Decoding Love (27 page)

Authors: Andrew Trees

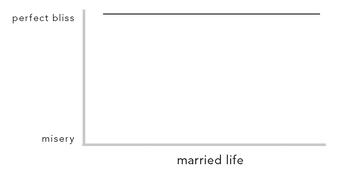

One place we might look for answers is arranged marriages. Earlier, I cited a study of Indian arranged marriages, which found that those marriages were happier over time than Western marriages. Orthodox Jews who use a matchmaker have reported similar experiences of love continuing to grow after marriage. If we are willing to loosen our grip on the romantic story line, we might just find that our ideas about the course of love and marriage are out of whack. Right now, our ideal image of marriage looks something like this:

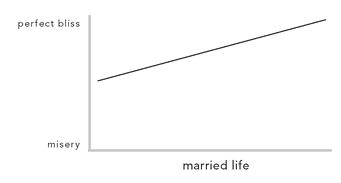

We are supposed to be ecstatic on our wedding day and also live happily ever after. Does that look remotely realistic to anyone? Yet that is the rough outline of most pop culture presentations of the romantic story line. Now, let’s look at a graph at what love looks like for arranged marriages:

Doesn’t that seem both more realistic and, ultimately, a far healthier outlook for long-term happiness?

What I’m saying strikes at the core of the romantic story line and at some of our most cherished myths about love and marriage. But the research is there to back it up. Take, for example, the PAIR Project run by Ted Huston at the University of Texas at Austin. Launched back in 1981, the project has followed 168 newlyweds, studying everything from their early courtship to the eventual success or failure of the relationship. His work is unusually revealing because it looks at couples much earlier in their relationship and for a much longer period of time than virtually any other study. And what Huston and his fellow researchers have discovered challenges many of the central elements of the romantic story line.

Let’s start with the idea that you should marry someone you are madly in love with. Who hasn’t attended a wedding where the couple seems completely enamored with each other and thought, I hope I find a love like that. It turns out that our envy of those blissful couples is entirely misplaced. They are more likely to get divorced because those feelings of romantic ecstasy are impossible to maintain (less surprisingly, the PAIR project also found that couples who have a brief courtship are more vulnerable to divorce and that many newlyweds are not blissfully in love when they marry).

This is only one of a number of surprising findings. For example, it turns out that even large differences in taste are not important to the success of a marriage—

unless

you brood about them. Brooding, they found, leads to divorce. And conflict itself is not a sign of trouble; instead, the key for couples is to preserve positive feelings for each other. Loss of affection, not conflict, is the great predictor of divorce. Even longevity is not necessarily an indication of success. Huston has found that some couples have lackluster relationships but do not divorce. They basically accept that married life is a source of modest dissatisfaction.

unless

you brood about them. Brooding, they found, leads to divorce. And conflict itself is not a sign of trouble; instead, the key for couples is to preserve positive feelings for each other. Loss of affection, not conflict, is the great predictor of divorce. Even longevity is not necessarily an indication of success. Huston has found that some couples have lackluster relationships but do not divorce. They basically accept that married life is a source of modest dissatisfaction.

The PAIR project does offer support for some folk wisdom. For example, women should trust their intuition. Women in the study who feared that the marriage might have future problems generally discovered that their fears were well founded. You also don’t have to hang around for years to see if the marriage will improve. According to Huston, the first two years tend to reveal whether or not you are going to be happy. And forget about having a baby to solve your problems. The birth of a child does not change how a couple feels about each other. The project also confirms what numerous other studies have suggested—men with feminine traits make better husbands.

I know what you are thinking. You would never fall into any of these traps. You are too savvy. You probably feel that you can just look at a couple and predict with great accuracy whether or not they will stay together. Well, I’m here to tell you that you are deluded, at least according to a study by Rachel Ebling and Robert Levenson. The two researchers showed people three-minute videotapes of five couples who stayed married and five couples who got divorced and then asked the viewers to make predictions about those couples. Most people were terrible at predicting which couples would get divorced and scored at a level only 4 percent above random chance. In this instance, women’s intuition also proved to be no help. The study found that women were no better at predicting than men. And in a stunning confirmation of body language over spoken language, the researchers found that listening to the actual content of the conversations made for less accurate predictions. But the scary part is what Ebling and Levenson found when they gave the same test to trained professionals, such as therapists. It turned out that the pros were just as bad at figuring out what would happen to the couples as the ordinary people and scored no better than if they had randomly guessed.

Married couples who are feeling smug about how well they know their partners should also take stock. According to another study, the longer couples were married to each other, the worse they became at reading each other’s minds. They also became more confident over time in their ability to guess what their partner was thinking. In other words, they were getting more confident in their predictions at the same time that their predictions were getting less accurate. The reason for this failure of marital communication was that the longer a couple was married, the less attention they paid to each other. For any theory of marriage predicated on good communication, the study reveals just how daunting that task can be.

