Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) (975 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) Online

Authors: George Eliot

If too severe in some directions, this criticism is substantially sound. It does not matter what theory of personality we adopt, in a philosophical sense, if that theory upholds personal confidence and force of will. If it does not do this, the whole result is evil. This lack of faith in personality saddened all the work done by George Eliot. In theory a believer in an ever-brightening future, and no pessimist, yet the outcome of her work is dark with despondency and grief.

Life is sad, hard and ascetic in her treatment of it. An ascetic tone runs through all her work, the result of her theories of renunciation. The same sternness and cheerlessness is to be seen in the poetry and painting of the pre-Raphaelites. The joy, freshness and sunniness of Raphael is not to be found in their work. Life is painful, puritanic and depressing to them. Old age seems to be upon them, or the decadence of a people that has once been great. Human nature does not need that this strain be put upon it. Life is stronger when more assertive of itself. It has a right to assert itself in defiance of mere rules, and only when it does so is it true and great. The ascetic tone is one of the worst results of a scientific view of the world as applied to literature; for it is thoroughly false both in fact and in sentiment. The strong, hopeful, youthful look at life is the one which literature demands, and because it is the nearest the heart and spirit of life itself. The dead nation produces a dead literature. The age made doubtful by an excess of science produces a literature burdened with sadness and pain. Great and truthful as it may be, it lacks in power to conquer the world. It shows, not the power of Homer, but the power of Lucretius.

Her altruism has its side of truth, but not all of the truth is in it. Any system of thought which sees nothing beyond man is not likely to find that which is most characteristic in man himself. He is to be fathomed, if fathomed at all, by some other line than that of his own experience. If he explains the universe, the universe is also necessary to explain him. Man apart from the supersensuous is as little to be understood as man apart from humanity. He belongs to a Universal Order quite as much as he belongs to the human order. Man may be explained by evolution, but evolution is not to be explained by anything in the nature of man. It requires some larger field of vision to take note of that elemental law. Not less true is it that mind does not come obediently under this method of explanation, that it demands account of how matter is transformed into thought. The law of thought needs to be solved after mind is evolved.

There is occasion for surprise that a mind so acute and logical as George Eliot’s did not perceive that the evolution philosophy has failed to settle any of the greater problems suggested by Kant. The studies of Darwin and Spencer have certainly made it impossible longer to accept Locke’s theory of the origin of all knowledge in individual experience, but they have not in any degree explained the process of thought or the origin of ideas. The gulf between the physiological processes in the brain and thought has not been bridged even by a rope walk. The total disparity of mind and matter resists all efforts to reduce them to one. The utmost which the evolution philosophy has so far done, is to attempt to prove that mind is a function of matter or of the physiological process. This conclusion is as far as possible from being that of the unity of mind and matter.

That man is very ignorant, and that this world ought to demand the greater share of his attention and energies, are propositions every reasonable person is ready to accept. Granted their truth, all that is necessarily true in agnosticism has been arrived at. It is a persistent refusal to see what lies behind outward facts which gives agnosticism all its practical justification. Art itself is a sufficient refutation of the assertion that we know nothing of what lies behind the apparent. That we know something of causes, every person who uses his own mind may be aware. At the same time, the rejection of the doctrine of rights argues obedience to a theory, rather than humble acceptance of the facts of history. That doctrine of rights, so scorned by George Eliot, has wrought most of the great and wholesome social changes of modern times. Her theory of duties can show no historic results whatever.

