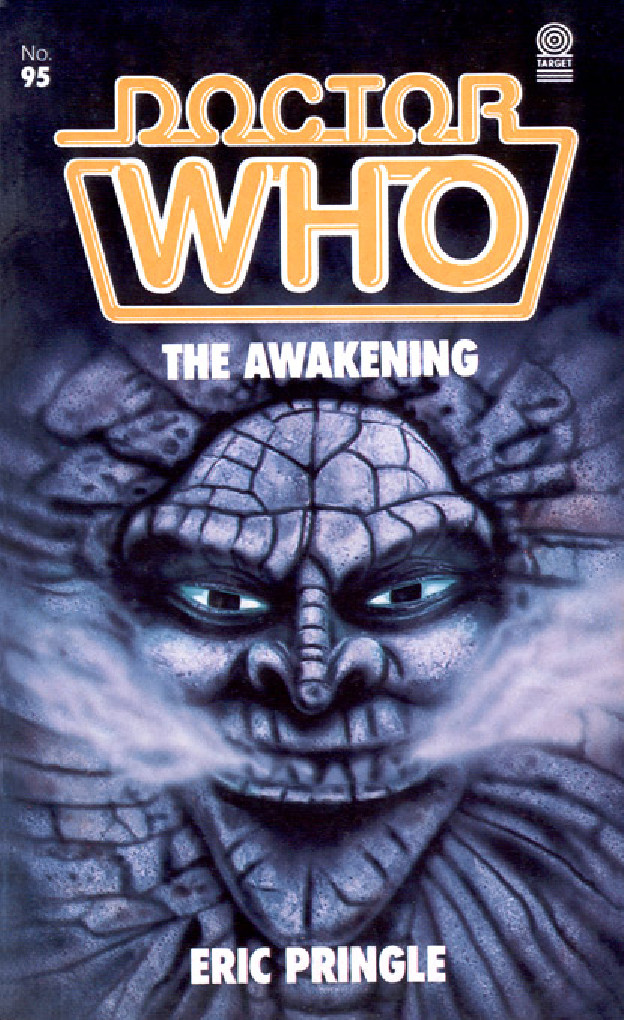

Doctor Who: The Awakening

The Doctor has promised Tegan that they will visit her grandfather in the English village of Little Hodcombe, in the year 1984, a precision of timing and location that the TARDIS has not always achieved . . .

When the Type-40 machine comes to a rest, the view on the scanner screen only serves to confirm Tegan’s rather low expecations of the TARDIS’s performance.

The most sensible course of action would be to leave immediately – but despite Turlough’s protests the Doctor rushes out to take on a seemingly hopeless rescue mission . . .

DISTRIBUTED BY:

USA: CANADA:

AUSTRALIA:

NEW

ZEALAND:

LYLE STUART INC.

CANCOAST

GORDON AND

GORDON AND

120 Enterprise Ave.

BOOKS LTD, c/o

GOTCH LTD

GOTCH (NZ) LTD

Secaucus,

Kentrade Products Ltd.

New Jersey 07094

132 Cartwright Ave,

Toronto,

Ontario

I S B N 0 - 4 2 6 - 2 0 1 5 8 - 2

UK: £1.50 USA: $2.95

*Australia: $4.50 NZ: $5.50

Canada: $3.95

,-7IA4C6-cabfii-

*Recommended Price

Science Fiction/TV tie-in

DOCTOR WHO

THE AWAKENING

Based on the BBC television serial by Eric Pringle by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation

ERIC PRINGLE

Number 95

in the

Doctor Who Library

A TARGET BOOK

published by

The Paperback Division of

W. H. Allen - LONDON

1985

A Target Book

Published in 1985

by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. PLC

44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB

Novelisation copyright © Eric Pringle 1985

Original script copyright © Eric Pringle 1984

‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1984, 1985

The BBC producer of

The Awakening

was John Nathan-Turner, the director was Michael Owen Morris Printed and bound in Great Britain by Anchor Brendon Ltd, Tiptree, Essex

ISBN 0 426 20158 2

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

1

Somewhere, horses’ hooves were drumming the ground.

The woman’s name was Jane Hampden, and that noise worried her. She was a schoolteacher, but just now her village school and its unwilling pupils were far from her thoughts: her mind raced with problems and uncertainties, making her head ache; she felt that if she did not share them with someone soon, she would go mad.

Jane was looking for farmer Ben Wolsey, but she could not find him anywhere. That was another problem, because time was short, and there were horses coming.

It was Jane’s belief that the village of Little Hodcombe was being torn apart. She felt instinctively that those horses had something to do with it, like the recent bursts of violence and the cries and shouts which so frequently disturbed the peaceful countryside. She was sure, too, that the mysterious disappearance of her old friend Andrew Verney was connected in some way.

And there was another thing which bothered her, which she found more difficult to put into words. In a quiet, remote place like Little Hodcombe, tucked away as it was deep in the lush Dorset hinterland, far away from cities or politics or any sort of world-shattering event, it was as normal as daylight that everybody should know pretty well everything about everybody else: you didn’t mind your own business here so much as you minded other people’s.

Jane was no different from the rest in this respect, and yet suddenly she felt that she didn’t know anything any more.

All at once, the place and its people seemed somehow strange, as if that normal, everyday life of thatched houses and quiet corners and fields and streams which composed Little Hodcombe was slipping away and being replaced by a new, nameless void, which contained only premonitions, and fears, and noises like this distant jingle of harness and the beating of those hooves on the baked earth.

