David Jason: My Life (10 page)

Read David Jason: My Life Online

Authors: David Jason

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Television, #General

And I must have been serious about Sylvia because I took her to the West End on occasion for a wide-screen Cinemascope film presentation – and not just that, but also a meal afterwards at the Golden Egg on Tottenham Court Road. The Golden Egg was a chain restaurant, and a rung or two down from the Angus Steakhouse, I will admit, but it still served notice of a man’s firm and reliable intent. As the name would tend to indicate, it allowed you to have any form of egg – egg and chips, double

egg and chips, omelette and chips, double egg omelette and chips, double egg omelette and no chips, and even egg with no chips. And it had window seats where you could sit and look out at the world going about its business, and the world could look in at you going about your business – eating egg and chips. In terms of high-living, this place clearly took the egg and chips.

Sylvia and I ended up going out for a number of months, and she was, it seemed to me, at the oh-so-experienced age of nineteen going on twenty, the love of my life. That said, in conversations with her during the course of our relationship, when I once or twice gently floated the notion of perhaps one day devoting my life to acting, it never went down particularly well. Sylvia made it abundantly clear that she didn’t want to end up with a thespian. She found it a very unsettling thought. She wanted, as she put it, a ‘steady’ man. And fair play: no actor, to my knowledge, has ever been described as ‘steady’ – at least, not in the opening sentence.

Sylvia had her own ideas about the future, and she often voiced them: a nice little house, two-up and two-down, with a Morris Mini Minor in the drive. That was the dream. She was quite specific about the Mini, which was brand new then, and all the rage. And, to a large extent, I could see the appeal of it all, and shared it. It was the comfortable, conventional place towards which our relationship was probably headed. The electrician and his wife, their house and their car and, no doubt, in due course, their kids.

And then, one night in July 1960, during the month I was staying in Harold Hill on the Electricity Board’s welding course, Sylvia invited me over to her place. Her parents were going to be out – off at the cinema. The house would be empty for a couple of hours – just the two of us. I can’t deny it: heading south by motorbike and anticipating this extremely rare evening of isolated togetherness, visions of intimacy danced in my head. Alas, though, those visions were not realised. The house was,

indeed, achingly void of all others for the evening. It was a bungalow as well, so we wouldn’t have had to go far to get to the bedroom. But the telly was on in the sitting room and we watched it in near silence, pausing only to sip tea. There was no intimacy, rare or otherwise, nor any mention of the possibility of intimacy. Not so much as a peck on the cheek, let alone a snog on the sofa. Sylvia, engrossed by the telly, sat in her father’s large and comfy chair while I was marooned in misery on the sofa. What seemed like an ocean separated us.

Time wore on. Her parents were due back. Disconsolately, I got up to leave and stood by the sitting-room door.

‘Well, I’d better be going. I’ve got a long ride ahead,’ I said.

A pause.

‘Goodbye, then,’ I said.

A pause.

‘Goodbye, then,’ said Sylvia, not moving from her chair. I don’t think she even moved her eyes from the television.

I went out into the hall and completed the fairly lengthy task of re-donning my motorcycle gear. No expensive leathers for me, alas, but, rather, some cheapskate protective kit of a plasticky rubber construction. These items weren’t the best for insulation either: in the winter, you had to stuff an extra layer of newspaper down your front to protect your stomach from icing over in the wind. The trousers ballooned, the shoulders were uncharismatically square. I looked like a miniature Darth Vader.

Thus rubberised, I reappeared in the door frame of the sitting room.

‘Aren’t you going to kiss me goodnight?’ I said, sounding somewhat plaintive.

There now ensued an odd kind of Mexican stand-off. Sylvia clearly felt that if I wanted a kiss I should go over to her chair to receive it. My feeling was that if Sylvia deigned to get up and cross the floor, it would at least partly make up for the

evening’s unexplained coldness, and its failure to serve up those visions of nirvana that had been with me on my long bike ride over.

