David Waddington Memoirs (9 page)

Read David Waddington Memoirs Online

Authors: David Waddington

While still a pretty new MP I had a brush with General Gowon, the ruler of Nigeria – then engaged in a bloody war against secessionist Biafra. I was sufficiently naive to write a personal letter to the General enclosing a letter from a constituent complaining about the many atrocities perpetrated in the war; and, to my

astonishment

, received a personal letter back from the General in which he berated me in most intemperate language for daring to interfere with the domestic affairs of Nigeria. The General cannot have had much to do with his time.

I also had an interesting encounter with Robert Maxwell which perhaps sheds some light on that extraordinary character. He was chairman of the catering committee in the House of Commons and already showing signs of megalomania. In those days I was writing a regular column for my local newspaper and, running out of anything to say, I put in a few lines about the poor food in the House of Commons. I had no reason to believe that the great Maxwell was an avid reader of the

Nelson Leader

and I was surprised when a few days later I received a letter from him in which he complained at my lack of courtesy in not telling him of my concerns about the food in the Palace of Westminster before rushing to the press.

One of the truly memorable occasions during the run-up to the 1970 general election was Bernadette Devlin’s arrival in Parliament after she had won Mid Ulster in a by-election. On 22 April 1969, and within an hour of taking her seat, she made her maiden speech and, although it was full of monstrous nonsense, the fluency, command of language and complete self-possession of this 21-

year-old

left everyone spellbound. The Reverend Ian Paisley then made his contribution and a wit remarked that it was the only speech delivered on the floor of the House of Commons which could be heard distinctly on the floor of the House of Lords.

In 1968 the government had introduced the Parliament (No. 2) Bill which would have allowed existing hereditary peers, but not their successors, the right to attend the House of Lords but not to vote, and would have created a House of voting peers based exclusively on patronage. Left wingers in the Labour Party joined forces with right wingers in the Tory Party led by Enoch Powell to defeat the measure, both factions believing that the scheme, supported by both front benches, would weaken still further the very few constitutional checks on abuse of power by the Executive.

It was a splendid opportunity for a new Member. I supported the rebels and gloried in the discomfiture of the government. Eventually the government abandoned the measure, using as an excuse the need to introduce urgent legislation to penalise

unofficial

strikers and bring some semblance of order into the ever more chaotic industrial relations scene. Eventually this measure was also abandoned, largely as a result of Jim Callaghan’s decision to side with the TUC against Barbara Castle’s modest attempt at reform. Callaghan was later alleged to have stated that the key to success for a Labour government was to find out what the trade unions wanted and give it to them; and certainly he practised in the late 1960s what he later preached.

In January 1969 I went on a trip to North Africa sponsored by the Ariel Foundation. My travelling companions were Keith Speed, Peter Archer and David Marquand. Algiers was shabby. The

flowers

which used to decorate the centre of the city were no more. The government was building an enormous steel mill with Russian money but had no idea as to who would want the steel when they had made it. Tunisia, with a far more successful economy, was dull – apart from our meeting with President Bourguiba who showed us numerous photographs of people he said were friends shot by the French in the fight for freedom. We were impressed with Libya which had suddenly become enormously rich following the

discovery of oil, but we did not fully appreciate how the reforms aimed at bringing the country into the twentieth century were also releasing other forces. It had been decided to move Parliament to the green hills of Cyrenaica, King Idris’s homeland. The

parliamentarians

were to sleep in long barrack rooms on army-style beds. We arrived on a Saturday; the parliamentarians were coming on Monday to start their labours on Tuesday and already at the foot of each bed were laid out two neatly folded blankets, a mess tin with knife, fork and spoon and a chunk of bread for their first breakfast.

We travelled across the border into Egypt and as we approached Cairo there were bunkers along the side of the road housing Russian MIG jets. We visited some of the fifteen ships trapped in the Great Bitter Lake since the Six-Day War, and we went up to Aswan and saw the dam being built.

I cannot pretend that all parliamentary trips are educational but this one certainly was; and it certainly broadens one’s mind getting to know Members on the other side of the House.

In January 1970 I joined the board of J. B. Broadley Ltd, makers of leather cloths and coated fabrics in Rossendale Valley. This was at the invitation of Michael Jackson, who died a few years later after the firm was taken over by Ozalid. He was a good man and a very good businessman, and I am very grateful for the opportunity I had to learn at his feet. I also went on the board of Wolstenholme Bronze Powders Ltd. – later renamed Wolstenholme Rink Ltd. – a firm of which John Wolstenhome (goalie for Bury football club as well as a businessman and Gilly’s grandfather) was co-founder. I think all this broadened my experience and made me a rather better MP than I would otherwise have been.

