Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (20 page)

Read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Nonfiction, #Biography, #History

I watch Mum carefully. She hardly bothers to blink. It’s as if she’s a fish in the dry season, in the dried-up bottom of a cracking riverbed, waiting for rain to come and bring her to life.

Vanessa says, “Leave her alone, she’s depressed.”

Vanessa seems a bit depressed herself.

I say, “Anyone hungry?”

Mum pours herself another brandy.

“Aside from me?”

Since Thompson left, Judith/Loveness has been the only help in the house, but she can’t clean very well and she really can’t cook. I tell her to open a tin of baked beans and cook some bread on the wood fire to make toast for supper.

“With some boiled eggs,” I add.

When supper arrives I lay the table and shout, “Grub’s up!” but Mum doesn’t want to eat, and Vanessa pushes a few beans around on her plate before going back to her room. I am left to eat toast, an entire tin of baked beans, and three boiled eggs on my own.

Mum goes into the bathroom, where she wallows around in a humid steam for some time before emerging stupefied and reeling, wrapped in a towel. I have been entertaining myself, feeding the dogs the leftover supper one baked bean at a time.

Mum stands in front of the window in the living room, without music, swaying to nothing. I put the supper dishes on the floor for the dogs to lick and fish the Roger Whittaker record out of the Chopin sleeve. It seems better if Mum is swaying to music, even if the music is Roger Whittaker, than if she is swaying into the deep, animal-scampering, cricket-calling, moth-bashing silence.

“Ahm gonna leave ole London town, Ahm gonna leave ole London town. . . .”

I stand in front of her, in an effort to distract her. Her eyes slide glassily past me.

“Mum!”

She says in a low whisper, “You know they tried to kill Oscar.”

I say, “I know. You told me already.”

Mum looks over her shoulder and leans forward, almost overbalancing. “They think I’m unstable.”

“Do they?”

Mum smiles, but it isn’t an alive, happy smile, it’s a slipping and damp thing she’s doing with her lips which looks as much as if she’s lost control of her mouth as anything else. “They think I’m crazy.”

“Really?”

“But I’m not, I’m not at all.”

“No.”

“It was a

warning.

”

“What was a

warning

?”

“First Thompson, then Oscar, then Burma Boy . . .”

“But Burma Boy got horse sickness and tetanus. The managers had nothing to do with that.”

Mum’s eyes quiver. Her towel is slipping. “I’m next, you know.”

“For what?”

“But it doesn’t scare me.”

“No.”

The towel falls off completely. I retrieve it, and Mum clutches it over her breasts. “I know what they’re up to.”

“Oh, good.”

“No, it’s not good.”

“No.”

“A leopard a week. I see them. They think I’m crazy, but I see them. It’s illegal, you know.”

“I know.”

“Leopard are Royal Game. You have to have a permit.”

“I know.”

“They could go to jail.”

“I know.”

Vanessa comes out of her room; she turns off the record player and takes Mum by the elbow. “Why don’t you go to bed, Mum? I’ll bring you some hot milk.”

“Yuck.”

“Cold milk.”

“Yuck.”

“How about some tea?”

Mum allows herself to be led to the bedroom. Vanessa dresses her and puts her into bed. “Stay there, okay, Mum?” As she leaves the room she hisses at me, “Don’t let Mum get out of bed.”

“Right.” I sit on the edge of the bed, pinning down the bedclothes, and watch Mum, who is staring at the ceiling. “They invited me to a party,” she says in a dreamy voice.

“Who?”

“The managers. They had houseguests from town.”

“When?”

“You were away at school.”

“Was it fun?”

“They tried to poison me.”

“Oh.”

“Then when I was in the bathroom trying to throw up the poison, one of their guests tried to . . . to assault me.”

Mum suddenly sits up and I am scared of her, the way I would be scared of a ghost. I draw back, suppressing an urge to run away. She is behaving supernaturally. She is pale and drawn and there is sweat on her forehead and a thin mustache of sweat clings to her top lip. Her eyes are shining like marbles, cold and hard and glittering. She says, “You watch out for yourself.”

“I will.”

Vanessa comes in with the tea. “Go and bath, Bobo.” I flee, relieved.

Afterward Vanessa comes into my room and says, “You mustn’t pay too much attention to Mum. She’s just having a nervous breakdown.”

I have an arrow, confiscated from a poacher, hanging on my otherwise bare walls.

Vanessa frowns at it. “It’s about time you had some pictures in your room.”

“Why?”

“You’ll get morbid, looking at that thing all the time.”

“I like it.”

“

Ja,

but it’s not normal.”

“Nothing’s normal anymore, hey. Everything’s wrong.”

“It’ll be okay.”

