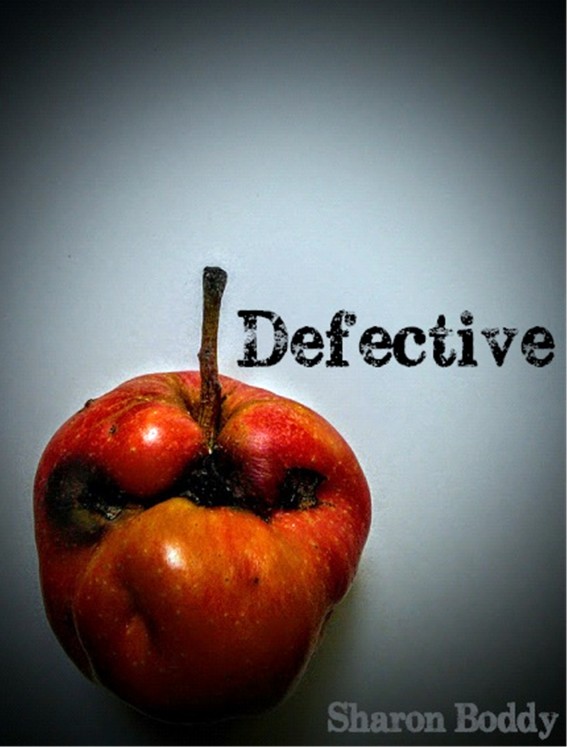

Defective

A novella

Copyright 2015 Sharon Boddy

Published by Sharon Boddy at Smashwords

Smashwords Edition License Notes

Thank you for

downloading this ebook. This book remains the copyrighted property

of the author, and may not be redistributed to others for

commercial or non-commercial purposes. If you enjoyed this book,

please encourage your friends to download their own copy from their

favourite authorized retailer. Thank you for your support.

Table of Contents

The Children

Porkchop, 18

Santa, 17

Titania, 16

Forest, 14

Narrow, 12

Bull, 11

Jones, 7

Jelly, 7

Mixer, 18 months

The Adults

Ma

Pa

The Landlord

PC Pierre

Pater

Rank

Gaines

Mrs. Nibbs

Marvellous

Mrs. Baker

Selected sources from

the reference library of PC Pierre (P), Deloran County

Reference Code:

G32

Title: The Upheaval's

Geologic Legacy, Arthur Pawli, pub. 2417

See summary by PC

Pierre (P), Deloran County, 5.45.22

P3: First came the

vibrations, like something large and heavy falling close by. The

vibrations would have grown stronger and stronger within minutes or

hours and the ground would have begun to shake. Buildings and

infrastructure collapsed, roads were buried. Presumably, many of

the old countries' populations were drowned by buckling rivers,

lakes and oceans; in other places, mountains shook apart, firing

bits into the air. Whole populations — human, animal, insect, bird,

plant — were obliterated in less than a day along with many

important cultural and historical artifacts, now lost to time.

Reference Code: M3

Title: Human Reactions

to Long-term Infection Exposure, Drs. Winj, P., Estelle, F.,

Kathra, R., pub. 2478

See summary by PC

Pierre (P), Deloran County, 11.27.22

P114: In conclusion,

it is not possible to isolate the genetic components of the defect,

previously linked to contaminants unleashed during the Upheaval.

Data suggests that the infection itself, which is no longer fatal,

recurs every thirty to forty years and with each reoccurrence, the

defective gene mutates; however, no two genes studied to date

follow the same mutation pattern. The defect also occurs in

non-infection years but there has been a marked decline in the

number of reported cases in the last twenty years. This could

suggest that its lessening appearance in new births is a signal

that both the infection and the mutation are waning, or that social

or other factors, such as non-reporting behaviours are involved,

which are outside the scope of this study. The majority of the

defects that do appear are minor in nature.