In 1969 James went away to school, to Aysgarth in North Yorkshire. The poor boy hated going and for many months before leaving home used to get into our bed in the early morning and beg to be allowed to stay with us. Once he said: ‘If you let me stay, I’ll do

all the housework and the cooking.’ We felt dreadful, particularly when I myself had been so homesick, but we also felt we had to grit our teeth and do it for his sake. If he had stayed at home he would have been the only one of his friends not going away to school. The awful day came when we motored over to Aysgarth and left him there but the next day the headmaster, Simon Reynolds, telephoned to say he had settled in well. However, James’s own letters did not bear this out, and for the first few years he suffered greatly. Matthew went to Aysgarth a year-and-a-half later and, although in constant trouble, loved school right from the start. While Matthew thrived, James lamented and after nearly two years at school wrote:

I hope you are well; I’m not. I hate it here and besides last night I could not get to sleep until half past one and woke up at five to six. Please, please do something about it. I won’t say anything about this in my Sunday letter because I don’t want a master to see it. Please again do something and please send a nice parcel. From JAMES.

Matthew on the other hand wrote:

On Wednesday we had great fun because it was a power cut. On Tuesday we saw the film

Demetrius and the Gladiators

. It was a good film because it showed gladiators fighting and other

spectacular

things. The Emperor in the end got killed and I think it served him right. He was a stupid person.

In the early summer of 1970 Harold Wilson called a general election. He did so after the Labour government had got up to a monstrous piece of trickery. The Parliamentary Boundary Commission had reported and by law the government had to present to Parliament for approval the order implementing its proposals for changes to

constituency boundaries. The report was not to Labour’s liking so, while complying with the law by presenting to Parliament the order, they then whipped the Parliamentary Party to vote the order down. As a result, the election was to be fought on the old

boundaries

giving Labour an advantage they did not deserve.

Gilly became ill with glandular fever and was unable to take part in much of the campaign. It went well enough from my point of view although, according to the polls, we did not seem to be making much headway nationally. But on the last morning a more encouraging poll was published and in Nelson & Colne we felt we would be all right. We were – just. The result was:

D. Waddington (Conservative) 19,881

E. D. Hoyle (Labour) 18,471

Conservative majority 1,410

The Party was back in office with a perfectly adequate majority of thirty-one seats.

W

hat set the tone for the new parliament was the fact that the Labour Party had expected to win and felt that it had been cheated of the victory it had deserved. Usually in British politics a party which loses an election after a period in office is pretty demoralised. Its members accept that they would not have lost had they not made mistakes but that their defeat does at least give them the opportunity for new thinking. This was not the mood of the Labour Party in 1970. It did not see the need for new thinking, and it was going to make sure that Ted Heath had no honeymoon. Sometimes its attacks seemed pretty trivial. I remember in particular the synthetic anger when in the summer of 1970 the Minister for Posts, Chris Chataway, found a new chairman for the Post Office. And Labour supported every bit of industrial unrest in the country, hoping that strike after strike would show the country that the Conservatives could not govern.

The government suffered from some real ill luck. It was certainly a terrible blow when only just over a month after the election Iain Macleod, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, died; and then came events which scuppered the government's promise not to feather-bed industry and aid lame ducks. It was bad enough when Upper Clyde Shipbuilders ran into difficulties and had to be rescued, but the Rolls-Royce affair was even more damaging.

Rolls-Royce found itself in financial difficulties after entering

into an unwise fixed price contract for the provision of the RB 211 engine for the Lockheed TriStar, and the government had to nationalise the aerospace division of the company. It was not only a major crisis: it made us a laughing stock, with John Davies as Secretary of State for Industry quite unable to make a convincing case for what was being done. Then came the Leila Khaled affair and the government, which had been elected to pursue a tough law-and-order policy, cut a sorry figure when the hijacker of an El Al plane was allowed to go free in exchange, it seemed, for the release of the passengers of another plane hijacked by Arab terrorists in Jordan.

