackson were bitter at the federal government’s neglect and its constant harping on the need to negotiate treaties with the Indians. “Treaties,” declared Jackson in 1794, “answer No other Purpose than opening an Easy door for the Indians to pass through to Butcher our citizens.” He warned that unless the federal government gave more aid to the Southwest the region would eventually have to separate “or seek a protection from some other Source than the present.” Even after Tennessee was admitted to the Union in 1796, bitterness against the United States remained.

76

A

NTHONY

W

AYNE HAD TOLD

James Madison as early as 1789 that there was no substitute for military victory in establishing the “Dignity, wealth, and Power” of the United States government, and events since that time had convinced many Federalists that Wayne was absolutely right. If only the United States had defeated the Indians earlier, said Judge Rufus Putnam in August 1794, it “would have given a weight and dignity to the Federal Government that would have tended to check the licentiousness and opposition to Government unfavorable in this

country.”

77

It might even have prevented the events that became known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

In 1794 angry farmers in four counties of western Pennsylvania defied a federal excise tax on whiskey, terrorized the excise officers, robbed the mail, and closed the federal courts. Before everything was over, not only had some seven thousand western Pennsylvanians marched against the town of Pittsburgh and threatened its residents and the federal arsenal there, but rioting against the excise tax on whiskey had spread to the back-countries of Virginia and Maryland.

This so-called Whiskey Rebellion was the most serious domestic crisis the Washington administration had to face. It came at a frightening time. With the French Revolution creating havoc all over Europe and even threatening to spread to America, the Federalists came to fear that this insurrection in the West might actually lead to the overturning of America’s government and the destruction of the Union. Although it was the largest incident of armed resistance to federal authority between the adoption of the Constitution and the Civil War, it was not the only such incident of rural insurgency; indeed, in the two decades following the Revolution the backcountry of states up and down the continent repeatedly erupted in protest, usually over shortages of money and credit among commercially minded farmers who needed both in order to carry on trade.

78

The immediate sources of the uprising of 1794 lay in the decision of the Washington administration in 1790 to levy an excise tax on spirits distilled within the United States. Hamilton calculated that duties on foreign imports alone would not be sufficient to cover the revenue needs of his financial program and that some sort of additional tax would be necessary. The Constitution granted the federal government the authority to levy excise taxes, but many Americans bitterly resented such internal taxes, especially one levied by a far-removed central government. Customs duties were one thing; excise taxes were quite another. Customs duties were indirect taxes, paid at the ports on imported goods, often on luxuries. Most consumers were scarcely aware they were paying such taxes, blended as they were in the price of the goods. But payers of excise taxes knew only too well the burden of the tax. British on both sides of the

Atlantic had long resisted what the Continental Congress in 1775 called “the most odious of taxes.”

79