To separate George Eliot’s theories from her genius it seems impossible to do, but this it is necessary to do in order to give both their proper place. All praise, her work demands on its side where genius is active. It is as a thinker, as a theorizer, she is to be criticised and to be declared wanting. Her work was crippled by her philosophy, or if not crippled, then it was made less strong of limb and vigorous of body by that same philosophy. It is true of her as of Wordsworth, that she grew prosy because she tried to be philosophical. It is true of her as it is not true of him, that her work lacks in the breadth which a large view of the world gives. His was no provincial conception of nature or of man. Hers was so in a most emphatic sense. The philosophy she adopted is not and cannot become the philosophy of more than a small number of persons. In the nature of the case it is doomed to be the faith of a few students and cultured people. It can stir no common life, develop no historic movements, inaugurate no reforms, nor give to life a diviner meaning. Whether it be true or not, — and this need not here be asked, — this social and moral limitation of its power is enough to condemn it for the purposes of literature. In so far as George Eliot’s work is artistic, poetic, moral and human, it is very great, and no word too strong can be said in its praise. It is not too excessive enthusiasm to call her, on the whole, the equal of any novelist. Her genius is commanding and elemental. She has originality, strength of purpose, and a profound insight into character. Yet her work is weakened by its attachment to a narrow theory of life. Her philosophy is transitory in its nature. It cannot hold its own, as developed by her, for any great length of time. It has the elements of its own destruction in itself. The curious may read her for her speculations; the many will read her for her realism, her humanity and her genius. In truth, then, it would have been better if her work had been inspired by great spiritual aims and convictions.

The Ideal.

It was thought that with George Eliot the Novel-with-a-Purpose had really come to be an adequate instrument for the regeneration of humanity. It was understood that Passion only survived to point a moral or provide the materials of an awful tale, while Duty, Kinship, Faith, were so far paramount as to govern Destiny and mould the world. A vague, decided flavour of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity was felt to pervade the moral universe, a chill but seemly halo of Golden Age was seen to play soberly about things in general. And it was with confidence anticipated that those perfect days were on the march when men and women would propose — (from the austerest motives) — by the aid of scientific terminology.

The Real.

To the Sceptic — (an apostate, and an undoubted male) — another view was preferable. He held that George Eliot had carried what he called the ‘Death’s-Head Style’ of art a trifle too far. He read her books in much the same spirit and to much the same purpose that he went to the gymnasium and diverted himself with parallel bars. He detested her technology; her sententiousness revolted while it amused him; and when she put away her puppets and talked of them learnedly and with understanding — instead of letting them explain themselves, as several great novelists have been content to do — he recalled how Wisdom crieth out in the street and no man regardeth her, and perceived that in this case the fault was Wisdom’s own. He accepted with the humility of ignorance, and something of the learner’s gratitude, her woman generally, from Romola down to Mrs. Pullet. But his sense of sex was strong enough to make him deny the possibility in any stage of being of nearly all the governesses in revolt it pleased her to put forward as men; for with very few exceptions he knew they were heroes of the divided skirt. To him Deronda was an incarnation of woman’s rights; Tito an ‘improper female in breeches’; Silas Marner a good, perplexed old maid, of the kind of whom it is said that they have ‘had a disappointment.’ And Lydgate alone had aught of the true male principle about him.

Appreciations.

Epigrams are at best half-truths that look like whole ones. Here is a handful about George Eliot. It has been said of her books — (‘on several occasions’) — that ‘it is doubtful whether they are novels disguised as treatises, or treatises disguised as novels’; that, ‘while less romantic than Euclid’s Elements, they are on the whole a great deal less improving reading’; and that ‘they seem to have been dictated to a plain woman of genius by the ghost of David Hume.’ Herself, too, has been variously described: as ‘An Apotheosis of Pupil-Teachery’; as ‘George Sand

plus

Science and

minus

Sex’; as ‘Pallas with prejudices and a corset’; as ‘the fruit of a caprice of Apollo for the Differential Calculus.’ The comparison of her admirable talent to ‘not the imperial violin but the grand ducal violoncello’ seems suggestive and is not unkind.

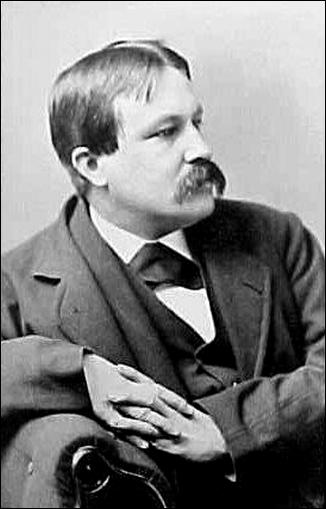

William Dean Howells

– a great admirer of Eliot’s work