In the general election campaign Ted Heath had sought a mandate to negotiate terms for Britain's entry into the EEC and first Tony Barber then Geoffrey Rippon were given the job of

negotiating

. In July 1971 a White Paper was published setting out the terms agreed, and there then followed a most brilliant exercise in business management and whipping by Francis Pym. He persuaded the Prime Minister that in the six-day debate on the principle of entry the Conservative Party should have a free vote. Without a whip it was likely that more Conservatives would vote against the motion approving entry than would do so if there was a whip, but he believed, and he was proved right, that if the Tories were not whipped, far more pro-Europeans in the Labour ranks would vote for the motion. The motion was carried by 356 votes to 244 with thirty-nine Conservatives voting against the motion and two abstaining, and sixty-nine Labour members voting for the motion and twenty abstaining. Getting a second reading for the Bill proved far more difficult and it is doubtful whether it could have been done had the Prime Minister not made the division a vote of confidence, saying that if the vote went against the government he and the whole Cabinet would resign. The closing stages of the debate were a nerve-wracking business. With the Prime Minister declaring that

if the vote went against the Bill âthis Parliament cannot sensibly continue', a second reading was obtained by just 309 votes to 301.

In October the Conservative Party Conference had voted

decisively

for EEC entry. I was unhappy because of what seemed to me the betrayal of the Commonwealth, and New Zealand in particular, through our having to adopt the common agricultural policy; but I could see the importance of trade with Europe for British

industry

and although the Commission's supranational ambitions were already evident, I thought we and other countries would together tame the beast. I certainly did not think that we would finish up with the undemocratic mess which is today's EU.

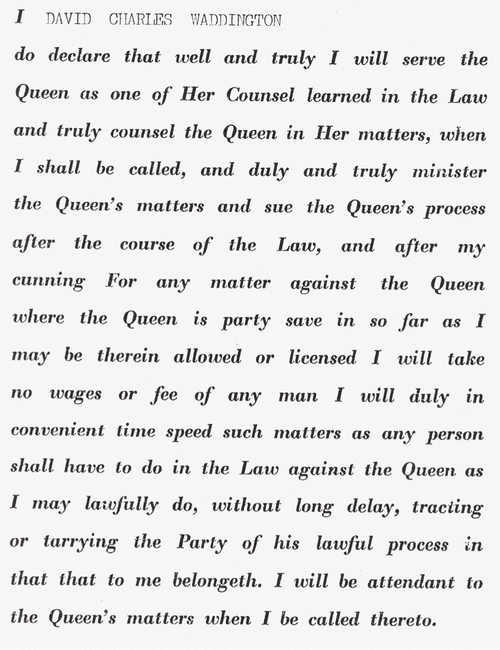

QC's Oath

At the beginning of the parliament, Attorney-General Peter Rawlinson had asked me to be his Parliamentary Private Secretary, and I accepted. There is nothing very glamorous in being a PPS, but it was considered the first step on the ladder. I also decided to apply for silk (to become a Queen's Counsel) because travelling back to Manchester night after night after voting in the House and then, after a hard day in court, getting back to London for another vote was proving a great strain.

My application was successful, and the declaration which one then had to make was truly extraordinary; reading it was a

challenge

because of the absence of punctuation marks.

I had not been well since Christmas 1970 but soon after all this I began to feel really ill. I went to hospital, where it was at first thought I had a brain tumour, but then after a series of tests encephalitis was diagnosed. This then led to epileptic fits. On one occasion I passed out in the House of Commons and came to in Westminster Hospital. On another occasion I passed out in the Lyons snack bar on Bridge Street and again woke up in hospital, this time with a large cut on my forehead. It was an incident which had an odd sequel. Years later I received a letter from a man who said that he was disgusted at my discourtesy in never having

written

to him to thank him for coming to my rescue when I had been taken ill in Westminster. He had ruined his shirt in doing so and wanted £5 for a new one. I, of course, had no idea who had looked after me and certainly had no knowledge of a shirt ruined by my blood. But I had no reason to doubt his word and he got his money.

One Friday morning when I arrived back in Manchester off the night sleeper I discovered that my car had been stolen from the car park. I walked to the bus station, caught a bus to Accrington and then another one to Whalley, getting off at a call box on the way from where I intended to phone Gilly. But having got in the box I could not remember our number and when I started

looking in the phone book I could not remember what my name looked like in print. I walked to a shop and I asked the surprised man to look up my telephone number for me and ring my home, which he duly did and Gilly came to the rescue. All this was followed by another spell in hospital, but eventually things came right, and the only lesson to be learned is: don't get encephalitis. It tends to lead to tasteless jokes about swollen headedness, but I found it a very unpleasant and terrifying condition. I must not, however, forget that it was at that bleak time that a very marvellous thing happened. Our youngest child Victoria was born.

Back at Westminster I resigned as PPS, but tried to get back into my parliamentary work. It was a depressing time. I was one of a bunch of backbenchers who had been enrolled to travel the country and explain the Industrial Relations Bill. This was a

measure

of inordinate length and complexity which sought in numerous clauses to distinguish between fair industrial practices which would attract legal immunities, and unfair practices which would not.