“Why are the managers trying to kill Mum?”

“No, they aren’t.”

“That’s what she told me.”

“They aren’t, okay?”

“They tried to kill Oscar.”

“Maybe that was the Africans.”

“And they beat up Thompson.”

“That

was

the Africans.”

“Mum said they tried to poison her.”

“Ignore her. I told you already, she’s just having a nervous breakdown.”

“Then why are there so many bad-luck things at once?”

“Bad-luck things happen. That’s just the way it is. They happen all the time. It doesn’t mean anything, Bobo. It doesn’t mean that the bad-luck things have anything to do with each other. If you start thinking that bad luck comes all together on purpose or that it has to do with the managers or with you or with anything else, you’ll go bonkers.”

“Mum’s already bonkers.”

“Which is why she thinks all the bad-luck things are to do with the managers.”

I wipe my nose on my arm.

“You’ve really got to stop doing that,” says Vanessa.

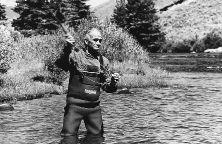

Dad comes back from fishing. He has had one bite in three days, and has caught nothing.

“We’ll move to a place where we can catch a fish just by yawning in the right direction,” he tells us.

I look at Mum and wonder how we’re ever going to move her anywhere.

“What do you think, Tub?”

Mum gives Dad her glazed smile and says, “Sounds fine.” Her voice is blurred.

“Mum hates fishing,” I point out.

“Yeah,” says Mum, laughing in a wobbly unhappy way, “I hate fishing.”

“See?”

“Well, we can’t stay here,” says Dad.

“Come back for my body in the dry season,” says Mum.

“What?”

“Nothing.”

I say to Dad, “I don’t think Mum’s well enough to go anywhere.”

“The change’ll do her good. She’ll be fine once we’re in a new place.”

“How do you know?”

“Because we’ve done it before. It’s no good wallowing around in the same place too long. Too much . . . too many . . . It makes you morbid.”

“Vanessa says I’m morbid.”

“See?”

I stroke the dogs with my foot. “What about Oscar and Shea? And the cats?”

“We’ll bring everyone with us.”

“And the horses?”

“We’ll see.”

Dad

MOVING ON

Mum is living with the ghosts of her dead children. She begins to look ghostly herself. She is moving slowly, grief so heavy around her that it settles, like smoke, into her hair and clothes and stings her eyes. Her green eyes go so pale they look yellow. The color of a lioness’s eyes through grass in the dry season.

Her sentences and thoughts are interrupted by the cries of her dead babies.

Only Olivia has had a proper funeral. Richard and Adrian are in unmarked graves. They float and hover, un-pressed-down. For them, there is no weight of dignity such as is afforded the dead by a proper funeral. There is no dampness of tears on earth, shed during the ceremony of grieving. There is no myth of closure.

All people know that in one way or the other the dead must be laid to rest properly: burnt, scattered, prayed over, laid out, sung upon. Earth must be thrown upon the coffins of the dead by the living hands of those who knew or loved them. Or ashes of the dead must be scattered into the wind.

“We have offended against thy holy laws, / we have left undone those things which we ought to have done, / and we have done those things which we ought not to have done; / And there is no health in us.”

It doesn’t take an African to tell you that to leave a child in an unmarked grave is asking for trouble. The child will come back to haunt you and wrap itself around you until your own breathing stops under the damp weight of its tiny, ghostly persistence.

Mum’s world becomes increasingly the world she sees in the reflection of the window at night when the lights are humming, high and low in tune to the throb of the generator, and Roger Whittaker is playing on the record player. Mum’s towel slips lower over her full-of-milk breasts. I hear her crying in the bathroom when she’s squeezing them empty. Milk for no one, down the plug. Her towel hangs open at her bottom, where her thighs are blood-smeared from the tail end of childbirth. She seems to be grieving for the loss of this new baby in every way a body can grieve; with her mind (which is unhinged) and her body (which is alarming and leaking).

While Mum sways damply in the insect, hot-singing night, crooning with Roger, “Ahm gonna leave ole London town,” Dad sits in the corner, under the lightbulb, ducking the moths and rose beetles that come in search of the light. He reads to himself, eyebrows raised in distant absorption, and smokes quietly. He is stretching a brandy and Coke into the night, sipping at it as if it were a delicate treat, although it has long since gone warm and flat. The dogs lie flattened on the concrete floor, their ears pressed to their heads, eyebrows anxiously raised.

That night I go into Vanessa’s room after the generator has been switched off.

“Van.”

“Ja?”

“Are you awake?”

She doesn’t answer.

“What do you think?”

She still doesn’t answer.

“Why won’t you talk to me?”

