Double Victory (17 page)

Authors: Cheryl Mullenbach

Sammie Rice was one of the nurses who contracted malaria while in Liberia. She recovered and was with the group that went to England in 1944. Sammie continued to send part of her army paycheck back home to her family as she had while in Liberia. They knew they could count on her. And the wounded servicemen whom the nurses cared for in the hospitals around the globe felt only gratitude for the black “angels of mercy.”

There's a War Very Near

Birdie Brown was six feet tall, and people looked up to her. But it wasn't because of her height that her fellow nurses looked up to Birdie. It was because they were the first group of black army nurses in the Pacific theater of operations, and Birdie was their leader. She was the chief nurse of the 268th Station Hospital unit. Part of her duties included helping the nurses adjust to life in a war zone.

Their adjustment started with their voyage from the United States. All but two of the nurses had suffered from seasickness. Louise Miller, Elcena Townscent, Marjorie Mayers, Prudence Burns, Claudia Mathews, Thelma Fisher, Beulah Baldwin, Dorothy Branker, Joan Hamilton, Bessie Evans, Alberta Smith, Inez Holmes, Elnora Jones, and Geneva Culpepper arrived in

Australia in December 1943. The

Pittsburgh Courier

reported that “bedlam broke loose” among the troops at the sight of the black nurses and “the nurses received an ovation that befitted a procession of queens.”

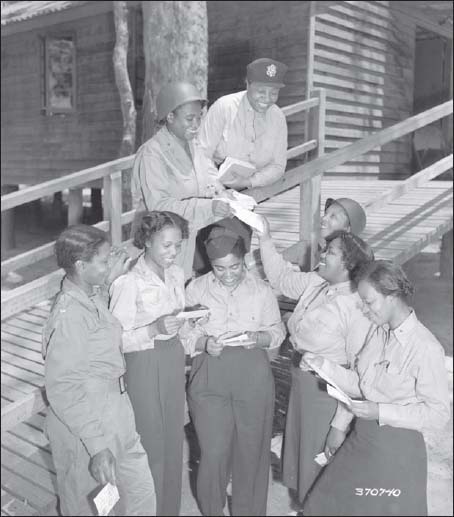

Lts. Prudence L. Burns, Inez Holmes, and Birdie E. Brown arrive at the 268th Station Hospital in Australia and receive their first batch of mail from home, November 1943.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WW II List #187

The nurses would stay at a staging area for nurses until they received orders sending them to other military hospitals in the Pacific. At the military camp in Australia they learned how to live under GI combat conditions. That included exercising in helmets and combat uniforms.

By spring 1944 the nurses felt impatient to move to their next assignment “somewhere in the southwest Pacific.” Birdie summed it up: “We are extremely anxious to get to work. We have enjoyed Australia's hospitality and made lots of friends but we can never get out of our minds the fact that there's a war very near us and we're here to do a job. We shall be happy when we are working.”

The nurses did move on to other areas of the war zone. They went to a 250-bed hospital in New Guinea, where Prudence Burns became head surgical nurse. Geneva Culpepper was assigned under her as a surgical nurse. Joan Hamilton was a dietitian. Marjorie Mayers was in charge of recreation at the hospital, which included the enlisted men's basketball team.

Army nurses waiting for assignments to hospitals in the Southwest Pacific stretch their muscles in an early-morning workout at a training camp in Australia, February 1944.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WWII List #183

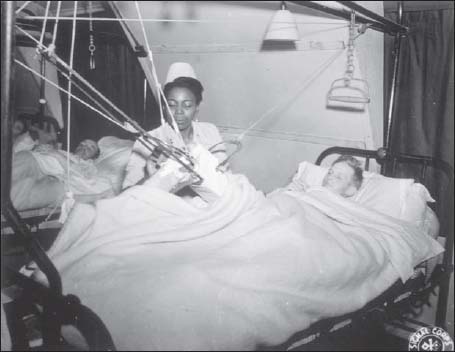

Left to right: 2nd Lt. Prudence Burns, 2nd Lt. Elcena Townscent, and an unidentified nurse care for Sgt. Lawrence McKreever at the 268th Station Hospital in New Guinea, June 1944.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WW II List #142

At one point during the 268th's time in the Pacific, a US newspaper reported that Birdie and some of her nurses had been captured by the enemy. The report was inaccurate. But when a journalist found Birdie at work in New Guinea and told her about the published article, Birdie had a good laugh. She wanted to assure readers back home that she was very much “uncaptured” and was looking forward to returning to America at the end of the war.

