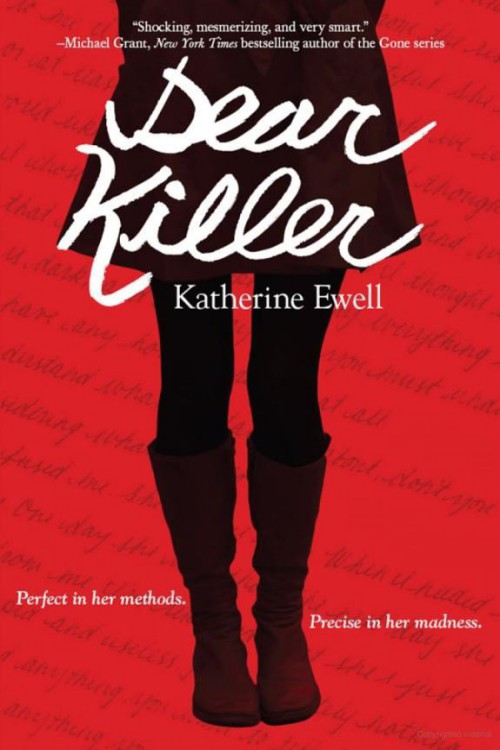

Dear Killer

Authors: Katherine Ewell

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #Violence, #Law & Crime, #Values & Virtues

Katherine Tegen Books is an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Dear Killer

Copyright © 2014 by Katherine Ewell

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

www.epicreads.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ewell, Katherine.

Dear killer / Katherine Ewell. — First edition.

pages cm

Summary: “Kit, a seventeen-year-old moral nihilist serial killer, chooses who to kill based on anonymous letters left in a secret mailbox, while simultaneously maintaining a close relationship with the young detective in charge of the murder cases”—Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-06-225780-2 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-06-232862-5 (international edition)

EPUB Edition JANUARY 2014 ISBN 9780062257826

[1. Serial murderers—Fiction. 2. Murder—Fiction. 3. Interpersonal relations—Fiction. 4. Schools—Fiction. 5. Letters—Fiction. 6. London (England)—Fiction. 7. England—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.E94716De 2014

2013005072

[Fic]—dc23

CIP

AC

14 15 16 17 18 LP/RRDH 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FIRST EDITION

For my parents,

who are nothing like the parents in this book

R

ule one.

Nothing is right, nothing is wrong.

That is the most important guideline, and the hardest one for most people to understand—but I have understood it my entire life, from the moment I laid my hands on that first victim’s neck to this very moment as I think about the blood under my fingernails and the body I have so recently left behind. Nothing is right and nothing is wrong. For some people a thing may be right, and for others it may be wrong. There is no greater truth to morality—it is merely an opinion.

I don’t crave death. I’ve heard of serial killers who love it, who live for the moment when their victim stops breathing, who thrive on it. I am not like that. I kill as a matter of habit and as a consequence of the way I was raised. I could walk away from the killing and never look back.

But I won’t walk away, not now. My faith in my way of life has been tested. I have doubted myself. But I have overcome my doubt.

My name is Kit, but most people know me as the Perfect Killer.

I kill on order. I am everyone’s assassin. I belong to no one but the grim reaper herself.

I checked my mail on a late-summer Sunday. School had just come back into session. It was afternoon, the cool kind of afternoon when it’s too warm for a sweater and too cold for bare arms. The irritating kind of afternoon. But really, I didn’t mind the weather too much. It’s hard to mind something when you know you’re going to get paid soon.

As I walked along the sidewalk, I imagined I was looking at myself from the outside, from the perspective of the strangers I was passing. They would see a girl of average to tall height, a girl who was teenaged, brown eyed, blond, fairly pretty but not memorable; they would see a girl dressed neatly and casually, with a pair of jeans that was wearing thin a bit at the knees, a silver Tiffany bracelet the sole indication of her family’s modest wealth. They would see dark eyes under dark eyelashes, prominent collarbones, and a smattering of freckles dashed across a thin nose like Audrey Hepburn’s, the only truly beautiful feature of a small pale face—would they see a seventeen-year-old murderer?

No. They wouldn’t. No one would.

I didn’t chv death, but I did love my secrecy. It made me feel like a superhero, sort of. A double life. One life average and easily passed over, the other famous. And I

was

famous. I was London’s most famous killer since Jack the Ripper, had been for years, and I loved it.

