Dog Sense (12 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

The farm-foxes tell us that natural variation in tameness within a species can be sufficient, in at least one of the canids, to produce individuals that could be the ancestors of a domestic animal. This experiment thus provides us with a model for the initial separation between wild wolves and those that were naturally tame enough to live alongside people. The resources that the naturally tame wolves were able to obtain from humans must have been sufficient to allow them to adopt a new way of breeding. Instead of hiding them away in a den, the intrinsically “tame” mother wolves must somehow have allowed their cubs

access to humans, so that taming, and selection for tameness in subsequent generations, could proceed further. Underlying the onset of tameness are changes in the production of and reactivity to stress hormones, alterations that are evident from tame farm-fox and dog alike. However, the farm-foxes tell us nothing about the way that dogs gained the capacity to sustain social relationships simultaneously with their own species and with humans. Nor do they tell us anything about how dogs achieved their remarkable diversity of shapes and sizesâand yet this very diversity permits another, very different approach to understanding the subsequent phases in the domestication of the dog, once tameable wolves had begun their association with mankind.

Instead of comparing dogs with wolves, or trying to reconstruct the domestication process, we can find important information about how dogs came to be by examining the differences between breeds and types of modern dogs. The ways in which they differ from one another can provide clues as to how those changes in appearance might have come about. Since different-sized dogs appeared very early in the history of domestication, at least ten thousand years ago, it's possible that the processes that led to the diversification in body shape are the very same as those that permitted domestication to proceed beyond tameness. And since many of the differences between breeds and types of dogs are known to arise through alterations in the rates at which the body and behavior develop in early life (alterations that are reflected both in the outward appearance of the dog and in the way its behavior is organized), the emergence of these superficial differences is thus arguably the most important underlying process that has produced today's dogs.

Dogs come in so many shapes and sizes that they have long been a puzzle to zoologists, but in fact many of the changes can be accounted for by a common biological mechanism, the technical term for which is

neotenization

. Roughly speaking, this refers to the phenomenon whereby growth in some parts of the body stops while other parts continue to grow at the normal rate. If the whole skeleton stops growing earlier than usual but the internal organs continue to mature, then the result is a smaller-than-usual animal that is still capable of reproducing. Thus, for

example, the skeleton of an adult Lhasa apso is similar to that of a Great Dane puppy, but the Great Dane will continue to grow for many more months before it becomes sexually mature. If the growth of the skeleton is altered selectively, then the end result is a change in shape as well as a reduction in size. Thus the skull of an adult Pekinese has essentially the same proportions as that of a wolf fetus but its body is more dog-like. In “toy” dogs, the growth of the whole skeleton stops at what would be, for a wolf, a very early stage. In flat-faced dogs, the growth of parts of the skull is slowed to maintain the proportions of that of a fetal wolf.

We are now coming to understand even more about the physiology that underlies these differences in canid appearance. It turns out that the skull and skeleton of the wolf change shape dramatically between their genesis in the fetus and their final form in the adult, under the control of various hormones. Much of the size variation in today's dogs probably comes about through changes in the growth stages during which these hormones are produced, how much is produced, and how effective they are at doing their job. Thanks to all the work that is going on to unravel the canine genome, it should soon be possible to identify how these changes work.

The very same principle of selective arrested development that governs dogs' growth can be used to explain how domestication molded the dog's behavior. For example, dogs continue to play even when they are adults, unlike most animals. Because the behavior of juvenile wolves is more flexible than that of the adults, the dog has been likened to a wolf that has never grown up, except in the important sense that it becomes sexually mature and so can reproduce. Its behavioral development has, in a sense, been arrested. The farm-fox story sheds important light on this process by telling us that tameable wolves probably differed from untameable wolves in having a delayed period of social learning at the beginning of their lives, such that tolerance of human contact had time to develop. Dogs, for their part, are like tameable wolves in which development of behavior has been slowed down further still, to the point that it becomes arrested at the (wolf's) juvenile stage, where behavior is more flexible and can therefore be adapted much more easily to the requirements of humans. Some simple resetting of the dials that control

the development of brains and behavior can, in theory, account for much of the transition from wild wolf to tame, from tame to domestic, and then to the diversification of dogs into types of different sizes and shapes.

One further difference between dogs and wolves can be accounted for by a selective change in the development of the two animals: Dogs become sexually mature somewhat

earlier

than wolves do. Dogs are also fertile throughout the year, unlike wolves, which are sexually active only in the winter, leading up to the birth of the cubs in the spring. Both of these differences are likely to be consequences of the transition from the wild, with its seasonal but predictable food supply, to early human societies where food was more plentiful on average but also more unpredictable; proto-dogs that could breed any time after their first birthdays would have out-competed those that waited, as wolves do, until their second winter.

For the same reason that they need to be much more opportunistic in grasping opportunities for breeding, dogs are also much less choosy than wolves in their choice of sexual partners. This is evident from the Y-chromosome (paternal) DNA of today's dogs, which is much more diverse than their mitochondrial (maternal) DNA. Because wolves pair-bond, males and females are about equally likely to contribute to the DNA of the next generation. Given the promiscuous tendencies of male dogs, some males can potentially sire over a hundred litters in their lifetime, while many others leave no offspring at all. Bitches are constrained by the fact that they can produce only one litter per year. Moreover, the variability in male reproductive success appears to have been set up well before the creation of the modern breeds in the nineteenth century, suggesting that male promiscuity is an ancient, not a recent, trait of dogs.

