Dog Sense (43 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Moreover, since dogs can tell each other apart by smell, they can surely learn the characteristic odors of the humans they live with or meet on a regular basis. They can probably also tell a great deal about our moods from the way these odor cues vary. Dogs can be specially trained to alert epileptic or unstable diabetic owners when they are about to have a seizure or hypoglycemic attack. There is little doubt that they do this by reacting to changes in the owner's odor (although minute changes in “body-language,” undetectable to human observers, may also be part of the cue). Even ordinary pet dogs can be trained to serve this purpose; no special olfactory ability seems to be necessary.

13

The implication is that all dogs are at least potentially able to monitor our moods based on the ways our body odor changes. (Of course, they must simultaneously allow for, and possibly try to interpret, other causes of our changing odor, such as our state of health and the different foods that we have eaten.) If so, they are picking up, and presumably reacting to, a vast range of information about our lives that we ourselves are only dimly aware of.

Perhaps one reason we can be so oblivious to the importance our dogs place on smell is how little they seem to suffer as a result of our ignorance. However, just as their ears can be damaged by the high levels of ultrasound produced by the clanging of metal kennel gates and furniture, dogs' noses must surely be insulted by what must seem to them to be the overpowering odors of our detergents, fabric softeners, and “room fragrances.” Presumably they just get used to them, accepting them as an unavoidable downside of sharing a living space with the humans they are so closely bonded to. In the hygiene-conscious world we live in, many of us don't like to let dogs do what they must feel compelled to do when they first meet us, which is to sniff us. I always hold out my hand to any dog I'm introduced to (I make a loose fist first, just in case the dog has a habit of nipping fingers). If the dog wants to lick my hand as well as sniff it, then I let himâI can always wash my hand later if I want to. Not doing so would be as unsociable as hiding our face from someone we're being introduced to.

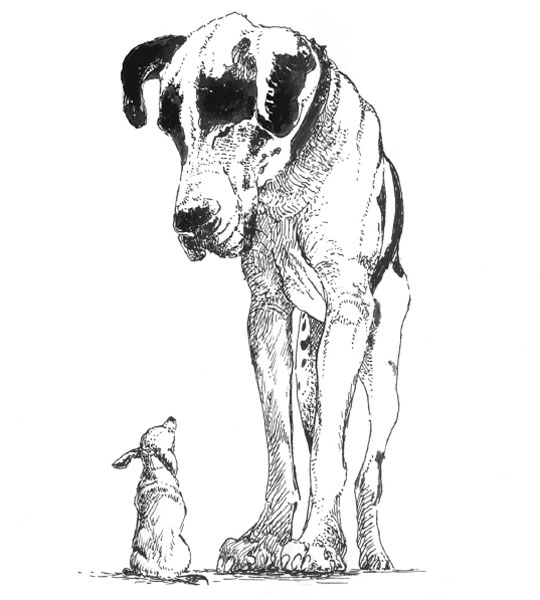

Perhaps it's just as well that we have only recently started to become aware of this “secret world” that dogs inhabit; otherwise, we might be tempted to interfere with it. We have certainly taken liberties with their visual communication, by breeding them into such diverse shapes and sizes. The potential for a Chihuahua and a Great Dane to misunderstand each other's visual signals seems almost unlimited, since they do not look like one another; nor, indeed, does either look much like a wolf. However, their scent glands, and the behavior that enables them to use these to communicate effectively, seem for all intents and purposes to be intact. It's quite possible that dogs' reliance on scent has been their salvation, enabling even breeds that look extraordinarily different from one another to go on conversing with one anotherâat some rather basic, smelly level.

Problems with Pedigrees

T

hroughout most of this book, I've discussed dogs as if they were all roughly equivalent. And for our purposes, this is very often true: Despite some inevitable variations between breeds, all dogs share an evolutionary past, an acute sense of smell, a capacity for forming strong bonds with people, and an ability to recognize one another as members of the same species and to interact with one another accordingly. However, dogs are self-evidently not all the same, and sometimes it's the differences between them that affect their well-being the most. The differences between dogs are primarily imposed by us, not by the dogs themselves. Where humankind doesn't interfere with breeding, dogs look pretty much the same; village dogs in Africa, for instance, are essentially indistinguishable. They evolve into a type that is adapted to the environment they find themselves in. When humans start to choose which dogs to breed from, however, they generate dogs who are, by definition, less well suited to that niche. Initially, this probably didn't matter at all. The capabilities that equip dogs to live on the street,

alongside

mankind, have gradually been replaced by those that allow dogs to live

with

man. These include not only changes that enable dogs to earn their living, such as helping with herding, hunting, and guarding (to name but three examples) but also those that enable dogs to be good companions.

However, as this process continued, there must have been many dogs whose well-being was compromised by humankind's attempts to produce more extreme forms. For example, the Romans bred their mastiffs

larger and larger, striving for fiercer and fiercer dogs. Some of these dogs must have been freaksâpuppies too large to pass through their mother's pelvis, or dogs whose skeletons were too heavy for their joints and thus in constant pain. In those rough-and-ready days, with precious little veterinary care, a crude kind of natural selection would have prevailed. Dogs who were not viable would have been stillborn or would not have lived long enough to breed, and dogs too infirm to perform their intended task would not have been selected for breeding.

Changes in rates of development have led to today's extremes of size and shape

Like all animals, dogs are capable of producing far more offspring than is necessary for the continuation of their species. Unless a population is growing rapidly, this inevitably means that many individuals die before reproducing. As a general rule, the ones who die first are those least well suited to their environment. Many will have suffered before they died.

This of course applies as much to village dogs as it does to dogs being bred by man for specific purposes. Nevertheless, the generation of new forms of dog inevitably left casualties in its wake.

