Dreaming in Hindi

Authors: Katherine Russell Rich

7. "My car is stuck (in the mud/in the ditch)"

8. "I am leaving by the early train"

9. "Birds of the same feather fly together"

10. "The matter is not one for laughing"

12. "This is a major problem and cannot be disposed of so easily"

13. "After a long time, I have the honor to see you"

14. "I can understand you quite well now"

15. "You will be taught. He will be taught. They will be taught."

16. "If a change takes place, we shall inform you by cable"

18. "It is late; let us go home"

19. "You go on; we are coming"

The Cruel Festival Time by Nand Chaturvedi

Copyright © 2009 by Katherine Russell Rich

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rich, Katherine Russell.

Dreaming in Hindi : coming awake in another language /

Katherine Russell Rich

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN

978-0-618-15545-3

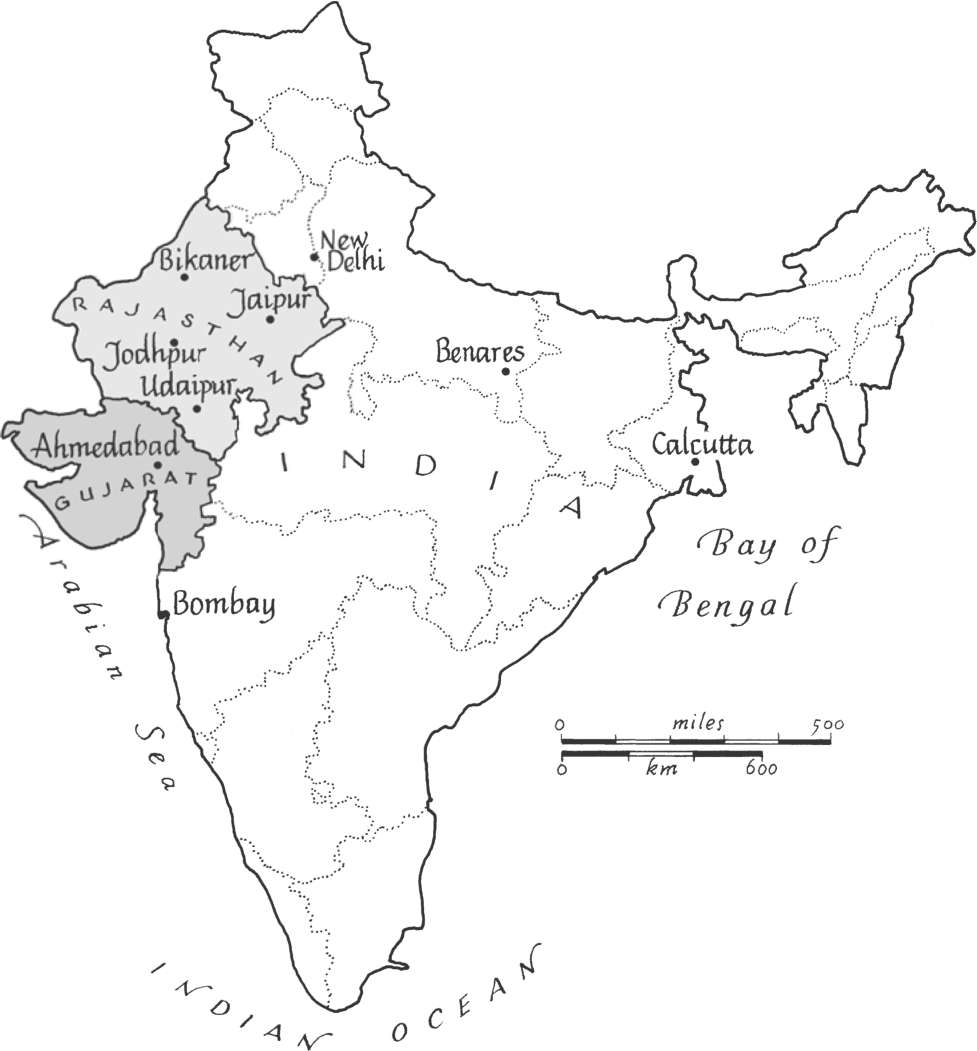

1. IndiaâDescription and travel. 2. Udaipur (Rajasthan, India)â

Description and travel. 3. Rich, Katherine RussellâTravelâIndia.

