David Jason: My Life (9 page)

Read David Jason: My Life Online

Authors: David Jason

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Television, #General

My fandom endured. In 1963, I went to the Duke of York’s Theatre to see Spike Milligan in

The Bedsitting Room

, the satirical play he wrote with John Antrobus. I had never seen anyone come out of character onstage and address the audience, as Milligan did that night. I was in the fourth row of the stalls and Milligan spotted a girl at the front, eating sweets. He broke

off to ask her what she was eating and whether he could have one – which she gladly gave him. He leaned forward over the footlights and took a sweet from the box she offered up to him. He bit into it and held it up to his ear, saying, in a squeaky voice that might well have been coming from the sweet, ‘Help! I’m a prisoner in a Malteser factory!’ It was the most avantgarde thing I had witnessed. Afterwards I went and hung around in a small knot of people at the back of the theatre, until Milligan came out and sat on the steps for a while, when I was able to get his autograph on a scrap of paper. That autograph meant a lot to me for years after.

Another seminal theatrical experience: in late 1958, my good friend Bob Bevil and I found ourselves putting in some sockets in a flat in Hyde Park Square Gardens and getting into conversation with the American guy who was renting it. And he said he was appearing in a show in the West End and asked us if we would like a couple of tickets. The show was

West Side Story

. It had opened on Broadway the previous year, and then transferred to London, with some of the original American cast. And, of course, it was stunning, especially for two working lads from north London – the songs, the choreography, the sets, the sheer punch of the orchestra coming out of the pit at you. It blew my mind away, and is still my favourite musical to this day.

And the bloke whose sockets we did? That was David Holliday, who starred as Tony. Holliday would go on to play many distinguished theatre roles, singing and non-singing, and (truly impressive, this) to be the voice of Virgil in the first series of

Thunderbirds

. But I’m sure he would concede that he would have been nothing without Bob’s and my sockets at that pivotal moment in his career.

Back at work, Bob and I found ourselves doing a rewiring job on a big house in Highgate that was being renovated. This substantial and well-appointed property, we came to realise, was

the home of Billy Wright, the footballer, and Joy Beverley, one of the Beverley Sisters singing group. They had married in 1958 and that union of ultra-famous England captain with ultra-famous pop singer made them the Posh and Becks of their day. Of course, I wasn’t expecting to meet either of the residents in the course of these labours, realising that both of them probably had better things to do than stand around watching an electrician run a length of copper wiring up the side of their yet-to-be-decorated sitting room.

But that only goes to show how wrong you can be, because one day, while I was up to my shins in wiring, in walked Joy Beverley. And not just Joy, either. She was accompanied by one of her sisters – either Teddie or Babs. I didn’t know which one it was. But that’s the tricky thing about identical twins, of course: what you’ve got to understand is, they look alike. It’s why we call them twins. Still, whether it was Teddie or Babs, or Babs or Teddie, just to be in the presence of these people – just to be said ‘hello’ to by them, as they crossed the room – was excitement beyond words. I think my eyes must have become dinner plates. I felt like I had come into contact with a world as far removed from mine as it was possible to imagine, a world of glamour and stardom and wealth.

Opposite the cul-de-sac that the house was situated in was a little park on the edge of a hill, with a bench in it, and come lunchtime, I sat there on my own with my chips, my milk and my bread and stared out across London.

* * *

I

N

1958 I was in trouble with the law again – this time for riding a motorbike without learner plates. Or, rather, as the summons put it, ‘without displaying in a conspicuous position on the front end or the rear of such vehicle the distinguishing mark’.

Stood to reason, though, didn’t it? If you hadn’t passed your

motorbike test, you weren’t allowed to carry anyone with you. Therefore, if you wanted (as I frequently did in those days) to sling your mate Micky Weedon or Brian Barneycoat on the back and zoom off to Southend for a day on the beach, there was nothing for it but to get rid of the L-plates.

Result: a steep, ten-shilling fine. But no ban, fortunately.

I had always planned to have a motorbike. Cars were an unattainable dream at this point – way out of our price range. It was the motorbike that was the working-class man’s vehicle of escape. And as soon as I had a little money coming in, I could make the motorbike plan a reality. But even then, for me, it remained a luxury item. When Ernie Pressland from next door was called up for national service, he flogged me his drop-handle push bike, and that’s what I continued to go to work on. The motorbike was for weekends and for pleasure.