Reference Code:

PR402

Police Crime Summary

Report, Dated: 12.33.42

Reporting Officer: PC

Marsellum Peach

Prisoner Name: Martha

New

Prisoner Number:

F89

Residence: Ferguston,

Deloran County

Charge: Infanticide;

blunt force trauma. Prisoner claims her new born son was defective

and attacked her. CX: Confession.

Reference Code:

PR433

Police Crime Summary

Report, Dated: 1.4.43

Reporting Officer: PC

Marsellum Peach

Prisoner Number:

F89

Notes: Prisoner held

in the local till weather clears and can be transferred to

Andrastyne.

Reference Code:

PR437

Police Crime Summary

Report, Dated: 1.7.43

Reporting Officer: PC

Marsellum Peach

Prisoner Number:

F89

Notes: Prisoner found

dead in cell by hanging. Burial arranged. CX: Morgue.

The first thing Mixer

knew with certainty was that he was hungry. The feeling grew more

intense each day until it became unbearable and Mixer began to lash

out. Quietly, steadily he ate away at his enemy and, in a few

weeks, where there had been two, now there was only one.

"There’s something

wrong with Mixer," Ma said one night in bed.

"There’s something

wrong with all our kids," Pa yawned. He rolled over and looked at

his wife. She looked serious. And old. They kept their voices low;

the children slept above them in the loft.

"This is

different." Ma sat up. "Maybe it’s what you said, that it was

twins."

Ma had been

nervous most of her pregnancy with Mixer, the youngest and ninth of

her and Pa’s kids. Ma said the number nine was bad luck. Nothing

good comes from nines, she would say. Ma said a lot of things like

that and Pa had learned to ignore most of them.

When she was five

months pregnant, Pa listened to her belly and pronounced twins. Ma

wasn’t so sure, but Pa had some experience with this, he said,

pointing to Jelly and Jones, their twins. Ma kept her thoughts to

herself. Either way, she thought, twins or a single, this'll be the

last one. She’d finally perfected the recipe that would see to

that. When Ma’s labour was over, however, only Mixer had shown up.

Pa poked around up there for a bit, perplexed by the absence of

infant. He had distinctly heard two heartbeats.

Pa sat up. The

moon waned in the sky outside their window.

"Different

how?"

Each of their

children possessed at least one defect, although Pa never used that

word. He called them talents. Ma knew them for what they were:

trouble. Anyone different, anyone who could do something others

couldn't was shunned or worse. She and her mother and father had

been kicked out of so many towns when she was a child she couldn't

remember half their names.

Her father had

been a painter but despite his best efforts to keep his defect

under control, his work on barns, houses and fences stood out.

Designs within the paint would appear, faint at first, the outline

of things: trees, women, or the sky at night. The paintings would

then take on deeper lines and colours would appear and disappear.

Her mother had been a healer and had taught her daughter what she

knew of medicine. She would try to help people but they were afraid

of her. They would always be found out and run out of town;

sometimes they were beaten. They moved from place to place and her

parents waited until Ma turned twenty and then left her in Battery.

Alone, they thought, she'd stand a better chance.

She went to work

for the Landlord of Battery, part of a group of young men and women

hired at slave wages to work a pearl apple orchard after the former

owner died. There she met and married her husband and started

having his children. Within a year all the other workers had gone;

the two of them and their growing family had worked the land ever

since.

Her defect was the

ability to see under the earth. She knew what a plant's root system

looked like without ever needing to dig it out. In the early years

at the orchard she often saw things buried among the trees or near

the barn but if she did dig them up, she did it at night when the

children and Hap were asleep. She never told anyone about it. Some

things, like the skeletal remains of a baby buried in the wild rose

bush behind the shed, were best left as they were.

She had been

raised to hate and fear herself and others like her, but most of

all to be afraid of being found out. She couldn't turn back time

but she could make life easier for her children. She could give

them a stable home, keep them safe and protected; few people knew

they were here. She taught them, ruthlessly at times, not to

display their talents, not even to each other. The children were

only allowed to use them for orchard work or when specifically told

to.