I was suddenly called back into memory. Eight years before, when I was nine. I remembered it well, remembered his staring marble eyes and the bruises I left on his neck—

Before me, the mailbox had belonged to my mother. She had been the one to begin things. In her day, she hadn’t been like me. She had longed for murder, needed it somehow, seen a dire need for her unique morality in the world, felt bloodlust. Murder had always been more of a job to me than a calling. But of course, like me, she wasn’t stupid. She was sensible enough to not allow herself to be caught.

Eventually things had gotten too unsteady, she told me through offhand comments and casual snippets—she had gotten too close to being identified. She was never really suspected by anyone, though. Every time she told the story, she made a point of telling me that much; she had gotten close to being suspected, but not too close. She had stopped to keep herself safe.

She had settled down, started a family. Married a man who had been carefully chosen to be ignorant, busy, and emotionally distant. Carefully chosen, so he wouldn’t realize what she was and what I would become. Because even after she stopped killing, even after the end, the longing for murder still itched at her—she still needed death, needed to know that someone was carrying out her work. So she trained me. She made me a murderer in her place; she lived through me. I have carried on her legacy.

In time, her mailbox became mine. When I was nine, we began to manage it together, and when I was twelve, she let me have it all for my own. I only killed four between the ages of nine and twelve, but when I took absolute possession of the mailbox, I set a quicker pace—about ten a year. Sometimes there were more, sometimes less, sometimes a few in the span of a few weeks and sometimes no kills for months—but that was my general guideline.

And like my mother, I found my trademark. She drew hearts in Sharpie on her victims’ chests, though she was a much less prolific murderer than me. She had never achieved my fame. The Perfect Killer—there’s not a person in London who doesn’t know and fear that name nowadays.

And what a name, too! The media, who coined it, do love their sensationalism. I can’t say that I dislike it, or that it’s inaccurate. As far as monikers go, I think I’ve done pretty well for myself.

I’m not alone in my talent, though. I saw a picture of a murder of my mother’s once, and even though she was never famous, I had to admire her prowess, her precision. The murder was exquisite. The picture I had seen had been of a young female, neck broken perfectly against the corner of a table, splayed out halfway on the floor, halfway on a chair, her shirt torn open and a cartoonish heart drawn neatly in black on her skin. My mother had pushed the pen down so hard that the skin was bruised blue and green around it.

It surprised me to know that she had once been so powerful.

My own trademark was probably the main reason for my fame. I left my mail behind.

I walked down King’s Road, pretending to admire clothing in windows and ponder going into small cafés I passed without actually considering going in. I made my way slowly and calmly toward my destination, not drawing attention, blending into the scenery like a chameleon. I was invisible. No one would notice me.

I stopped and gazed through the window of a friendly-looking café called the Brass Feather. It was new. The building, of course, had been there for a long, long time, longer than most people knew, but the café had only recently come into business, after the one that had been there before went out of business. The new owners had totally redone the decor. But they had left the bathroom alone.

That was tradition—and superstition.

No matter how many times the shop was sold and bought, the women’s bathroom stayed the same. The same and incredibly secret. Strangely few people knew about it, considering the fact that I was so famous. Not even the police knew about it. Or at least I assumed so, since they hadn’t taken control of or searched it yet. And that was what the police

did

for these sorts of things. They were very crude in their customs.

I smiled and walked inside. The walls, painted in a pale brown color like sandy dirt, felt warm and comfortable. My boots clicked against the wooden floor. It was all very pleasant. People talked at nearby tables, chattering and laughing, or read the newspaper, or texted or talked or played games on their phones. Bland, generic music came quietly through the speakers. But a small note, written on printer paper, was hung in the back of the room, next to the bathroom door, looking out of place, reminding everyone always of the darkness that resided here. I knew what it said. I had been here before. I liked that note. It reminded people of the superstition surrounding the shop, in case they forgot. The dark superstition—the superstition that wasn’t entirely false. Or even remotely false, really.

I headed for the counter, running my eyes over the selection of pastries in the glass case in front of me. The bored-looking teenage boy behind the counter stared at me insipidly as I considered, his green eyes flat and uninterested.

“What do you want?” he asked, as if I were insulting him personally in some way.

I ordered Earl Grey tea and carrot cake, and he gave them to me.