In 1957, when I was seventeen, a cousin’s boyfriend had a friend whose friend’s friend was friendly with a friend who had a cousin whose boyfriend had a repair shop up at Muswell Hill, and he pointed me the way of a bloke who was selling a bike from his garage at home. It was a 350cc BSA B31 – a bit of a beast, in all honesty, and certainly a much more powerful machine than I was looking for. But the bloke selling it was very persuasive. He said, ‘You’ll only want a bigger one when you get used to it. You might as well start with a proper bike that’s going to really look after you.’

He had a point. Besides, the bike had taken on a romantic lustre in the half-light of the garage and I was already smitten. I parted with all the money that I had been stashing away in the Post Office and took him up on his generous (and quite cunning, as it would turn out) offer to ride the bike home for me.

Nobody taught you to ride a motorbike in those days. You gleaned what you could from people who already had bikes, and the rest you discovered for yourself by trial and error. And

if you happened to be a little short in the leg, your trials and errors were made no easier. You had to learn how to climb aboard, and how to throw your full eight stone down onto the kick-start. If it didn’t kick back, the bike started. If it started, you rocked it forward off its stand. If you could get it off its stand, you could start feeding the power in as you let the clutch out. And then you could stall it and start all over again. And once you’d mastered that end of the business, all that remained was to discover how to travel forwards on two wheels without falling off. (The almost total lack of traffic on the roads in those days definitely played into one’s hands here.)

All went swimmingly for a few days, my pride surging as I coolly piloted my new machine around the neighbourhood, fancying myself very much the liberated bachelor – until one morning, at the bottom of our road, a worrying noise started up, as if someone were clinging on to the bike’s underside and attacking the engine with a hammer.

I climbed off to have a look. The downtube that came from underneath the petrol tank and held the engine in beneath the crossbar had come apart and the engine was waving about like a flag in the wind. In a state of nearly tearful distress, I wheeled the crocked bike back home, and then returned to see its former owner for an explanation – or, better than that, the return of my hard-earned savings. He was, as you might guess, less than helpful. ‘Nothing to do with me, guv,’ he said. ‘Sold as seen, mate.’ And with that, the door closed.

I was mortified. All my savings! Gone! Evaporated! Stolen! After a few days of wandering around in despair, I lashed the engine on with wire and pushed the thing to a repair shop on the high street, where I was told that I’d been flogged a grade-A pup. The bike had been in an accident which had entirely broken its frame, and the owner had welded it back together and painted over it. It would take weeks to make the thing roadworthy again. Collapse of super-stud’s ego.

Still, that was my first motorbike – little beloved by my mum, who naturally feared, as mothers will, that I was destined to end up killing myself on it, and who also deeply resented my habit of stripping the engine down and performing running repairs in the kitchen. She certainly didn’t like the way I would boil up the chain in a lubricating solution of molybdenum disulphide in a saucepan on the stove, while de-coking the cylinder head on the dining table.

A year or so later, with some more hard-earned money salted away, I was able to trade up, chopping in my historically damaged B31 at Slocombe’s on the North Circular Road at Neasden. What I swapped it for was a long-coveted 495cc BSA Shooting Star – sometimes known as a Star Twin and the first BSA model to go into production after the war. That wonderful piece of machinery was to take me all over Britain – east to Clacton, west to Cornwall and north to the Lake District. I still have a copy of it which I have restored to look like the original – again, after salting away some hard-earned cash.

In the summer of 1960, I used that bike to head out to Essex. We North Met electrical apprentices were dispatched to a training centre at Harold Hill for a month-long course on metalwork and welding. I was put up in digs with a family nearby for five nights a week, and went in each day to the brazing shop, where I found myself in a class of lads from all over the south of England, all sent to learn metalwork and its associated arts, including one or two East Enders who looked like they would have your innards out with a welding iron, if you weren’t too careful. Still, we all seemed to rub along well enough. In fact, a camaraderie swiftly developed, with the trainees ranged against the instructors, who wore brown coats and were largely stern and humourless, patrolling the workshop and barking orders: ‘Stop talking! Back to your station!’