Their eldest,

Porkchop was able to see the minutiae of her surroundings at a

glance. She could spot the first sign of life or blight. Her memory

was astonishing and in terms of her daily duties Porkchop's mind

inevitably ran far ahead of everyone else's. Ma sometimes suspected

that Porkchop knew more about how to run the orchard than she did

but her oldest child, besides being sensible and obedient to a

fault, never contradicted any of Ma's decisions.

Forest could

predict the weather. Since he was a baby Forest had been fascinated

by insects and plants and water and how they behaved in different

types of weather. He'd studied their habits and learned that nature

could tell him everything he needed to know so long as he listened

and observed. Forest also had an innate sense of the seasons, how

they would unfold, and what challenges they would bring. He was

indispensable in scheduling some of the most important orchard

tasks.

Ma hated Santa's

talent because she feared what could happen to her if people found

out. Santa could sing. Musicians and singers and artists were among

the most hated of defectives. They didn't do anything useful or

productive; they didn't grow food or catch fish or trap animals.

They didn't fell timber or plant trees; they didn't build things or

fix things.

Bull had always

been large for his age. He could track even the smallest game from

miles away. Ma believed that her son's keen sense of smell came

from her being bitten by a stray dog when she was pregnant with

him. It wasn't unusual for feral curs to stray onto the property in

those days. Their numbers dropped dramatically after they began

feasting too much on the local deer population and the Landlord

thought it would be both fun and useful to institute a dog-killing

contest. The tenant farmer who killed the most dogs got double his

salary for the month. Pa never won. The contest ran for six years

until the dogs had been almost wiped out.

Narrow was worse

than her husband for taking things apart but, unlike her husband,

her middle child put things back together again. When he was about

nine months old he woke up the household taking apart his crib. The

slats had given way and he'd gone straight down, landing on his

bottom. When Pa brought his tool box to fix the crib the next day,

Narrow had crawled over to the box, rummaged for a moment and

brought out a screwdriver. Narrow could almost always fix or build

or create anything with whatever resources were available.

Titania was Ma's

special daughter.

Twins were

sometimes considered defective simply because they were twins. Most

people did accept that twins existed naturally in nature, but

identical girl-boy twins, like Jelly and Jones, were unusual and

therefore highly suspicious. They were so alike that it wasn't

until their hair began to grow that Ma began to cut her son's but

not her daughter's hair so that she could tell them apart.

Jones never

learned to crawl. One day, as he sat cross legged on the floor of

the press house he had hopped across the room. Ma had been standing

at the pressers, enormous square wooden boxes with tight wire

mesh-topped lids that were pressed down onto the pearl apple mash.

The juice flowed through the boxes into a trough that was connected

to a pipe to the fermentation vat. She thought she had closed the

press house door but she'd suddenly felt a breeze by her ankles.

She looked around and found Jones in one corner, gnawing on his

thumbnail. He hopped back to where he'd been. She'd seen a blur

across her vision and her son then reappear on the other side of

the room.

Jelly had learned

to talk early. At six months she was able to tell her mother, in a

few words, what she needed, a diaper change or food. Her defect

deepened the day she found a plastic bag caught in one of the pearl

apple trees in the orchard. The bags were useful things if they

didn’t have many holes in them, but their numbers had dwindled with

each passing year.

Ma was teaching

Jelly to forage for medicinal and edible plants and had taken the

four-year old into the woods one autumn day for another lesson.

Jelly had the right temperament for it. Patient. Observant.

Curious.

On their return

home, the press house and barns in the distance, Jelly caught sight

of the bag. She carefully untangled it and smoothed it out on the

ground.

"Made in China,"

she said.

"Stop messing

about with that," said Ma impatiently. She needed to start supper;

needed to make sure that Santa started supper.

Jelly continued to

study the bag. It had a line of black marks on it.

"That’s what it

says. Made in China."