“You’re asking stupid questions.”

I grope my way to the end of her bed and lower myself next to the rising, bony hump of her feet.

“What do you think about Mum?”

“What about Mum?”

“Well . . .”

Silence.

“Don’t you think?”

Vanessa sighs and turns over. She’s fourteen now. I can feel the suddenly heavier, womanly shift of her. The bed sags under her newfound weight. She smells different, too—not dusty and metallic and sharp like puppy pee, but soft and secret and of tea and her new deodorant which comes in a white bottle with a blue label and which I covet. It’s called Shield. She says, “If Mum and Dad catch you out of bed you’ll be in the

dwang

.”

“They won’t catch me.”

Vanessa knows I’m right. She says, “I’m trying to sleep. You’re bugging me.”

Suddenly, surprisingly, I’m crying; mewing my sadness. Vanessa sits up and puts her arms awkwardly over me. “It’s okay, hey.”

“What’s going on, man?”

Vanessa rocks me. “Shhhh.”

“Why is everyone so crazy?”

“It’s not everyone.”

“It feels like it.”

Vanessa says, “If you promise to go to sleep, I’ll make a plan, okay?”

I sniff and wipe my nose on the back of my arm.

“

Sis,

man. I’ve told you about that.”

“I don’t have any bog roll.”

“Well get some. Blow your nose. Then go to bed.”

The next morning when I wake up, later than usual, with the sun eight o’clock high and hot in the dust-flung pale sky, Vanessa is already dressed. She has been arranging for the family’s healing; she has collected our fishing rods and hats and has packed a cardboard box with reels, fishing line, boiled eggs, beer, brandy, a cheap bottle of red wine, a loaf of bread, biltong, thin-skinned and bitter wild bananas, oranges.

“I’ve made a plan to go to the dam,” she announces at breakfast. “Let’s go fishing for catfish.”

Dad looks up from his porridge, surprised.

“I really think we should go fishing.”

“Mum hates fishing,” I say. “She isn’t even up yet.” Mum is having tea in her room.

Vanessa glares at me and then stares at Dad intently. “We need to go for a picnic.”

Dad says, “I have work. . . .”

“And we’ll take our fishing rods so you don’t get bored.”

Dad looks as though he’s about to protest further. He opens his mouth to speak but Vanessa gets up, pushes her hair out of her eyes, and says, “I’ve packed the lunch. I’ll go and get Mum.” She cocks her head. “Why don’t we ask that visitor chappy to come along?”

There is a young law student from South Africa staying on the ranch. His grandfather had been one of the original homesteaders of Devuli Ranch. Vanessa and I have been watching him hungrily through the binoculars since he arrived a few days earlier. He has a mass, like a wig, of curly blond hair. He’s been staying with the ranch managers, with whom we have been unofficially at war since Mum’s nervous breakdown. Vanessa and I met the visitor (we had stalked him) at the workshop and I grilled him unabashedly—who was he, what was he doing here, how long was he staying—until Vanessa dragged me off by the wrist and hissed at me, “You’re so embarrassing.”

“Why?”

“Why?”

“What did I do now?”

“Oh, God. Where do I start?”

Our captured guest (whom I have gloated over victoriously since his arrest, which took place in the ranch manager’s compound: “Come fishing with us. Please,” and then, not wanting to scare him off with my eagerness, “If you’d like”) has the unsettling, potentially unhealing name of Richard. But he’s young and cheerful and appears innocent of our recent and past traumas and Mum has responded to him, to his freshness, with the first true, unwobbly smile since she came back empty-armed from the hospital.

Vanessa and I make room in the back of the Land Rover for Richard, who swings up onto the little metal bench over the wheel with long-legged ease. I stare at him intently and smile fiercely. Vanessa nudges me hard in the ribs. She is looking nonchalantly out of her side of the Land Rover, aloof, composed. She has stopped wearing her hair in braids. Now it falls across her face in a blond sheet, so that she has scraped it around the back of her neck and is holding it against the slap of wind. She closes her eyes and lifts her face to the sun. I resume my hopeful, maniacal grinning, fixed on Richard.

It’s pointless trying to start a conversation with our captive, although I am tempted to warn him (to be fair) that Mum is crazy. The Land Rover rocks and swings and plunges, its engine roaring with the effort of off-off road. We have long since left the rib-shattering relative speed of the main dirt road (where the short wheelbase smacks the corrugations in the road at just the right interval to wind us) and we are beyond the barely made tracks which are really nothing more than an indication—some telltale wear—that someone else has come this way in the past. (In the thin, brittle soil, barely held together by the soft, burnt-up weight of grass, tracks from a single vehicle, covering the ground a single time, can show for years.) Now we are plunging between buffalo thorn and skirting anthills and we, in the back, are forced to swing forward (our hands tucked under us to prevent them from being raked by thorns) and duck.

