Duke (60 page)

Authors: Terry Teachout

Ellington used the interval between the San Francisco and New York performances to revise the concert, changing its running order and composing a new instrumental prelude that fused the opening numbers into a single twenty-minute musical sequence called “In the Beginning God.” The prelude is one of his most majestic utterances, a six-note theme based on the first four words of the King James Bible that is intoned by Harry Carney as if it had been chiseled out of granite. Unlike most of Ellington’s themes, the “In the Beginning God” motif is beautifully suited to symphonic development, and its placement at the very beginning of the piece creates expectations that he fails to fulfill. Instead of spinning out the theme at appropriate length, he follows it with a string of tenuously related, variably inspired musical events. First comes a part-spoken, part-sung bass-baritone solo that describes the primordial chaos (“No symphony, no jive, no

Gemini V

”) preceding the moment of creation. Then a choir shouts the names of the books of the Bible, followed by a drum solo from Louis Bellson (who had briefly replaced Sam Woodyard) that is capped with an anticlimactic coda. Not only does this miscellaneous-sounding assemblage fail to gel into a musical whole, but the hipsterisms of Ellington’s text sit uneasily alongside the magisterial sound of Carney’s saxophone.

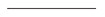

“You can’t jive with the Almighty”: Rehearsing

A Concert of Sacred Music

at Coventry Cathedral, 1966. Ellington’s first venture into the field of religious music ranked high among the triumphs of his later years—but some black ministers questioned whether so worldly a musician had any business playing in churches

The concert continues with an anodyne gospel waltz called “Tell Me It’s the Truth,” an extended “Come Sunday” sequence, and two dullish vocal numbers from

My People,

“Will You Be There” and “Ain’t but the One,” after which Ellington plays

New World A-Coming

. The grand finale, also drawn from

My People,

is a long-meter choral version of “Come Sunday” called “David Danced Before the Lord with All His Might” (the reference is to 2 Samuel 6:14) in which Bunny Briggs performs a lengthy tap dance before the altar. The inspiration for Briggs’s inclusion in the program, Ellington explained, was the medieval legend of the juggler of Notre Dame: “It has been said once that a man, who could not play the organ or any of the instruments of the symphony, accompanied his worship by juggling. He was not the world’s best juggler but it was the one thing he did best. And so it was accepted by God.” The inclusion of the dance was a stroke of theatrical genius, the one moment in which Ellington acknowledged the essentially theatrical nature of the concert without violating its spiritual purpose.

The New York reviews, unlike those of the San Francisco premiere, were all over the map. Alan Rich described the concert as “vintage Ellington . . . properly elemental, sometimes brutal, never less than compelling” in the

New York Herald Tribune

. John S. Wilson of

The New York Times

was a tougher nut to crack: “Mr. Ellington moved carefully in his unfamiliar surroundings. . . . Altogether, there was less of the true Ellington stamp on this concert than one would have hoped for.” The truth lies somewhere between these extremes. Over and above its inconsistent musical merits, the First Sacred Concert, as it is now known, comes across today as a period piece, as dated as the jazz, folk, and rock masses that were all the rage in “progressive” churches of the sixties and seventies. Still, Ellington’s revisions had significantly strengthened the total effect of the concert, and he would perform it many times in the next few years, usually to great public acclaim.

***********

For the most part the concert was accepted as a testament of personal faith. Ed Sullivan, whose sense of mass taste was unerring, brought Briggs and the band onto his Sunday-evening program to perform “David Danced Before the Lord,” while

Ebony

praised the New York premiere: “A type of music once disdained as being fit only for bars and bordellos was being performed in a sacred concert by a man who had helped earn for it the greatest respect.” But the rest of the black community was of two minds, and the black ministers of Ellington’s hometown were disinclined to look kindly on the First Sacred Concert when it was presented a year later at Washington’s Constitution Hall. The Baptist Ministers Conference, which consisted of the leaders of some one hundred and fifty Washington-area churches, voted not to endorse the concert, and several members refused to allow tickets for the event to be sold in their churches. One of them told

The

Washington Post,

“Duke Ellington represents the type of service that we as Baptist ministers didn’t feel represented the Christian impact,” while another said that Ellington’s own life was “opposed to what the church stands for,” mentioning his “nightclub playing and the fact the music is just considered worldly.” These views were widely shared among religiously conservative blacks. Even Joya Sherrill, a Jehovah’s Witness, preferred not to take part in the San Francisco premiere, telling Ellington that she thought it inappropriate to play jazz in a church.

A month after the First Sacred Concert was performed in Washington, Edna Ellington died of cancer. By then the band was in Italy, where her long-estranged husband issued a tactful statement: “She loved life. She was a woman of virtue and beauty. She would never lie. God bless her.” Her passing gave Evie brief hope that Ellington would marry her, but he preferred not to. In Mercer’s words:

Evie absolutely expected to become Mrs. Ellington, but I think Pop just came right out and said, “No, we’re not getting married!” There was no pressure being put on him from any other direction so far as I was aware . . . somehow he didn’t want to do it, and I think the main influence against it may have been his sister, Ruth, because she had become as possessive of him as he of her.

