Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (28 page)

Read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Nonfiction, #Biography, #History

By the time we get home, just before lunch, Dad is in drag. We take off the black Afro wig and put him to bed.

Mum has told the farm laborers she will pay a ten-kwacha bonus to anyone who comes out to plant tobacco. She takes a hip flask of brandy and rides out in the rain (horse steaming saltily under her) to the fields. The laborers are already drunk. They crawl, stagger, supporting each other, singing and damply cheerful out to the field. The crop is planted, but the tobacco is not in straight lines that year.

We are supposed to be holding a proper English Christmas lunch at noon for our houseguests and various neighbors. The electricity is out. Adamson has been passing out beers to anyone who comes up to the back door. He is crouched over a fire he has made on the back veranda and is roasting the Christmas goose, though he is almost too drunk to crouch without toppling headlong into the flames. The only thing that seems to keep him a reasonable distance from the fire is his anxiety not to catch the end of his enormous, newspaper-rolled joint on fire. He rocks and swings and sings. Everyone within a thirty-mile radius of our farm is drunk.

Except our freshly arrived guests, hair uncomfortably pressed into place, polite in new Christmas dresses and ties, throat-clearing at the sitting room door.

Mum, mud-splattered and cheerfully sloshed, is determined to inject the Christmas cake with more brandy before its appearance after the goose.

Dad is in a worryingly deep alcoholic coma. His lipstick is smudged. His snores are throaty and deep and roll into the sitting room from the bedroom section.

It is long after noon when the goose is cooked, by which time our Christmas guests are drunk, too. One has fallen asleep on the pile of old flea-ridden carpets and sacks that make up the dogs’ bed.

We wear paper hats and share gin from another watermelon porcupine. We eat goose and lamb, potatoes, beans, and squash all rich with the taste of wood smoke. Adamson is asleep against a pillar on the back veranda; the rain blows in occasionally and licks him mildly wet. His soft, enormous lips are curled into a happy smile.

When the Christmas cake appears on the table, there is a moment of quiet expectation. It is the ultimate gesture of a proper English Christmas. Mum has made brandy butter to accompany the cake.

“I’ve soaked the cake in a little brandy, too,” says Mum, who is as saturated as the cake by now. She tips a few more glugs onto the cake, “just to be on the safe side,” and refills her own glass.

“Now we light it,” says Vanessa.

Mum struggles to light a match, so the guest from Zimbabwe offers his services. He stands up and strikes a match. We hold our breath. The cake, sagging a little from all the alcohol, is momentarily licked in a blue flame. A chorus of ahs goes up from the table. The flame, feeding on months of brandy, gathers strength. The cake explodes, splattering ceiling, floor, and walls. The guests clap and cheer. We rescue currants and raisins and seared cake flesh from the pyre and douse our scraps in brandy butter.

Zoron (a Muslim) raises his glass. “Not even in Oxford,” he pronounces in a thick Yugoslav drawl, “can they have such a proper,

pukka

Christmas, eh?”

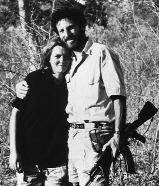

Bo and Charlie

CHARLIE

I’ve been overseas, in Canada and Scotland, at university. The more I am away from the farm in Mkushi, the more I long for it. I fly home from university at least once a year, and when I step off the plane in Lusaka and that sweet, raw-onion, wood-smoke, acrid smell of Africa rushes into my face I want to weep for joy.

The airport officials wave their guns at me, casually hostile, as we climb off the stale-breath, flooding-toilet-smelling plane into Africa’s hot embrace, and I grin happily. I want to kiss the gun-swinging officials. I want to open my arms into the sweet familiarity of home. The incongruous, lawless, joyful, violent, upside-down, illogical certainty of Africa comes at me like a rolling rainstorm, until I am drenched with relief.

These are the signs I know:

The hot, blond grass on the edge of the runway, where it is not uncommon to see the occasional scuttling duiker, or long-legged, stalking secretary birds raking the area for grasshoppers.

The hanging gray sky of wood smoke that hovers over the city; the sky is open and wide, great with sun and dust and smoke.

The undisciplined soldiers, slouching and slit-eyed and bribable.

The high-wheeling vultures and the ground-hopping pied crows, the stinging-dry song of grasshoppers.

The immigration officer picks his nose elaborately and then thumbs his way through my passport, leaving greasy prints on the pages. He leans back and talks at length to the woman behind him about the soccer game last night, seemingly oblivious to the growing line of exhausted disembarked passengers in front of him. When, at length, he returns his attention to me, he asks, “What is the purpose of your visit?”

