Double Victory (16 page)

Authors: Cheryl Mullenbach

Lt.(jg.) Harriet Ida Pickens and Ens. Frances Wills, the first black Navy Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) to be commissioned, were members of the final graduating class at Naval Reserve Midshipmen's School in Northampton, Massachusetts, December 1944.

National Archives, AFRO/AM in

WW

II List #159

Other branches of the military were even slower in allowing black women to join. The women's branch of the Coast GuardâSemper Paratus, Always Ready (SPAR)âadmitted black women in March 1945, and only five blacks served in the SPAR during World War II. The Marine Corps had allowed white women to join and serve since 1913âbut only during wartime. The women who served during World War II were discharged when the war ended. Black women were not admitted to the Marine Corps during the World War II years.

That's History

When Sammie M. Rice learned she would be going overseas with the US Army, she knew it would be a milestone in her life. But she also understood what it meant for

all

black women. Sammie wrote a friend, “We will be the first group of Negro nurses to go overseas during war. That's history, you know. Everybody is excited.”

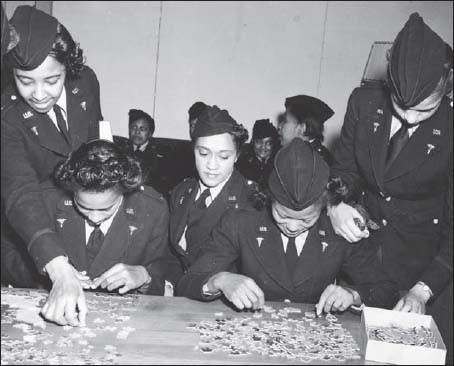

Black US Army nurses. Sammie M. Rice is the first on the right.

Sammie Rice Collection WVO257, Betty H. Carter Women Veterans Historical Project; Martha Hodges Special Collections and University Archives; University Libraries, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, North Carolina

Before shipping out Sammie spent two weeks at Camp Kilmer in New Jersey. Even this was top secret. She could write letters to family and friends, but she was not allowed to disclose her location. And she and the other nurses were forbidden to leave the camp as they prepared for their overseas assignment.

Sammie didn't know

where

she was going; but she knew she would be traveling by ship, and she knew that could be dangerous. Traveling by ship in the waters of the Atlantic meant the possibility of torpedo attack by German submarines. But Sammie was comforted by the fact that the ship would be accompanied by an American convoy all the way to their destination.

Sammie was part of a unit of black army nurses who left America on the USS

James Parker

at 6 am on February 7, 1943. One of the nursesâThelma Calloway from Montclair, New Jerseyâwrote a song about the ship titled “James Parker Blues.” She sang the song in the ship's dining salon many times during the month-long voyage. The trek across the Atlantic was accomplished without interference from the Germans. The only misfortune occurred when Ellen Robinson, Sarah Thomas, and Esther Stewart contracted the mumps. And Sammie Rice suffered from seasickness throughout the trip.

The US Navy transport USS

James Parker. Courtesy of US Naval Institute

Black US Army nurses serving in Liberia.

American Foreign Service Journal photo from US Office of War Information, AFRO/AM in WWII List #153

The USS

James Parker

delivered the army nurses safely to Casablanca, French Morocco, on March 10. The nurses spent several days on “shore leave” enjoying the sites of the beautiful city. They spent time at the Red Cross club and attended a dance held in their honor by American military officers. From Casablanca the nurses set out for Dakar, French West Africa (now Senegal). After a brief stay, they journeyed on to Freetown, British West Africa (now Sierra Leone). Finally, they reached their

destinationâthe 25th Station Hospital in Liberia on the west coast of Africa.

One of the nurses, Alma Favors from Chicago, expected to miss her family while she was overseas. But her homesickness was lessened a little when she ran into one of her cousins thousands of miles from home. Staff Sergeant Paul Favors from Detroit, Michigan, greeted Alma as she settled into her new home. Back in the States, Paul had been a sparring partner with the famous boxer Joe Louis. But in Liberia, Paul was just one of many American soldiers who had been sent to Africa to guard a precious resource.

American soldiers were stationed in Liberia to protect the large rubber plantations owned by an American company that supplied the Allied military with most of its rubber. American and Allied armies used immense amounts of rubber for tires on vehicles. And with the other major world supplier of rubber under enemy control in Malaysia, the security of the Liberian rubber plantations was crucial. But the risk of contracting various diseases was quite high in Liberia in the 1940s. Clean drinking water was hard to come by, and malaria was widespread. There was a critical need for the army nurses who arrived in Liberia in 1943.