But it wasn't quite time for the nurses of the 268th to leave the Pacific theater of operations for home. The American armed

forces had liberated the Philippines from the Japanese in the summer of 1945. The nurses of 268th were needed there. So off they went for one last assignment. While they were in the Philippines the war ended with the bombing of Japan by the United States in August 1945. By October 1945 the nurses' bags were packed, and they were waiting for orders to return home to the United States. But before leaving the Philippines, one of the nurses had one more duty to perform.

Prudence Burns wanted to marry her fiancé, Sgt. Lowell Burrell, who was stationed in the Philippines too. So just before leaving for the United States, Prudence and Lowell were married. Prudence wore a wedding dress designed by one of her friends. It was fashioned from the most luxurious fabric they could find in the war-torn islandsâsilk from a military parachute.

The America We Live In

Louise Miller had trained with the 268th Station Hospital nurses at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, and she had been with them in Australia and New Guinea. She didn't go to the Philippines with the rest of her unit. In the spring of 1945, Louise received word that her father was sick back home in Atlanta, Georgia. The army sent her back to the United States so she could spend some time with him.

Louise wore her Army Nurse Corps uniform on her long flights home. She passed through Tucson, Arizona, and then went on to her next stopâDallas, Texas. Louise was tired and worried about her father. She was also hungry. As soon as she arrived in Dallas, she headed to the nearest coffee shop for a bite to eat. She had plenty of timeâthere was a three-hour layover. She approached the counter, where she was told she could eatâbut only in the back of the shop.

Louise's Army Nurse Corps uniform had not impressed the coffee shop worker, and it didn't mean anything to a passenger on the plane she boarded for her flight to Atlanta. She had just settled into her seat on the plane when the flight attendant asked her to move to another seatâthe white passenger Louise had sat next to didn't want to sit next to her. Louise was saddened by this harsh welcome back to the United States after her years of service to the country. She predicted, “Our boys will not be willing to come back to the America we live in when victory is won.” She felt other returning black veterans would be disappointed that their service to the country in time of need was not appreciated.

Black Nurses in Europe

The first contingent of black army nurses assigned to Europe arrived in August 1944. Captain Mary L. Petty led her unit of 63 nurses as they walked down the gangplank of the ship that had brought them to England. The women knew they had a critical role to play in Europe. Because they were nurses they were committed to caring for the wounded soldiers. But they had another important task ahead. In a ceremony as they disembarked the ship, Captain Petty spoke about the nurses' roles. She said the contingent of black nurses had “come to foreign soil to render the greatest possible service in this theater and to do everything within its power to improve race relations.”

Some of the nurses who had served in Liberiaâincluding Thelma Calloway, Idell Webb, Sammie Rice, and Roby Gillâwere with the unit that arrived in England. The nurses expected to serve in hospitals in Great Britain and France. And they knew they would treat both black and white soldiers. Black nurses touching wounded white soldiers had been a problem in some American hospitals.

Black army nurses line the rail of their vessel as it pulls into port, and wait to disembark as the gangplank is lowered to the dock in Greenock, Scotland, August 1944.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in WW II List #141

“When we first entered service in Camp Livingston, Louisiana, we were forbidden to touch white soldiers,” Dorcas Taylor remarked. “But before we embarked for Britain, they needed us so badly, we touched everybody.”

The army nurses who comprised the first unit of black nurses in Europe did not receive the most prized assignment. They had been sent to England to relieve a unit of white nurses who had been caring for Nazi prisoners of war. It was not a duty most American nurses cherished. While it was the responsibility of all nurses to tend to the wounded and help them recover, it was difficult to show compassion for the very men who had wounded and even killed American soldiers. And some black citizens in America believed that the black nurses had been assigned to prisoner of war hospitals intentionallyâto keep them from serving in hospitals where they would treat white American soldiers.

First black nurses in England, 1944.

National Park Service; Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site; National Archives for Black Women's History/Photo by US Army Signal Corps

After a few months, the army decided to change the assignment of the black nurses. Rather than holding the prisoners in hospitals staffed only with black nurses, the prisoners were transferred to other installations. The nurses continued to serve in England and Franceâbut they cared for American soldiers.