While you or I may not be very good at predicting whether or not a couple has the right stuff or even what our partner is thinking, there is someone who is very good at it—John Gottman, a psychologist at the University of Washington. He runs the Gottman Institute, which has been affectionately dubbed “the love lab.” Gottman has been studying couples and trying to understand why they succeed and fail since the 1970s. To do this, he has come up with a method of analysis that is probably the most rigorous attempt to decode marital interactions ever invented. Typically, he will videotape a couple while they discuss something about which they disagree. That in itself is nothing special. What sets Gottman apart is his method of analysis. He and his researchers then break down the tape for both content and affect. He has developed an elaborate scoring system that covers virtually every emotion a couple might express. Each fleeting emotional tic is scored so that a few seconds’ exchange will result in several notations for each person. The love lab also adds another layer of data—the couples are hooked up to heart monitors as well as other biofeedback equipment to measure people’s stress levels during the conversation. To give you some idea of how rigorous and exhaustive this method is, Gottman estimates that it takes twenty-eight hours to analyze a single hour of videotape.

What all this painstaking analysis offers is a level of precision unequalled by anyone else studying marriage. Gottman’s methods are incredibly good at determining which couples will succeed and which will fail. How good? If he analyzes an hour-long conversation, he can predict with 95 percent accuracy if a couple will still be married fifteen years later. Needless to say, after years of practice, Gottman has become spectacularly good at seeing what most of us miss. He understands relationships in the way that Tiger Woods plays golf—with a kind of effortless grasp that makes the rest of us look inept.

We can’t all be John Gottman, but we can use the insights that he has developed. For those in a relationship who want to know whether their partnership will succeed or fail

right now

, Gottman has outlined a number of patterns that can help reveal whether or not newlyweds will get divorced, which he can identify based on watching the couple for only three minutes. The first crucial element is how the discussion starts. Women usually are the ones to open the conversation (one reason why the words a man most fears to hear are, “We need to talk”), and they establish the tone of the exchange. The question is, does the woman begin with a harsh or a soft opening? That will determine much of what follows. Second, does the woman complain about something specific (I wish you would take the garbage out) or something global and character related (You are so lazy—you can’t even bother to take the garbage out). If a couple can master the soft opening and the specific complaint, they will be a long way toward a happy marriage. The partner’s reaction to all of this is also crucial. Is he open to his wife’s influence? Yes, it’s true—listening to your wife is incredibly important for a happy marriage. Does his response amplify over time (in other words, does he stay calm or get angry)? And does he get defensive, which will make him reject his wife’s influence and likely get more angry? If the husband tends to get defensive, the couple also has a higher chance of divorce. There—success or failure in three minutes or less.

right now

, Gottman has outlined a number of patterns that can help reveal whether or not newlyweds will get divorced, which he can identify based on watching the couple for only three minutes. The first crucial element is how the discussion starts. Women usually are the ones to open the conversation (one reason why the words a man most fears to hear are, “We need to talk”), and they establish the tone of the exchange. The question is, does the woman begin with a harsh or a soft opening? That will determine much of what follows. Second, does the woman complain about something specific (I wish you would take the garbage out) or something global and character related (You are so lazy—you can’t even bother to take the garbage out). If a couple can master the soft opening and the specific complaint, they will be a long way toward a happy marriage. The partner’s reaction to all of this is also crucial. Is he open to his wife’s influence? Yes, it’s true—listening to your wife is incredibly important for a happy marriage. Does his response amplify over time (in other words, does he stay calm or get angry)? And does he get defensive, which will make him reject his wife’s influence and likely get more angry? If the husband tends to get defensive, the couple also has a higher chance of divorce. There—success or failure in three minutes or less.

Unfortunately, even in the cause of scientific inquiry, married couples are reluctant to put their squabbles on display for an importunate author like myself, so I have had to turn to a different source for my marital spats. In contrast to the other chapters, my examples here are not drawn from real life but from literature, and I believe I have discovered an exemplary couple when it comes to illustrating Gottman’s principles of communication in a happy marriage: P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster. Let’s take an illustrative case from “Jeeves and the Unbidden Guest.”

JEEVES: Pardon me, sir, but not that tie.WOOSTER: Eh?JEEVES: Not that tie with the heather-mixture lounge, sir.Notice the soft opening of Jeeves.WOOSTER: What’s wrong with this tie? I’ve seen you give it a nasty look before. Speak out like a man! What’s the matter with it?Wooster responds with exactly the sort of defensiveness that Gottman warns against.JEEVES: Too ornate, sir.Again, Jeeves is an exemplar of restraint. His criticism of the tie is specific, and his criticism never becomes a general critique of Wooster’s character.WOOSTER: Nonsense! A cheerful pink. Nothing more.Still defensive, although hardly amplifying the conflict.JEEVES: Unsuitable, sir.WOOSTER: Jeeves, this is the tie I wear!Wooster remains impervious to his wife’s, I mean his valet’s, influence.JEEVES: Very good, sir.Jeeves is intelligent enough not to push the argument to any sort of breaking point. After a number of pages of hijinks on the part of Wooster and sagacity on the part of Jeeves, we return again to the tie.WOOSTER: Jeeves!JEEVES: Sir?WOOSTER: That pink tie.JEEVES: Yes sir?WOOSTER: Burn it.Ultimately, Wooster overcomes his defensiveness and accepts Jeeves’s influence on the all-important subject of the proper fashionable attire for a gentleman, a model of marital communication that aids their sturdy partnership through many a tight spot.

Other books

Masked by Norah McClintock

DrillingDownDeep by Angela Claire

Everyone's Dirty Little Secrets by Miles, Matthew

Rebel Temptress (Historical Romance) by Constance O'Banyon

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

The Grace Series (Book 3): Dark Grace by M. Lauryl Lewis

Truth Or Dare by Lori Foster

Sweet Convictions by Elizabeth, C.

Njal's Saga by Anonymous