It didn't take long for Sammie Rice and the other army nurses to settle into a routine at their new assignment. The 25th Station Hospital staff treated soldiers with diseases and also American pilots who had been injured in battles on the Italian front. Many of the pilots suffered from burns they had sustained when their planes crashed. Lieutenant Susan E. Freeman was in charge of all the nurses. She quickly assigned nurses to key positions. Sammie Rice began her duties as charge nurse in a ward where she cared for 11 patients who were suffering from psychological problems.

Lts. Roby Gill, Beaumont, Texas; Leola M. Green, Houston, Texas; Mattie L. Aikens, Macon, Georgia; Zola Mae Lang, Chicago, Illinois; and Ellen L. Robinson, Hackensack, New Jersey, were US Army nurses sent to Liberia.

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; The New York Public Library; Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations; US Office of War Information Army Signal Corps

While the nurses were highly regarded for their medical expertise, the Liberian people quickly learned that the nurses had other skills to offer. Jewell Paterson and Idell Webb had brought a supply of vegetable seeds from America. They began to raise corn, tomatoes, and beans and contributed the produce to the army mess. Native Liberian boys helped cultivate the vegetables and began to enjoy the delicious results too. The boys took seeds back to their villages and started their own gardens.

Both the army mess and the local Liberians began to eat better when Idell, fellow nurse Roby Gill, and the local Liberians teamed up to raise a flock of robust chickens that produced a steady supply of fresh eggsâand the occasional chicken dinner. The Liberians supplied the chickens, but when they arrived, the chickens were scrawny and produced small eggs. The American nurses tried to locate some corn to feed the chickens, but none could be found. Instead, the Liberians gave the nurses some native rice. Idell and Roby mixed the rice with bread soaked in water and fed it to the chickens. The chickens gobbled up the unusual concoction. EveryoneâAmericans and Liberiansâwere delighted when their rice-and-bread-fed chickens became chubbier and produced much larger eggs.

When army nurse Eva Boggess from Waco, Texas, wasn't tending patients in the hospital, she could be found looking for African bugs to add to her collection. Chrystalee Maxwell from Los Angeles, California, had bought a secondhand camera and became known as the official photographer. She was also selected by the soldiers as the best dressed nurse in the unit. When Chrystalee wasn't in her nurse uniform, it wasn't unusual to see her in plum-colored slacks and jacket, or fluffy blouses with lace trim, pleated skirts, mesh stockings, and satin shoes. Thelma Calloway, the nurse who had composed and sung “James Parker Blues” on the voyage from the United States, continued to compose and perform. She was working on another piece she called “The Liberia Blues.” It was a song about ocean steamers, sea crossings, and “a yen to be back in America.” All the nurses took pleasure in the unit's two pet monkeysâuntil one of the mischievous little creatures found its way into a nurse's room and ate her lipstick.

The nurses joked about the frequency with which malaria struck in the camp. They even invented a mock African Campaign

Ribbonâmodeled after the authentic medals bestowed on soldiers who had shown courage in battle. The nurses conferred the African Campaign Ribbon to their colleagues who had endured at least one bout with malaria. But many of the nurses were victims of the disease, and it was not really a laughing matter.

The nurses were able to joke about their malaria attacks, but they couldn't find any humor in events that occurred late in 1943. After only nine months in Liberia, the first contingent of black nurses to serve overseas was ordered back to the United States. By December they had all returned home and were reassigned to new posts.

Officials said the return of the black nurses was “only routine” and that there were many letters “on file” commending the nurses for the “splendid” work they had performed in Liberia. Most of the nurses themselves said they didn't know why they had been reassigned. Gertrude Ivory said she and the other nurses were brought back to the United States because they all had malaria.

The Liberian government was enthusiastic about the services the black American nurses had performed. In April 1944 officials from Liberia asked the US government for permission to grant a medal of honor to Lieutenant Susan E. Freeman, the woman who had led the work of the nurses. The Liberians wanted to honor her for “distinguished contributions” to their country. The US War Department approved the request, and Susan was awarded the Liberian Humane Order of African Redemptionâan award that recognized individuals who had performed humanitarian work in Liberia. In addition, Susan Freeman was honored as the 1944 Mary Mahoney Award recipient by the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses. This award honored nurses who had “significantly advanced opportunities in nursing for members of minority groups.”

The black army nurses who had been the first black unit of nurses to serve overseas continued to serve in the Army Nurse Corps at various hospitals around the world. Some were assigned to hospitals in the United States. Several of the nurses who had served in Liberia went to England with a unit of army nurses. Others went to the Southwest Pacific war zone. Rosemary Vinson, Daryle Foister, Fannie Hart, Anna Landrum, and Caroline Schenck were assigned to the China-Burma-India theater of operations.