It is easy now with hindsight to see that this was entirely the wrong approach. There was no need to put the trade union

movement

into a legal straitjacket. All that was required was to remove their anachronistic privileges which was what eventually happened in the eighties. But at the time we could at least argue that, unlike the Labour government, we had not set out with the aim of fining strikers. This Bill, unlike the Labour one, was not about criminal penalties but civil remedies for those harmed by unfair action. What we wanted was to strengthen the arm of responsible trade unionists against the wildcats and set in place better procedures for dealing with disputes. And for all its complications, the Bill did give the trade unionist rights he had never had before such as longer periods of notice and compensation for unfair dismissal.

Clearly something had to be done to deal with growing

industrial

anarchy and the violence being used in pursuit of so-called

industrial disputes. During the 1972 building workers' strike, coaches were hired to transport so-called âflying pickets' to various building sites with the object of stopping work going on there. When some of the pickets eventually appeared to stand their trial at Shrewsbury Crown Court they were described as having swarmed onto a site âlike a frenzied horde of Apache Indians, chanting “Kill, kill, kill, capitalist bastards”; this is not a strike, it's a revolution.' The trial judge, Mr Justice Mais, described it as âa terrifying display of force, with violence to persons and property putting people working on the sites and local residents in fear'. I gave short shrift to a trades council delegation urging me to raise in Parliament the plight of the men who had been sentenced.

But when the Industrial Relations Bill became law it soon began to cause trouble. The National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC) issued warrants for the arrest of three dockers who it was alleged had wilfully disobeyed a court order to stop blacking a container depot in east London. A shutdown of the docks was threatened and the Official Solicitor went to the Court of Appeal and got the order set aside.

But what really caused morale on our side of the House to reach rock bottom was the government's decision to introduce a price and incomes policy, thereby contradicting almost everything said by the Party at the general election. And, of course, it was this policy which led eventually to the miners' strike and the

government's

downfall.

Along with all my colleagues I argued that we could not give in to the miners' claim. Firstly, we would be saying there was no future in moderation and that extremism paid. Secondly, we would have moved one stage nearer the catastrophic inflation Germany

experienced

in the 1920s. Soon people would be bringing their money home in wheelbarrows and the pound note worth little more than waste paper. Like my colleagues, I pointed out that many trade

union leaders had said that the communists were using the miners' dispute for political ends and suggested that Wilson knew this and should come out and say so. After all, he himself, when Prime Minister, had recognised that âa tightly knit group of politically motivated men' were behind the seamen's strike in 1966. He had also talked in those days of âone man's pay increase being another man's price increase'. But when I went off to do a live television debate in Rawtenstall with Eric Heffer and Cyril Smith, I was not very successful in selling these arguments and had a rough ride. I could, however, take some pleasure in the fact that I annoyed Eric Heffer so much that when the show was over but with the cameras still on us he took a swing at me. That is the sort of thing which makes good television.

Meanwhile Gilly was beavering away in the constituency. She was a Samaritan and had also launched a project to help the homeless. We were soon proud owners of a house in Padiham for battered wives which was almost always occupied by someone in urgent need. Once, in breach of all the rules, she went on her own to see one of her Samaritan customers. She was in such a hurry to get to his rescue that she left her car in the street unlocked and with its headlights on. The police came along and concluded that she had been kidnapped. They knocked on the door of a nearby house and were rather aggressive with the occupant who seemed to think they were accusing him of secreting the MP's wife on his premises. He protested that it was the last thing he would do. He was Len Dole, the Labour agent.

When the House of Commons met in January 1974 the whips were busy canvassing opinion as to whether we should go to the country on a âWho rules Britain â the miners or Parliament?' ticket. I felt then, and still feel, that we would have won if we had gone there and then, but while we stood ready for the off, no one fired the starting gun. Instead, the press was full of charge and

countercharge

as to what the offer for the miners meant and with rumours that the government and the National Coal Board were at

logger-heads

. By the time Parliament was dissolved the advantage had passed to the Opposition who used the simple slogan: âWe'll get Britain back to work'.

It was a difficult campaign in Nelson & Colne, but I was

reasonably

confident that I would squeeze home because of all the spade work we had put in over the years. I did â by 179 votes. In the country Labour failed to get an overall majority but won the largest number of seats and after Ted failed in his attempt to form a

coalition

with the Liberals, Wilson accepted the Queen's commission to form a government.

Sadly, my father-in-law Alan Green lost in Preston South and never got back in the House. It was the end of a very disappointing political career which started with such promise, but was a perfect example of how dedication and loyalty to a particular area can be a person's downfall.