4. AmericansâTravelâIndia. 5. Hindi languageâSocial aspects.

6. Hindi languageâPsychological aspects. 7. Psycholinguisticsâ

Case studies. 8. IndiaâSocial life and customs. 9. Udaipur (Rajasthan,

India)âSocial life and customs. I. Title.

DS

414.2.

R

53 2009 954.05'31092âdc22 2008053295

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Victoria Hartman

DOC

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The author gratefully acknowledges permission to use the poem

"The Cruel Festival Time" by Nand Chaturvedi.

Stuart Paddock Rich, in memoriam

One time in India, I appeared half-naked in a temple, just up and flashed the worshipers. This was not something I'd been planning to do; I surprised myself on the Lord God Shiva's birthday. Surprised the celebrants, too, I'd say. They hadn't been expecting it either.

This would have been a long time in, for by then I could make out what the people around me were saying. I knew, for example, what the woman in a coppery sari had squeaked to the man pressed between us on the bus ride up to the temple town. "

Gori! Gori!

" she'd exclaimed: "Look! A white woman!" The main reason I'd come to India, in fact, had been to learn the language. Originally, I'd thought that if I could, it would be like cracking a strange veiled code, a shimmering triumphant entry, but by now all it was was someone talking.

By the time of that trip, I knew a lot of things easily: That the peeling dashboard sticker of a goddess on a tiger meant the bus driver was a devotee of the goddess Durga, for instance. Or what the Hindi was for "

The langur has no tail due to an electrical accident,

" one of the things a man in Western clothes, an engineer, said when we struck up a conversation outside the town's main temple.

"

There used to be beautiful gardens here,

" he said. "

The Palace of the Winds at the top of the hill was once the summer residence of kings. Would you like to join us for Shiva's birthday worship?

"

*

Not one word jammed, the talk was purling, though every so often the man would excuse himself and slip into the temple, then reemerge. The last time he did, he was in a bright red lungi wrap, transformed from an engineer. A grizzled old man in a white lungi followed him.

"

You may join us, but you must change your clothes. We don't allow pants inside,

" the old man, a pandit, a Brahmin priest, said. I said I'd be honored to be included.

"

See, Pandit-ji! She speaks good Hindi,

" the engineer said, and the priest handed me a bundled white cloth, the makings of an impromptu sari. I eyed it warily. Anytime I'd tried to wrap myself, the results had been unfortunate.

He directed me over a high step, into a sanctum containing statues of gods, where five men and a woman with grape green eyes were seated in a circle. Farther on, in a back room, I gave the cloth a try. I took off my jeans and draped myself, I thought, rakishly. But when I reappeared at the door, the Venus de Milo effect unraveled into strips, leaving my

gori

flanks exposed. The men gaped. The green-eyed woman barked out a reproof. Western women were known to flagrantly exhibit themselves. The pandit abruptly ordered me out of the room, commanded the woman to follow and lend a hand.

I worried I'd irrevocably disgraced myself, but once she'd snugly fitted me, the priest waved me back to the circle. He was solicitous throughout the ceremony, through the hours we kneeled on the cold stone floor and my knees turned to points of stabbing pain. He guided my hands onto copper bowls, onto my neighbors, at the necessary moments. We washed the gods in milk, honey, curds, water, and ghee. He continually chanted their names, and I blinked to find myself sinking into what seemed like a far center I'd always known. This place was greenly translucent, soothing, universal, like the water in the pool where as a child I'd nearly drowned and hadn't, till I surfaced, been afraid. But the sudden merger with the infinite skewered my earthly activities. Lulled, I tipped a bowl of water onto a deity's head.

"

Dhire! Dhire!

" the devotees cried: "Slowly! Slowly!" "

We are giving the god a bath.

"

Incense spiraled up like djinns. We rubbed the gods with sugar. We garlanded them with marigolds, as people gathered on the steps outside. They leaned across the stone threshold to the temple and peered in. The gawkers lit more sandalwood sticks, left oranges as offerings, asked what was going on in there. There was a foreigner?

"

Her Hindi is good,

" the devotees informed them the first hour.

"

Her Hindi is very good,

" the devotees said in the second, though my known repertoire had not expanded much beyond "

What was that?

"

The third hour, a new man joined us, glanced over, said something. "

Haan,

" the priest said: Yes. "

She is fluent.

"

"

That was Sanskrit he was speaking!