The promiscuity of the male dog must have been one of the factors that helped man, first accidentally but then increasingly deliberately, to impose his own selection pressures on the species. Some of these choices might have been simply fanciful, such as a preference for a particular coat color or an especially “cute” faceâqualities of no particular consequence for the process of domestication. Other aspects of human behaviorâsuch as taking special care of the offspring of a bitch prized

for her trainability and loyaltyâmight have pushed the process of domestication along.

At the early stages of domestication, certainly up to the point that dogs became physically distinct from wolves, human intervention in breeding is unlikely to have been a conscious process and, indeed, may have been haphazard, as it remains to this day in village dogs. The archaeological record indicates that in some areas dogs may have disappeared entirely from some societies, only to be replaced hundreds of years later by immigrants from elsewhere. Other societies may have rejected dogs even when they were available: Although Japan was first colonized by mankind about eighteen thousand years ago, there is no record of dogs in the region until about ten thousand years agoâpresumably Japan's new inhabitants considered the dogs available in ancient China unsuitable, for some now impenetrable reason.

Despite the almost certain lack of early selective pressures from humans, over the course of several thousand years wolves must have made some kind of faltering progress toward becoming an animal that had many of the behavioral characteristics of today's dogs, even if it still looked much like a wolf. Certain physical changes, however, would likely have begun to occur during this time. Dependence on man for what was probably a rather erratic supply of food would have favored a reduction in body size. As dogs were transported into warmer climates, those with shorter, paler coats would have out-competed those with the wolf's long, darker fur, producing a conformation that survives in village dogs to this day.

Many of the other conformations that we see in today's dogs are also ancient. By ten thousand years ago, dog-keeping and therefore dogs themselves had spread throughout much of Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas; soon after this, and in many parts of the world, recognizably distinct types of dog appear. Over the next couple of thousand years, dogs diversified rapidly, so that by the time representational art became commonplace some five thousand years ago, there were already dogs for many purposes. Long-limbed, long-nosed sighthounds, superficially similar to the modern saluki or greyhound, were used for hunting.

9

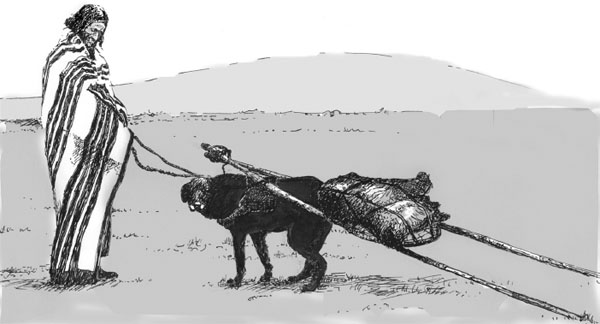

Heavy, large-headed mastiff types were used for guarding and general intimidation. Hounds were developed that hunted mainly by

scent, suited to finding and following large game in thick cover. Subsequently, larger dogs were found to be useful as pack animals, either carrying loads on their backs orâas widely practiced by some Native Americansâpulling a travois. Small terrier-like dogs were used for keeping rats and mice at bay and for hunting animals that go to ground, such as rabbits and badgers. Lap dogs, similar to today's Maltese dog, are first recorded from Rome more than two thousand years ago, but there were probably already lap dogs in China by this time, possibly the direct ancestors of today's Pekingese and pug. The arrival of lap dogs completed the process of generating the dog's remarkable variation in size; any that became smaller, or larger, would probably not have been biologically viable in the days before veterinary care. Lap dogs were also the first dogs bred solely for companionship, though for many centuries these through-and-through pets would have been rare compared to dogs kept for more utilitarian purposes.

Native American dog travois

We can be reasonably sure that there was a deliberate element in the breeding of all these dogs, over at least the last five thousand years, by the simple expedient of allowing bitches to mate only with chosen males of similar type. Some males were evidently favored over others: Molecular biologists have found much more variety in the mitochondrial

(maternal) DNA of dogs than in the Y-chromosome (paternal) DNA, indicating that during the entire history of the dog, far fewer males than females have left surviving offspring. Favored males must therefore have been prized and taken to mate with many bitches, much as happens today within pedigree breeds. The choice of male must sometimes have been based on body conformation (e.g., in dogs bred for food), but mainly it would have been based on whatever kind of behavior was desired in the puppies, whether suitability for herding, hunting ability, or guarding.

Dogs were almost certainly being bred deliberately as of five thousand years ago, and matings based on the dogs' own preferences would have kept the dog population diverse. Dog-keeping would have been much more chaotic than it is today, so many matings would also have been unplannedâand if the resulting offspring turned out to be useful, they would have been retained. Taboos against raising puppies that were not “purebred” would have been rare, unlike the situation today. Thus without any deliberate planning, a healthy level of genetic variation was maintained within types, as well as between. Transfer of dogs from one location to another by traders would have ensured that most local populations were not reproductively or genetically isolated from one another, maintaining diversity at the local as well as global levels. In the absence of veterinary knowledge, natural selection would have continued as a major force directing the development of dogs in general; the rates of both reproduction and mortality would have been much higher than they are today, at least in the West. Dogs who were prone to disease or infirmity, or carried other disadvantages, such as difficulty in whelping, would have left few offspring, and their lineages would eventually have died out.

As the modern world developed, so did the degree of deliberate breeding, for purposes that were increasingly diverse and narrow in definition. For example, further specialization within the existing range of sizes and shapes occurred in medieval Europe, where the importance of hunting to the new aristocracy led to the breeding of many specialist kinds of hound, each with its own local variationsâdeerhounds, wolf-hounds, boarhounds, foxhounds, otterhounds, bloodhounds, greyhounds,

and spaniels, to name but a few, although these are not necessarily the direct ancestors of the breeds that bear the same names today.