It seems more likely, however, that at the age of sixty-seven, Ellington had no wish to upset his life by altering the status of any of his relationships—not even with the Countess, whom he had previously told that he was legally married to Evie. He still wanted everybody in the palm of his hand, where they had been for the whole of his adult life. Yet one member of his extended family had long been reluctant to cooperate fully with Ellington’s wishes, and a few months later he would thwart them once and for all.

• • •

By 1964, if not before, Billy Strayhorn was an alcoholic. “He had his good days, but he had his bad days, believe me, the poor thing,” a close friend recalled. “He was drinking day and night. Half the time, he wasn’t really there.” Strayhorn’s relationship with Aaron Bridgers had trailed off after Bridgers moved to Paris in 1947 to pursue his own musical career, and since then Strayhorn had been unable to find a suitable romantic partner. Nor was his later work for Ellington gratifying, consisting as it mainly did of arranging the latest pop tunes. Strayhorn put the best possible face on it: “It’s more a matter of morality than technique. . . . If I’m working on a tune, I don’t want to

think

it’s bad. It’s just a tune, and I have to work with it. It’s not a matter of whether it’s good or bad.” Mostly, though, the tunes were bad, or at least inappropriate to his talents. He continued to contribute to the suites, but not as frequently, and except for a single solo album released in 1961, he had less and less to say.

Early in 1964 Arthur Logan, Ellington’s doctor, noticed that Strayhorn was short of breath and suggested that he undergo a thorough physical examination at once. A few days later he told Strayhorn that he had cancer of the esophagus, the result of a lifetime of drinking and smoking, and that it was terminal. Ellington was appalled by the diagnosis, but Strayhorn appears to have accepted it with a typical mixture of stoicism and irony. During a visit to the Logans’ brownstone, he plucked a wax apple out of a lazy Susan and looked at it. “A fruit that only looks like it’s alive,” he said. “That makes two of us.” In 1965 he underwent a tracheostomy, followed by a debilitating course of radiation therapy. Then came a gastrostomy and the removal of his esophagus. Even then he continued to drink, pouring alcohol directly into his feeding tube.

By that time the rest of the world was figuring out what Ellington had always known, which was that Strayhorn, far from being the older man’s epigone, was a giant in his own right. In June of 1965, shortly before he went under the knife, he gave his first and only solo concert at New York’s New School for Music. John S. Wilson took note of the event by writing a profile for

The

New York Times

—the one occasion during his lifetime when he was so honored outside the jazz press—in which he explained, mildly but firmly, that his collaboration with Ellington had endured because the older man didn’t tell him “what to write or how to write.” But it was too little, too late. Strayhorn turned up at the New York premiere of the First Sacred Concert, accompanying his beloved Lena Horne in a song. It was, so far as is known, his last public appearance.

He began to disintegrate shortly afterward, finishing only two more compositions for the Ellington band. The second of them, which he called “Blood Count,” was a feature for Johnny Hodges, his favorite soloist, whose contorted melodic line was the musical equivalent of a howl of pain. “He wrote his epitaph and then had Rabbit play it,” said Otto Hardwick when he first heard “Blood Count.” After that he waited for death. Ellington called him on the phone each day but never visited, unable to bear the thought of seeing what cancer had done to his friend. The end came early in the morning of May 31, 1967. The band was playing in Reno, and Arthur Logan called Ellington to break the news. “Are you going to be all right?” Logan asked. “Fuck no, I’m not going to be all right!” he replied. “Nothing is all right now.” Then he wept. “After I hung up the phone I started sniffling and whimpering, crying, banging my head up against the wall, and talking to myself about the virtues of Billy Strayhorn,” he recalled. “Why Billy Strayhorn, I asked? Why? Subconsciously, I sat down and started writing what I was thinking, and as I got deeper and deeper into thinking about my favorite human being, I realized that I was not crying any more.”

A week later, the elegy that Ellington wrote that morning was delivered for him at Strayhorn’s funeral, which took place at St. Peter’s Church in New York. “Duke was sitting by himself, frozen, immobile, staring straight ahead, not seeing, hearing or recognizing anything or anybody,” Don George remembered. So heartbroken that he did not trust himself to be able to get through the elegy without breaking down, Ellington sat in stony silence as his heartfelt words were read out loud to the mourners:

William Thomas Strayhorn, the biggest human being who ever lived, a man with the greatest courage, the most majestic artistic stature . . . demanded freedom of expression and lived in what we consider the most important and moral of freedoms: freedom from hate, unconditionally; freedom from self-pity (even throughout all the pain and bad news); freedom from fear of possibly doing something that might help another more than it might himself; and freedom from the kind of pride that could make a man feel he was better than his brother or neighbor.

After twenty-eight years, their stormy voyage together on the sea of expectancy was over.

16

“THAT BIG YAWNING VOID”