A perhaps not especially adult impasse followed.

‘You come over here,’ said Sylvia.

‘No, you come over here,’ I replied.

‘No, you come over here.’

This was threatening to go on for quite some time.

‘I’ll meet you halfway,’ I said diplomatically.

‘OK,’ she said.

There were about six paces between us in total. I now took three of them.

‘So now you come your half,’ I said.

‘You’ve come halfway,’ she said, still not moving. ‘You might as well come the whole way now.’

‘No, you come halfway.’

‘No, you come the rest of the way.’

We’d probably still be there now if I hadn’t turned round, unkissed, and walked out.

I headed down the garden path to the little gate, as purposefully as a man can who’s wearing several pounds of cheap black rubber. There at the kerb stood my faithful steed, my BSA 495. I mounted up. By this point, Sylvia had come out of the house and down the path.

She said, ‘But what’s the matter? You didn’t even kiss me goodnight.’

I said, ‘You didn’t seem to want me to.’

And with that, I kicked the bike into life and drove away.

What a journey that was. Hell hath no fury like a man spurned and on a motorbike, and on the long ride back to my digs in Harold Hill, frustration and humiliation duly boiled up. Yet somehow, instead of yielding blind anger behind the handlebars, leading to a dangerous lack of lane discipline at roundabouts, it appeared to produce clarity and conviction and a whole new

self-certainty. Accordingly, I may be one of a very limited number of people to have experienced a Damascene conversion in the Blackwall Tunnel. At least, it’s that portion of the journey home that I particularly recall – things clicking into place, a firmness of purpose cohering in my mind despite the noise of the bike cannoning off the walls. I swear that in that unlovely, grubby and actually rather unsuitably narrow passage beneath the Thames, under the electric lights, the scales fell from my eyes.

By the time I got back, I was fully and absolutely resolved. Stuff it all. Stuff the steadiness. Stuff the two-up, two-down and the Mini on the drive. Stuff the conventional path I’d slowly been drifting up. That wasn’t my future. I was going to do the unsteady thing. I was going to become an actor. I didn’t know how, but there had to be a way, didn’t there? And even if it took me a while (which it would – several more years in fact), I was going to find it.

While on the course, I had been loyally phoning Sylvia from the phone box opposite my digs. Now I stopped. After a few more days, I returned to Finchley and I didn’t phone her from there, either. It was as abrupt as that. It alarms me now to think how easily my twenty-year-old self shut down on someone. But it was like a thrown switch. Some moments alter the course of the rest of your life, and that was one of them.

CHAPTER FOUR

The rejection of a promising career as a pirate. Some slightly questionable business involving bongos. And a change of name.

IN LATE 1959

the period of my apprenticeship with the Electricity Board came to a finish – and not, alas, a triumphant finish. The EB informed me that they were declining the opportunity to take me on into full-time employment. They declined the opportunity to take on Bob Bevil too, so at least I wasn’t the only one. Was that because the pair of us had spent such a large part of our apprenticeships mucking about, forcing ourselves into imaginary airlocks, staging mock trials, stapling people to the floor through their boiler suits, etc.? I wouldn’t care to speculate. All I know is, when our term had run its course, the Board somehow felt able to let us go.

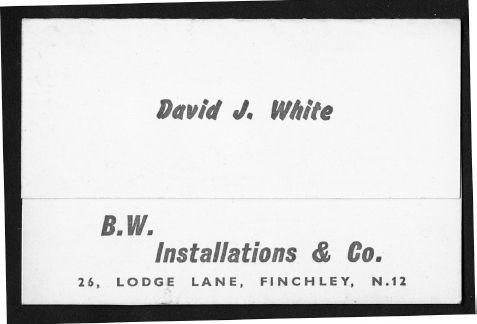

But I had at least got some training and a certificate under my belt. So, Bob Bevil and I decided to go into business together as electricians. We must have been serious because we had our own business card printed up – one with a fold in it, none of your cheap nonsense. On the top flap was my name – David J. White – and then the card opened up to reveal the legend ‘B. W. Installations & Co. – Electrical Contractors, Intercommunication

Engineers’, along with the address and telephone number of our head office: my parents’ house at Lodge Lane, Hillside 3526. (Finally, regular use was found, beyond Christmas and royal visitations, for that neglected front room, which became our headquarters.)