" the devotees exclaimed after each of the priest's rumbled chants. "

Very old,

" the priest concurred, holding up a text the size and shape of a comic book, breaking to provide me with some tutelage in the classics. Then the green-eyed woman produced small outfits hemmed in tinsel, and we carefully dressed the gods.

Afterward, with the grainy smell of ghee in our hair, the worshipers clamored to explain that the ceremony was older than Buddhism, than Jainism, than Christianity. "

It is only once a year,

" a man said, adding that I was lucky to have arrived here on this day. "

And after, you feel so peaceful,

" another man said of the four hours of pure devotion. "

By doing this, you keep the world happy,

" he told me, though the exact verb he used was more like "set."

What follows is a story about setting the world happy, about the strange, snaking course devotion can take. It's about what happens if you allow yourself to get swept away by a passion. The short answer is this: inevitably, at some point, you come unwrapped.

It's a story about a stretch of time I spent in India, learning to speak another language. Since that year was an exceptionally violent and fragmenting one, both in India and throughout the world, it's a story that sometimes turns savage. This book, the way I'd conceived it before I left, was going to be solely about the near-mystical and transformative powers of language: the way that words, with only the tensile strength of breath, can tug you out of one world and land you in the center of another. By the end of that year, however, the story was still about transformation, yes, but it had become one about the destructive power of words as wellâthe way they can reshape people, can leave them twisted, can break them. It's about language as passport and as block.

Since the book is concerned with language, with one person's attempts to learn another, and since the person in question, i.e., me, is not a blazing talent in that department, I think I should probably allow this right up front. I'm not that great, naturally, at learning other tongues. I simply love the process. When my mother traveled, she liked to eat her way through a place. Her trip journals were all about meals, never sights:

Got up at eight. Went to the French Quarter for beignets. At eleven had shrimp remoulade at Christian's.

"I speak menu," she'd say. Me, when I travel, I just want to speak. I've always been fascinated by language in any form, the more unintelligible, the better. When I get on a plane, I lose myself in the vocabulary section of the guidebook, not excluding the sentences for businessmen. I can cite favorite lines from various books. "

Is vakt sattewalon ne is chiz par kabza kar liya hai,

" from the

Cambridge Self Hindi Teacher,

is a good one: "Speculators have for the moment seized on this article."

Cambridge

stands out because it breaks form, which requires that the travelers' sentences be kept jaunty. It allows a measure of melancholy, even existentialism. "Unfortunately they are in such a bad condition we can't accept them." "The date of the arrival does not matter much." This is a quality that I think sets it apart, though others might argue.

I love a lot of things about language studyâthe way it can make you feel like a spy, the covert glimpses it provides into worlds that were previously off-limits, even the confounding difficulties, the tests it puts you to. For the purposes of this book, I interviewed a former Fulbright scholar, a linguist named A. L. Becker, who knows Burmese, Thai, Old Javanese, and Malay well enough to teach them. "I sometimes think I study these things," he said, "because I have such a hard time with it," and I nodded emphatically. Also for this book, I interviewed a number of neurolinguists and people who study the science of language acquisition, for at the same time that I developed a passion for Hindi, a corresponding obsession kicked in: to understand what learning a second language does to the brain. The process, for me, was frustrating and exhilarating and at times transcendent, all in a way that felt deeply corporeal; I could only believe it was scrambling my brains. What I learned was that to some extent, a second language does. It makes you not quite yourself, your old one.

This might explain the pattern I observed when I first began taking Hindi lessons. People would exclaim, "My daughter's doing that! She was having trouble at Smith and had to drop out for a semester, and so she's decided to study Mandarin!" Someone had retired and was learning Basque in a chatroom. Another, recovering from a breakup, was hot in pursuit of Greek. Conjugants, I began to think of us as. I'm sorry to have to report to the Modern Language Association that in monolingual America, no one much past school age seems to take up a language when their lives are going gangbusters, that it's a preoccupation of the disoriented. I've a feeling the same principle might apply to any pursuit that demands you start over as a beginner, given all the other stories I've heardâof the divorces and dislocations that resulted in people learning, finally, how to swim, or play chess, or play the piano. Mandarin, mandolinâin a way, same thing. You embrace pursuits like these as an adult, I think, as a transfer of focus when your life has shifted you into another place, when you've had to begin again in some way. By immersing yourself as a neophyte in a realm that's more controllable than your now unwieldy and sorry whole existence, you keep yourself in one piece, at least in this one area. The impulse is probably a perverted survival mechanism, but so what?