“Eleven sixty,” he said. I handed the money over, he gave me change, and I headed toward a table in the middle of the room. I sat down and started at my cake cheerfully, biding my time. I would check my mail after I was done, and then I would leave.

I watched the people entering and exiting the bathroom carefully, marking their entrances and exits in my mind, smelling the scent of sugar and coffee in the air; the smells were pleasant together, even though I had never much been one for coffee.

I would have to be the only one in the bathroom in order to do my work. I ate slowly, carefully, innocently. My senses were sharp. I waited. I would have to be clever about it.

I took a sip of my tea and realized I was done with it. My cake, too, was nearly gone. The woman who had been in the bathroom came out, dark hair swishing; it was empty now. Now was as good a time as any. I swallowed the rest of my cake, tasting the strange sweetness of carrots and cream cheese, and stood, strolling toward the bathroom, glancing at the sign next to the door as I came closer and could read it.

REQUESTS TAKEN INSIDE

, it read in sharp, insistent letters with angles like blades. Not my own words. Someone else, a believer, had written that, but I appreciated it. Beneath the words was a sketch of a postcard, with scribbles where the writing should be. A generic postcard. As if anyone could fill in the blanks where the scribbles were and file their own request.

Well, that

was

generally how it worked.

I didn’t have the time to grant them all, of course. I had school. And if I killed too often, I would inevitably call too much attention to myself. I was famous in London, but I didn’t want to be a worldwide criminal—that would mean too many people on my tail, and too much danger, even for me. But I tried to fulfill as many requests as I could. My clients repaid me with money and with secrecy. None who had their requests filled, even those tracked down and interrogated by the police, ever confessed the location of my mailbox. The mailbox set a strange spell of silence over them. The police didn’t know of that secret place, and I was glad of it.

As I had predicted, the bathroom was empty. The yellowed white tiles on the walls that cracked like spiderwebs at the edges, the ones that hadn’t been changed since the forties, were covered in graffiti. Outside, in the restaurant, they might be able to mostly deny the legend that lived in their shop, but in the bathroom there were no secrets. I traced my fingers across the graffiti on the walls, satisfied, trailing them along the curls of the

G

s and the straightness of the

T

s.

“The devil lives here,” one read. “Thank God for angels,” read another. “He saved me.” That irritated me a bit—everyone automatically assumed I was a man. This was the

women’s

bathroom, wasn’t it? “My wish was granted.” “The killer didn’t listen.” “This place is a joke, nothing but a stupid urban legend.” “Don’t tell.” “Death will come to the unworthy.”

I slipped into the third stall and locked the door behind me. The large tile above the toilet was loose, like it always had been.

I didn’t have to use gloves to check my mail, really, because there were so many fingerprints on the tiles that individual fingerprints were hard to identify, but I put them on anyway, the latex making my hands feel sticky. I pried the tile out of the wall and set it down across the toilet seat. I stared into the small compartment behind the tile that had been built into the wall so many years ago, and smiled.

I checked my mail only about once every two months. Since I had last come, a lot of people had made requests. Letters nearly filled the mailbox, at least thirty of them. They were stacked on top of one another, money paper-clipped to some and inside the envelopes of others. My fee. I opened my bag and, trying to be quiet, picked up a handful of letters and slid them inside, sandwiched between my wallet and a notebook. Then another handful, the paper rustling between my fingers with a sound like bird wings.

I heard the sound of clicking heels outside the bathroom door, moving toward me. I cursed under my breath and moved faster, trying not to drop any of my letters. Even though the door was locked, the sound of paper would be easily heard. I put handful after handful into my bag, tense and quiet, biting my lip hard until I almost drew blood and lightened my bite. The heels clicked into the bathroom.

I flushed the toilet to conceal the noise and stuffed the last few letters into my bag, zipping it shut, wedged the tile back into place, and exited the stall as I slipped off my latex gloves and stuffed them neatly into my jeans pocket. I dipped my hands under a faucet, just for show, the coldness of the water surprising me. I left the bathroom quickly. That was too close. Of course, there was nothing I could have done about it. But it was too damn close. At least I had gotten away. I had good luck, I supposed. Always had. I walked through the café and toward the street, forcing myself to act casual. The boy at the counter looked at me vaguely.

After a few moments of walking down King’s Road toward home, I relaxed. In the end, nothing had happened. I had my letters and my money, and no one had seen me. Like always. Things were always the same, and always would be.

I would read my letters tonight.