Times have changed. In the West, we now believe in the right of each individual dog not to suffer. Puppies are no longer regarded as disposable items, to be drowned if unwanted. There is an outcry in the media whenever any cull of dogs is proposed, whether these be ferals, strays, or unwanted pets.

These are high standards indeed. We have taken upon ourselves the obligation to ensure that every puppy is wanted and will grow to be a healthy, happy dog. In many ways, we have succeeded in fulfilling these responsibilities. We have developed sufficient veterinary care to enable the majority of dogs to lead healthy lives. High-quality nutrition specifically designed for dogs is available in every supermarket, to the point that they have a healthier diet than some people do.

In other ways, however, we have failed our canine companions. In our seemingly insatiable quest for novelty, we have bred dogs who suffer from a vast range of avoidable ailments. And in our anthropomorphic need to see dogs as extensions of our own personalities, we have generated dogs that are unacceptably aggressive or have other temperamental defects. Their role as companionsâa role they must fill if they are to be assured of leading physically and psychologically healthy livesâseems rarely to be the first priority. Novice owners can be faced with choosing between pedigree puppies, primarily bred for appearance rather than temperament, and rescue dogs of uncertain parentage, many of whom will have been abandoned because they are the progeny of dogs bred for aggression.

Whereas dogs once made their own decisions about reproduction, nowadays in the West most matings are planned by humans. Over the past hundred years, specialists have increasingly come to control dog breeding. At present, most of our pet dogs either are pedigree dogs or can trace their ancestry just a few generations back to crosses between pedigree animals. By comparison with the whole history of the domestic dog, this is a very recent phenomenon, and one that is geographically and culturally confined: Genuinely ancient types of dog persist in many

parts of the world. Nevertheless, most of the dogs available as pets to Westerners have pedigree ancestors.

The current rules for breeding pedigree dogs are causing profound and accelerating harm to their genetic viability. The registration systems for pedigree dogs in the United Kingdom, the United States, and many other parts of the world confine each breed to mate only with other members of the same breed. If this system were to be imposed totally, each breed would become completely genetically isolated from all other dogs. (In actuality, owing to unplanned matings and occasional deliberate crossbreedings, only the pedigree breeds themselves have been sequestered in this way.)

Although most of these breeding regulations are very newâaffecting only the most recent one percent of the whole evolutionary history of the dogâthey are already having profound effects on the dogs we see today. The genetic isolation of each breed has brought about a dramatic change in the dog's gene pool, massively reducing the amount of variation in each breed. The less the variation, the more likely it is that damaging mutations will affect the welfare of individual dogs: In order for a potentially detrimental mutation to actually cause harm, it generally has to have been present in

both

parentsâand this is likely to occur only if the parents themselves are closely related. In some dog breeds today it is difficult to find two parents who are

not

closely related.

Until very recently, the amount of variation in the domestic dog was sufficient to maintain genetic health. Multiple domestications and back-crossings with wolves have meant that dogs worldwide still have an estimated 95 percent of the variation that was present in the wolves during the time of domestication. Most of this variation lives on today in street dogs and mongrels, but pedigree dogs have lost a further 35 percent. That may not seem like much, but let's imagine the scenario in human terms. Mongrels maintain levels of variability that are similar to those found globally in our own species. In many individual breeds, however, the amount of variation within

the whole breed

amounts to little more than is typical of first cousins in our own species. And we humans know that repeated marriages between cousins eventually lead to the emergence of a wide range of genetic abnormalitiesâwhich is why

marriages between close relatives are taboo in most societies. It is astonishing that the same consideration has not been given to dogs.

Just a handful of prize-winning popular sires are used to father the majority of puppies. This has tremendously restricted the gene pool. For example, about eight thousand new golden retrievers are registered in the UK each year, with a total population of perhaps a hundred thousand. Over just the last six generations, inbreeding has removed more than 90 percent of the variation that once characterized the breed.

1

In a recent sampling of the Y (male) chromosomes of dogs in California, no variation

at all

was found in fifteen out of fifty breeds, indicating that most of the male ancestors of each and every dog in those breeds had been close relatives of each other.

2

Some of the other breeds surveyed had only a very little variation. In the context of the imported breeds in the studyâsuch as the Rhodesian ridgeback, the boxer, the golden retriever, the Yorkshire terrier, the chow chow, the borzoi, and the English springer spaniel, this is not surprising. Assuming that all Californian examples are likely descended from a small founder population, limited gene pools are to be expected; much more variability might have been apparent if the samples had been taken in other countries. Of more concern was the lack of variation in the three American breeds being studied, since these are more likely to be representative of those breeds worldwide. There was no variability

at all

in the fifteen Boston terriers tested, and only a small amount in the twenty-six American cocker spaniels and ten Newfoundlands. Conversely, a couple of breeds recently derived from street dogs, the Africanis (or Bantu dog) and the Canaan dog, showed levels of variation similar to those in mongrelsâbut this is the result of a deliberate policy among their breeders, who have seen the problems that popular sires have brought to other breeds of minority interest.

The inbreeding of dogsâthough utterly deleterious to themâis potentially a huge boon to mankind. The canine genome was chosen by geneticists as one of the first to be sequenced, precisely because the occurrence of so many inherited diseases in today's pedigree dogs provides scientists with abundant opportunities to study, and then devise cures for, their (much rarer) counterparts in humans. The gigantic, if unintended, global experiment that is modern pedigree dog breeding promises to bring cures for many of our own diseasesâand many years

sooner than if the research had had to be conducted in mice or other laboratory animals. This will undoubtedly benefit our own species, but what about the dogs? If they could grasp the implications of what we've done to them, what would our dogs have to say?