“Pleasure,” I say.

“The nature of your pleasure?”

“Holiday.”

“With whom will you be staying?”

“My parents.”

“They are here?” He sounds surprised.

“Just outside.” I nod toward the great mouth of the airport, where there are signs warning tourists not to take photographs of official buildings—the airport, bridges, military roadblocks, army barracks, and government offices included. On pain of imprisonment or death (which amount to the same thing, most of the time, in Zambia).

The officer frowns at my passport. “But you are not Zambian?”

“No.”

“Your parents are Zambian?”

“They have a work permit.”

Mum and Van

“Ah. Let me see your return ticket. I see, I see.” He flips through my ticket, thumbs my inoculation “yellow book” (which I have signed myself—as Dr. Someone-or-Other—and stamped with a rubber stamp bought at an office supply store to certify that I am inoculated against cholera, yellow fever, hepatitis). He stamps my passport and hands my documents back to me. “You have three months,” he tells me.

“Zikomo,”

I say.

And his face breaks into a smile. “You speak ‘Nyanja.”

“Not really.”

“Yes, yes,” he insists, “of course, of course. You do. Welcome

back

to Zambia.”

“It’s good to be home.”

“You should marry a Zambian national; then you can stay here forever,” he tells me.

“I’ll try,” I say.

Vanessa gets married first, in London, to a Zimbabwean.

The little lump under the wedding dress, behind the bouquet of flowers, is my nephew.

Mum, very glamorous in red and black, sweeps through the wedding with a cigar in one hand and a bottle of champagne in the other. She looks ready to fight a bull. She takes a swig of champagne and it trickles down her chin. “God doesn’t mind,” she says. She takes a pull on her cigar; great clouds of smoke envelop her head and she emerges, coughing, after a few minutes to announce, “Jesus was a wine drinker himself.”

In the end, I don’t marry a Zambian.

I’ve been up in Lusaka, between semesters at university, riding Dad’s polo ponies, when I spot my future husband. I’ve just turned twenty-two.

I can’t see his face. He’s wearing a polo helmet with a face guard. He is crouched on the front of his saddle and is light in the saddle, easy with the horse, casual in pursuit of the ball.

“Who

is

that?”

An American, it turns out, running a safari company in Zambia, whitewater and canoe safaris on the Zambezi River.

I ask if he needs a cook for one of his camps.

He asks if I’ll come down to the bush with him on an exploratory safari.

Everyone warns him, “Her dad isn’t called Shotgun Tim for nothing.”

Dad is not going to have two daughters pregnant out of wedlock if he has anything to do with it. Dad has told me, “You’re not allowed within six feet of a man before the bishop has blessed the union.” He has set a watchman up outside the cottage in which I now sleep. The watchman has a panga and a plow-disk of fire with which to discourage visitors. Although any visitor would also have to brave the trip down to the farm on the ever-disintegrating roads. Anyway, since Vanessa left home and married, the torrent of men that used to gush to our door from all over the country has dwindled to a drought-stricken trickle.

Charlie tells his river manager to make up a romantic meal for the wonderful woman he is bringing to the bush with him. Rob knows me. He snorts, “That little sprog. She’s your idea of a beautiful woman?”

Rob knew me when I was tearing around the farm on a motorbike, worm-bellied and mud-splattered. He saw me the first time I got drunk and had to go behind the Gymkhana Club to throw up in the bougainvillea. He knew me before I was officially allowed to smoke. He used to look the other way while I sneaked cigarettes from his pack on top of the bar.

Charlie and I leave the gorge under hot sun and float in canoes into the open area of the lower Zambezi. At lunch we are charged by an elephant. I run up an anthill. Charlie stands his ground. When we resume the float, several crocodiles fling themselves with unsettling speed and agility into the water, where I imagine them surging under our crafts. We disturb land-grazing hippos, who crash back onto the river, sending violent waves toward us. When we get to the island on which Rob (coming down earlier by speedboat) has left tents and a cold box, Charlie disturbs a snake, which comes chasing out of long grass at me.

We set up the tent, make a fire, and then open the cold box to reveal Rob’s idea of a romantic meal for a beautiful woman: one beer and a pork chop on top of a lump of swimming ice.

That night there are lion in camp. They are so close we can smell them, their raw-breath and hot-cat-urine scent. A leopard coughs, a single rasping cough, and then is silent. A leopard on the hunt is silent. Hyenas laugh and

woo-ooop!

