Digestive Wellness: Strengthen the Immune System and Prevent Disease Through Healthy Digestion, Fourth Edition (36 page)

Authors: Elizabeth Lipski

Rye

Rye

Soybeans

Soybeans

Sugar maple

Sugar maple

Wheat

Wheat

Yogurt

Yogurt

Many people experience gas and bloating when they start taking prebiotics, but these symptoms usually dissipate after a week or so; if they do occur, you can either continue your current dosage or lower the dosage and then increase it gradually. Human studies of prebiotic use show the greatest growth of helpful bacteria in the people who need it most, with benefits most evident at doses up to 10 grams daily. After you stop taking prebiotics, your internal bacteria will return to previous levels in about two to three weeks.

7

The GI Microbiome: Dysbiosis, a Good Neighborhood Gone Bad

Dysbiosis is not so much about the microbe as it is about the effect of that bacteria, yeast, or parasite on a susceptible person. It’s about the relationship between the microbe and the host. Dysbiosis can occur in the digestive system as well as on your skin, vagina, lungs, nose, sinuses, ears, nails, or eyes. Typically dysbiosis doesn’t appear as a classic type of infection. These imbalances generally simmer along. After all, if the microbes were too virulent, you’d die. It’s in their best interests to learn to coexist with you and not make you too uncomfortable so that you also just learn to live with it! Dysbiosis may express itself as irritable bowel syndrome in one person, migraines in another, eczema, psoriasis, autoimmune illness, depression, and other illnesses.

The term

dysbiosis

was coined by Dr. Eli Metchnikoff early in the 20th century. It comes from

dys-

, which means “not,” and

symbiosis

, which means “living together in mutual harmony.” Dr. Metchnikoff was the first scientist to discover the useful properties of probiotics. He won the Nobel Prize in 1908 for his work on lactobacilli and their role in immunity and was a colleague of Louis Pasteur, succeeding him as the director of the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Dr. Metchnikoff found that the bacteria in yogurt prevented and reversed bacterial infection. His research proved that lactobacilli could displace many disease-producing organisms and reduce the toxins they generated. He believed these endotoxins (toxins produced from substances inside the body) shortened life span. He advocated use of lactobacillus in the 1940s for ptomaine poisoning, a widely used

therapy in Europe. He was also the first to note that these benefits were greatest in babies and in the eldery.

In more recent decades, Metchnikoff’s work has taken a backseat to modern therapies, such as antibiotics and immunization programs, which scientists hoped would conquer infectious diseases. Microbes are extremely adaptable. In our efforts to eradicate them we have pushed them to evolve. Long before chemists created antibiotics, yeasts, fungi, and rival bacteria were producing antibiotics to ward each other off and establish neighborhoods. They became adept at evading each other’s strategies and adapting for survival. Because people have used antibiotics indiscriminately in humans and animals, the bacteria have had a chance to learn from it, undergoing rapid mutations. They talk to each other and borrow plasmids, which are incorporated into their genetic structure. As they shuffle their components, learning new evolutionary dance steps, superstrains of bacteria have been created that no longer respond to any antibiotic treatment. For instance, our immune systems normally detect bacteria by information coded on the cell walls. Now, in response to antibiotics, some bacteria have survived by removing their cell walls, so they’re able to enter the bloodstream and tissues unopposed, causing damage in organs and tissues. Given people’s rapid movement between countries, these new microbes have spread quickly throughout the world, increasing the risk of even more mutation and enhancement of the microbial defense system.

Dysbiosis weakens our ability to protect ourselves from disease-causing microbes, which are generally composed of low-virulence organisms. Unlike salmonella, which causes immediate food-poisoning reactions, low-virulence microbes are insidious. They cause chronic problems that go undiagnosed in the great majority of cases. If left unrecognized and untreated, they become deep-seated and may cause chronic health problems, including joint pain, diarrhea, chronic fatigue syndrome, or colon disease.

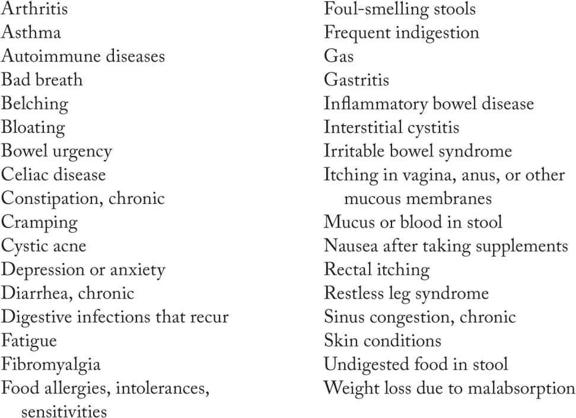

Because most doctors in our culture do not yet recognize dysbiosis, often people do not get well. Published research has listed dysbiosis as the cause of arthritis, diarrhea, autoimmune illness, B

12

deficiency, chronic fatigue syndrome, cystic acne, cystitis, the early stages of colon and breast cancer, eczema, fibromyalgia, food allergy or sensitivity, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, psoriasis, restless leg syndrome, and steatorrhea. These problems were previously unrecognized as being microbial in origin. Common dysbiotic bacteria are aeromonas, citrobacter, helicobacter, klebsiella, salmonella, shigella, Staphylococcus aureus, vibrio, and yersinia. Helicobacter, for example, is commonly found in people with ulcers. Citrobacter is implicated in diarrheal diseases. A common dysbiosis culprit, the candida fungus causes a wide variety of symptoms that range from gas and bloating to depression, mood swings, and premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

The lines between these types of dysbiosis often blur, and people often have more than one of these patterns.

Insufficiency dysbiosis:

Insufficiency dysbiosis:

This is when you don’t have enough “good” probiotic in your digestive system. This is common in people who took antibiotics as young children and in people who are currently taking or have taken many antibiotics. Low-fiber diets are another cause. Insufficiency dysbiosis is often seen in people with irritable bowel syndrome and food sensitivities and is often coupled with putrefaction dysbiosis. To restore balance, eat probiotic- and prebiotic-rich food and/or take supplemental probiotics, and eat 25 to 40 grams of fiber each day.

Putrefaction dysbiosis:

Putrefaction dysbiosis:

This occurs when you don’t have enough digestive enzymes, hydrochloric acid, and probiotic bacteria to enable you to fully digest your proteins. High-fat, high-animal-protein, low-fiber diets predispose people to putrefaction due to an increase of bacteroides bacteria, a decrease in beneficial bifidobacteria, and an increase in bile production. Bacteroides cause vitamin B

12

deficiency by uncoupling the B

12

from the intrinsic factor necessary for its

use. Research has implicated putrefaction dysbiosis with hormone-related cancers such as breast, prostate, and colon cancer. Bacterial enzymes change bile acids into 33 substances formed in the colon that are tumor promoters. Bacterial enzymes, such as betaglucuronidase, re-create estrogens that were already broken down and put into the colon for excretion. These estrogens are reabsorbed into the bloodstream, increasing estrogen levels. Putrefaction dysbiosis can be corrected by eating more high-fiber foods, fruits, vegetables, and grains, and fewer meats and fats.