Jane hurried through Ben Wolsey’s farmyard, searching for him and pondering on these things. She knew it must be nonsense – that perhaps she really was going mad - yet it seemed to her that the simple rules which governed daily living, basic things like the fact that today is reliably today and not tomorrow or yesterday, and that what is past and dead and gone really is so, no longer applied so firmly as they used to do. The behaviour of ordinary people was becoming extraordinary, and unpredictable, and strange.

Nobody believed her when she told them her fears.

They thought she was just being silly; that she was a nuisance and a killjoy. And it was equally useless for Jane to tell herself that she was deluded, and that these were fantasies quite unfit for a forward-looking young schoolteacher in 1984. She pretended twenty times a day that everything was as it should be. She looked out at Little Hodcombe and it was manifestly the same as it had always been. it smelt the same as it always had, and when she touched its buildings for reassurance they felt as they must have felt for centuries.

And yet she

knew

that it wasn’t the same How, though, could she possibly make anyone believe her when she was uncertain what had happened and couldn’t find the words to describe how she felt? But she was determined to make this one last attempt. She would get Ben Wolsey, who had always been a staunch friend, on to her side – surely Ben, the burly down-to-earth farmer that he was, would listen to her, and try to understand.

Unless, of course, the sickness had got to him too. He was not to be found, and those horses were coming closer by the second. Jane felt the vibrations of their hooves under her feet, trembling through the clay of the farmyard which had dried hard as brown concrete over weeks of unusually but sun and cloudless blue skies. This constant sunlight was abnormal in England. It made her dizzy. It dazzled her now with its harsh bright glare on the weathered red brick and blue paint-work of the farm buildings which enclosed the yard. It warmed her head as she hurried from one building to another, calling for the absent farmer, moving from barn to byre to implement shed, looking into doorways where the glare ended in a sharp black line of shadow.

‘Ben?’ she shouted.

She stood on tiptoe and looked over a stable door into the inky blackness of a shed, but the darkness was like a wall and she could see nothing. There was no reply.

Listening for sounds of movement, she heard insects murmuring in the heat, vibrating the air. And nothing else.

Jane brought her head back out into the sunlight. The air out here was vibrating too, with the chatter of unseen birds. Suddenly she felt uneasy. She hummed quietly to cheer herself up and hurried on to the next building.

She was a small, attractive woman, neat in white shirt and grey waistcoat, green corduroy jeans and boots. She wore her hair tied up in a bun, to make her look taller than she really was; wisps of it hung loosely about her forehead.

She carried a green knitted jacket slung casually over her shoulder in case the breeze which now and then fanned the farmyard should grow into something stronger: with the English climate, even in the middle of a drought you could never be sure.

She was no longer sure of anything.

Again Jane stood on tiptoe to peer over another stable door into another black hole. ‘Ben!’ she asked of the murky interior. Again it swallowed up her voice, and returned nothing except the whine and whirr of swarming flies.

But the horses were coming. In the yard the noise of their hooves was stronger and the vibrations were more distinct. Jane was sure she could hear harness jingling; the breeze which flipped the loose strands of hair on her forehead brought rhythmic clashing sounds to her ears.

Worried, she pushed her hair back into place, thrust her hands into her pockets and ran to another doorway.

‘Are you there, Ben?’ she demanded. There was no response here either; she was alone with the disembodied sounds of unseen insects, birds and horses. It was uncanny.

And then, suddenly it was more than sounds. They were corning very fast – big heavy horses making the earth throb with the hammer blows of their feet, and they seemed to take over the world. Jane could no longer hear insects or birds, she was aware only of this one stream of noise bearing down on her.

And now there were voices too, rising above the hooves, men’s shouts encouraging the horses and spurring them to even greater speed. Startled, Jane moved across the farmyard to look out between the buildings at the surrounding countryside.

Like everything else, it seemed that the usually placid green landscape of fields and trees and hedgerows had altered its character. Instead of a gently pastoral scene it had become a page from her school history hooks: the seventeenth century was moving towards her across a field, thundering out of the misty past in the shape of three horses – two chestnuts flanking a grey – and riders flushed with the excitement and danger of the English Civil War.

They came abreast of one another. The horseman on the left had the broad, plumed hat and extravagantly embroidered clothing of a Cavalier of King Charles the First; the other two wore battledress – the steel breastplates and helmets of mounted troopers. The middle rider, on the big grey horse, carried a brightly coloured banner.

They were an awe-inspiring sight. With her hands on her hips and her mouth open in amazement, .Jane watched them approach the farm. When they neared the buildings the rider on the left spurred his horse and galloped ahead of the others. He came through the gap between the farm buildings; as he entered the farmyard and approached Jane he slowed to a canter. She had a clear view of a sharp-featured face, with waxed moustache, pointed heard and shoulder-length wig under the great nodding peacock feather which adorned his hat. He was the perfect image of a seventeenth-century Cavalier.

Jane was speechless. The Cavaller cantered past her with a supercilious stare. Now the troopers were in the farmyard too; their horses’ hooves clattered on the baked clay earth. They also passed by, paying her no heed at all.

Then something odd happened, as frightening as it was unexpected. The troopers wheeled their horses around to face Jane. The rider on the grey horse lowered his banner and pointed it straight at her, like a lance. And suddenly without warning he shouted and urged his horse into action. The point of the banner swept forward. They gathered speed, looming at Jane out of the shimmering heat of the enclosed farmyard.

Jane felt her stomach muscles contract with fear. Her open-mouthed wonder turned to disbelief at the sight of the lunging horse and its rider thundering towards her. All her senses concentrated on the banner; her whole attention narrowed to that single point of steel which held firm and steady, and pointed at her body like a skewer.

This can’t be happening, she thought, it’s impossible.