You were in a big hall, with two long rows of desks, lathes to one side and, behind glass screens, the brazing area, with its

forges and giant anvils. Everyone had his own station, where he had a vice, a metal block and a drawer full of tools. It was a scene ripe for undermining and for nefarious practices of all kinds, and my good friend Bob and I rather ended up running the place in this regard. We’d send the word around: ‘At eleven o’clock, two minutes of banging.’ Come the moment, the room would abruptly explode into a cacophony of ringing hammers, while the instructors buzzed around in confusion: ‘What’s going on? Stop this!’

We came to think of ourselves as prisoners of war, with the instructors as the prison guards. At lunchtime, we would solemnly form up in two lines, and, on the command from Bob and myself (‘Atten-shun! By the left …’), march across the tarmac to the canteen – or, as we preferred to think of it, the cookhouse – whistling ‘Colonel Bogey’, just as we had seen it done in the movies, although, in this case, watched by the girls from the secretarial course, who would come to the windows to see what the noise was about.

Incidentally, the canteen had two sets of doors, sandwiching a small box-like entry hall to keep out the draught, about six feet square and eight feet high. It was the tendency of our febrile minds to imagine that this area was an airlock, and that you could only open the inner doors when everybody was inside the foyer and the outer doors were closed. So, at the conclusion of our march from the brazing shop, and on the command ‘Fall out!’, we would open the outer doors and then squeeze into the hallway before advancing. How many apprentice electricians can you fit in the entrance to a technical college canteen? This was a question we answered most lunchtimes – the answer being, a lot more than you’d think, especially if you double up and hoist a few onto your shoulders.

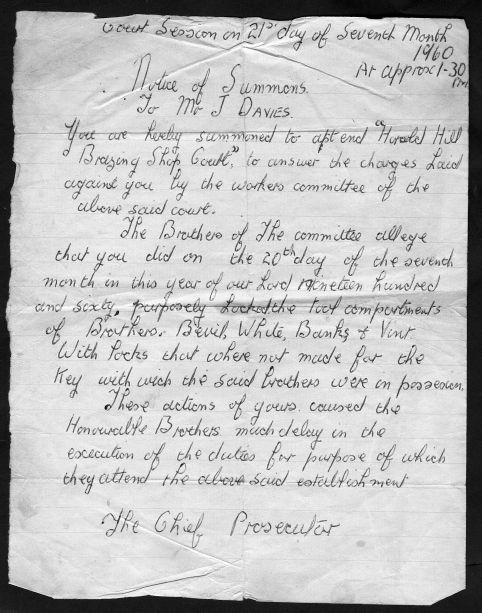

We eventually had a mock judicial system up and running, too. Offenders – those perceived to have acted in ways contrary to the ethos of the workshop – would receive a summons from

the Brazing Shop Court, and be required to attend a hearing at the appointed time during a given lunch hour. At first we hand-wrote the summons, but as the judicial system grew more sophisticated, we had them typewritten by a girl on the secretarial course in her spare time. (Think of it as our version of prisoners of war forging passports.) I still possess one of these documents, issued, it would appear, to a Mr J. Davies.

In court, we would hear from the prosecution and the defence, with me frequently playing the judge, deploying my metalwork hammer as a gavel, and handing down such sentences as ‘last in line for the canteen next Thursday’. This managed to keep us entertained until the course ended, although I should probably point out that we did find time in our busy day to learn a few things as well.

All in all, my life seemed to be coming together in this period – or, at any rate, settling into a rhythm. I was learning a steady trade. I had some steady money coming in. I had a steady hobby – the amateur theatre. I had a steady motorbike. I had even started seeing a girl quite steadily – Sylvia Cunningham, whom I had met at a party in 1959. During our apprenticeship with the Electricity Board, Bob and I had been doing some wiring in a flat opposite the swimming pool in Finchley. The daughter of the people who owned the flat was going to be engaged to a guy called Tony and was throwing an engagement party. She invited Bob and me along. There, I was smitten from across the room by the sight of a beautiful woman with jet-black hair and a figure to die for, whom I eventually managed to pluck up the courage to speak to, and whom, by the end of the evening, I was desperate to see again. It turned out that she lived with her parents, on the other side of London from north Finchley, in Lee Green, south of Blackheath – a fifteen-mile trip. But, of course, that was no barrier to an apprentice electrician with ardour in his heart and his own motorbike.