Intercommunication Engineers? Oh yes, most certainly. In the course of going about our business, Bob and I had met an Irish subcontractor who was installing door-answering equipment imported from Italy – the buzzer and two-way intercom system which is absolutely standard and unremarkable now but represented an exotic leap forward for technology in those days. ‘What? You mean I can lift this receiver and find out who’s at the door without coming down thirty-four flights of stairs? Why, it’s an electric-powered miracle.’ And loads of blocks of flats were going up in the holes left by the Luftwaffe, so this was something of a boom area at the time, meaning that our Irish contractor friend had lots of work to pass on to me and Bob – ripping us off royally in the process, we would eventually work out, but for the time being we

were absolutely delighted. B. W. Installations & Co. was up and running. Which wasn’t acting, of course. But it was a living.

Meanwhile, the acting was going well and my reputation in the small but slowly expanding corner of amateur dramatics that I occupied was continuing to grow. And my attitude towards it had decidedly changed. When I looked around at my fellow amateurs at the Incognitos, and in the various other am-dram companies that I was hooking up with in the early 1960s, I realised that there were distinct groups. There were some doing it because they loved it and because it was sociable. These were people who would probably have taken offence if you had asked them whether they had further aspirations in the theatre – like you had accused them of having some kind of ulterior motive, when, in fact, they were in it for pure fun and pleasure. I could sense that, although I had been a part of that group in the beginning, I no longer was.

Then there were others who wanted to be professional and were hoping for a break – that some day they would be discovered. It was only a matter of time. Someone from the West End or the movies would find their way up to Friern Barnet and be utterly staggered by what they saw from the old cinema seats. Then they would be waiting for you with a contract at the stage door, and the following day, or certainly within the week, they would make you a star. It seemed to me that, for quite a while, I had been quietly moving into that group. I had been one of those people who didn’t quite have the courage or the knowhow to take the future into their own hands, but who were waiting for it to happen – waiting to be discovered. And waiting to be discovered wasn’t necessarily going to work. You needed to find some way to make it happen, or you needed something, or someone, to give you a shove.

In my case, a big old push came in 1962. I was twenty-two and I represented the Muswell Hill Players at the Hornsey Drama Festival. I won Best Supporting Actor that weekend

– the first time I had ever won an individual award for my acting. I still have the trophy – a medallion of an angel waving some laurels around, attached to a simple wooden plaque, about four inches tall. The head judge at the festival was André van Gyseghem, a very distinguished man of the theatre who did lots of television work in the sixties. (Among many other things, he appeared in

The Saint

with Roger Moore and was Number Two in the great Patrick McGoohan series

The Prisoner

.) And in his commendation during the prizegiving, he stood up and told the room that, hesitant though he always was to encourage people to take up acting for a living, he would have absolutely no hesitation recommending me for a career as a professional. Such a public endorsement from such a qualified source really boosted my confidence.

Who would have thought that twenty-five years after André van Gyseghem gave me his blessing, I would know the glory of hearing my name called from the stage of the Grosvenor Hotel ballroom, of rising from my seat, dressed in black-tie finery, and of working my way through tables crammed with the great and good of British entertainment? And then of climbing the steps, with my legs almost giving way underneath me, to receive the 1987 BAFTA TV award for Best Actor, for my role as Scullion the Head Porter in the drama

Porterhouse Blue

?

Yet that simple small plaque, presented in those far humbler circumstances in Hornsey, will always mean … well, quite a lot less, actually, now I come to think of it.

But you’ve got to start somewhere – and to be honest, it was a good start. That prize in Hornsey was definitely another coin-drop moment.