They are following the lion pride, waiting for a kill, restless and hungry and running. Neither of us sleeps that night. We lie awake listening to the predators, to each other breathing.

The next weekend I take Charlie back to Mkushi with me to introduce him to Mum and Dad.

Dad is standing in front of the fireplace when we arrive. It’s a cool winter day and now the fire is lit at teatime. Mum is all smiles, great overcompensating smiles to make up for the scowls coming from Dad.

She says, “Tea?”

We drink tea. The dogs leap up and curl on any available lap. The dog on Charlie’s lap begins to scratch, spraying fleas. Then it licks, legs flopped open. Charlie pushes the dog to the floor, where it lands with astonishment and glares at him.

Dad and Bo

Dad says, “I understand you took Bobo camping.”

“That’s right,” says Charlie pleasantly. He is tall and lean, with a thick beard and tousled, dark hair. He is too tall to see into the mirror in African bathrooms, he told me. So he has no idea how his hair looks. It looks like the hair of a passionate man. A man of lust.

Dad puts down his teacup and lights a cigarette, eyeing Charlie through the smoke. He says, “And how many tents, exactly, were there?”

“One,” says Charlie, blindsided by the question.

Dad clears his throat, inhales a deep breath of smoke. “One tent,” he says.

“That’s right.”

“I see.”

There is a pause, during which the dogs get into a scrap over a saucer of milk and the malonda comes noisily around the back of the house to stoke the Rhodesian boiler with wood, so that there will be hot water for the baths tonight.

“There’s a very good bishop,” Dad says suddenly, “up in the Copperbelt. The Right Reverend Clement H. Shaba. Anglican chap.”

It takes Charlie a moment or two for the implications of this statement to sink in. He says, “Huh.”

“My God, Dad!”

“One tent,” says Dad and puts down his teacup with crashing finality.

Mum says, “I think we’d all better have a drink, don’t you?”

“Dad!”

“End of story,” says Dad. “One tent. Hm?”

We are married in the horses’ paddock eleven months after we first meet. Bishop the Right Reverend Clement H. Shaba presiding. Mum is wearing a vibrant skirt suit of tiny flowers on a black background, with hat to match. Vanessa is billowing and mauve, pregnant with her second son. Trevor, her first son, is in a sailor suit. Dad is dignified in a navy blue suit, beautifully cut. He could be anywhere. He comes to fetch me in a Mercedes-Benz borrowed from the neighbors, where I have spent the night before the wedding. He says, “All right, Chooks?”

I’ve had a dose of hard-to-shake-off malaria for the last two weeks. “A bit queasy,” I tell him.

It’s ten-thirty in the morning. Dad says, “A gin and tonic might buck you up.” He has brought a gin and tonic on ice with a slice of lemon in a thick glass tumbler from the farm. It’s in a cardboard box on the passenger side of the car.

“Cheers.” I drink.

“Cheers,” he says, and lights a cigarette, shaking a spare stick to the surface of the packet. “Want one?”

“I quit. Remember?”

“Oh, sorry.”

“ ‘S okay.”

We drive together in silence for a while. It’s June, midwinter: a cool, high, clear day.

“Pierre’s cattle are holding up nicely,” my father says.

“Nice and fat.”

“Wonder what he’s feeding?”

“Cottonseed cake, I bet.”

“Hm.”

We slow down to allow a man on a bike, carrying a woman and child over the handlebars, to wobble up and over the railway tracks.

“Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do . . .”

Dad looks at me and laughs. Now we’re close to the farm.

“Oh, God,” I say.

“What?”

“Nerves.”

“You’ll be all right,” says Dad.

“I know.”

“He’s a good one.”

“I know.”

I pull down the mirror on the passenger side and fiddle with the flower arrangement on my head. “I think this flowery thing looks silly, don’t you?”

“Nope.”

“You sure?”

“You’re not bad-looking once they scrape the mud off you and put you in a dress.”

I make a face at him.

“All right, Chooks.” He leans over and squeezes my hand. “Drink up, we’re almost there.”

I swallow the rest of my gin and tonic as we rock up the uneven driveway, and there is the sea of faces waiting for me. They turn to see Dad and me climb out of the car. There are farmers from the Burma Valley and Malawi, in too-short brown nylon suits. There are farmers’ wives in shoulder-biting sundresses, already pink-faced from drinking. Children are running in and out of the hay bales that have been set up for the congregation. Old friends from high school wave and laugh at me. Farm laborers stand; they are quiet and respectful.