We pass, without comment or surprise, small, rain-ready herds of impala. The ewes are swollen with impending babies, but the babies will come only with the first rain. Dad stops to let a pair of warthog charge fatly in front of us, round-bottomed and heads held high. A kudu bull stares us down—the perfect white “V” on his nose a hunter’s target. He is sniffing the air and then, with a magnificent leap, his horns laid across his back like medieval weapons, he is gone, plunging grayly into the crosshatched bush.

It is late morning by the time we get to the dam, and the sun has settled into the shallow, blanched mid-sky. The dam is shrinking, muddy, warm; its waters have receded, leaving a damp swath of cracking mud and strong smells of frog sperm and rotting algae. Egrets are poking along the edge of the dam. They rise when the dogs come flopping toward them, and settle, just beyond reach. Busy weavers chatter and fly, darting back and forth from their watertight, snake-savvy nests with pieces of grass trailing from their mouths.

It is the wrong time of year to be here. The sun has scorched the shade off all the trees, whose limbs now stretch, thin and hungry, into the arid, smoky sky. The ground is glitteringly hot. Vanessa pulls out some cushions and a deck chair and sets the chair up for Mum under the lacy protection of a buffalo thorn. Mum pours herself some tea from the thermos and, with the remote distraction she has maintained since the baby died, begins to read.

She smiles at Richard—“This is nice, isn’t it?”—and I want to sing wildly and shout for joy because it is such a normal thing to say, even though it is a lie. I want everyone to notice what a normal thing to say this is. I want to ask Richard, “Don’t you think she sounds normal?”

Dad and I find logs near the edge of the dam and begin to fish for barbel, whiskered fish that bury themselves into the mud in the drought years and reemerge only after the first rains. They are like vampire fish, coming back to life with a creepy insistence, year after year—even after years that have left a trail of skeletons in their wake. These fish are very hard to kill. We bash them brutally, headfirst, on rocks; still they thrash and squeal. They don’t seem fragile or fishlike at all. Dad and I take turns to jump on them, but they slither out from underfoot. Then we wrestle them to the ground (they are black and muscular, and slip easily from our grip) and one of us holds them down while the other smashes rocks on their heads. We leave their battered bodies in a net, suspended in the water so that they won’t rot in the heat.

“We’ll take them home for the

muntus,

” says Dad.

“What do they taste of?”

“Mud. They taste like the smell of this,” says Dad, digging his toe into the visceral dirt.

“Yuck.”

“

Ja,

but a

muntu

will eat anything.”

Vanessa has walked to the other side of the dam, where she can see Mum and where she can be seen by Richard, who has stationed himself, precariously, on a log that overreaches into the dam. He is straddling the log, head bowed exposing white neck to hostile sun, and is threading a worm onto his hook. His back is to Dad and me; his neck is already turning stung pink. The dogs nose around, always keeping one anxious, faithful eye on Mum, who looks unmovable, unmoving, unreading. In spite of her stillness, she is the one who seems most restless; her energy is snaking out of her like heat waves, dancing across the water to us, hot and insistent. Or perhaps it is my anxious energy dancing toward Mum: I’m like one of the dogs, trying to read her mood, her happiness, her next move.

Suddenly, Mum gets out of her chair and walks across the damp patch of smelly sticky mud toward the water, kicking mud off her toes as she walks, girlish in the gesture. Vanessa lifts her head—as if sniffing the air—and puts down her fishing rod. She has been watching Mum out of the corner of her eye all this time, but now that Mum has moved, Vanessa is riveted with indecision. Dad and I have propped our rods against rocks and have been crouched, haunches hanging, waiting for another bite. Dad shifts when Mum gets up, almost rising himself. The dogs come bounding back from where they have been exploring, mixing and stirring at Mum’s feet, suddenly playful. Only Richard is unaware of the un-drama unfolding at the water’s edge.

Like a woman hoping to drown, Mum is walking into the dam, fully clothed. She walks softly, shimmering behind the veil of heat.

“What the hell’s she doing?” Dad gets to his feet.

“Mum!” Vanessa starts to run toward her.

Mum continues to wade. Her shirt has floated up and is spread out on top of the water, blue and dry, briefly, until the muddy weight of the dam sucks it down. Mum can swim—poorly—but we all know that she has the willpower, the leaden weight of heartsickness, not to swim if she chose to let the murky water swallow over her head.

Vanessa is lumping awkwardly, slow-motion-panic, through the mud. “Mum!” Her voice is made sluggish with the dense heat.