Daughters of the Samurai: A Journey From East to West and Back

Read Daughters of the Samurai: A Journey From East to West and Back Online

Authors: Janice P. Nimura

Tags: #Asia, #History, #Japan, #Nonfiction, #Retail

DAUGHTERS

OF THE

SAMURAI

A JOURNEY FROM EAST

TO WEST AND BACK

JANICE P. NIMURA

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

FOR YOJI

CONTENTS

2.

THE WAR OF THE YEAR OF THE DRAGON

4.

“AN EXPEDITION OF PRACTICAL OBSERVERS”

14.

THE WOMEN’S HOME SCHOOL OF ENGLISH

Little Granddaughter, unless the red barbarians

and the children of the gods learn each other’s

hearts, the ships may sail and sail, but the two

lands will never be nearer.

—

ETSU INAGAKI SUGIMOTO

,

A Daughter of the Samurai

, 1926

Samurai training will prepare one for any future.

—

ETSU INAGAKI SUGIMOTO

,

A Daughter of the Samurai,

1926

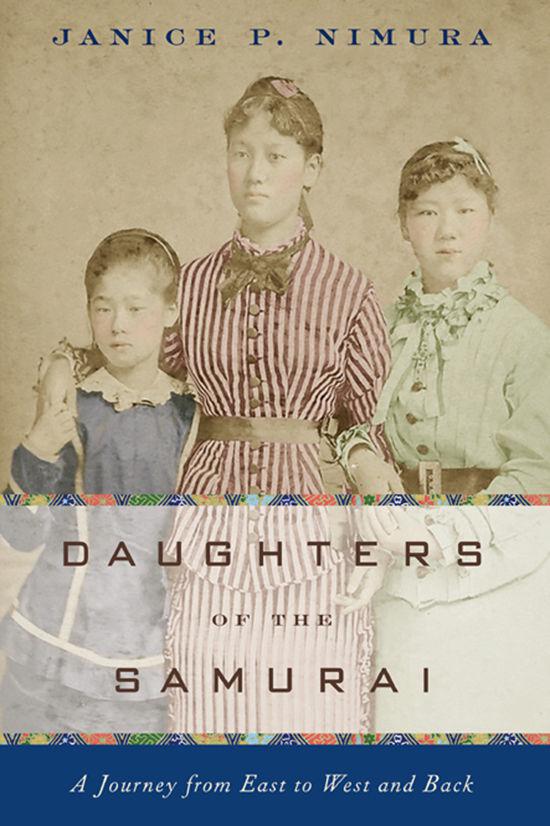

The girls on the occasion of their audience with the empress. From left to right: Tei Ueda, Shige Nagai, Sutematsu Yamakawa, Ume Tsuda, Ryo Yoshimasu

. (Courtesy Tsuda College Archives.)

NOVEMBER 9, 1871

I

N THE NARROW STREETS

surrounding the Imperial Palace, newfangled rickshaws clattered around corners, past the indigo hangings in the doorways of the merchants, past the glowing vermilion of a shrine’s

torii

archway, past the whitewashed walls of samurai compounds. The runners between the shafts gleamed with sweat and whooped at those in the way; the passengers, mostly men, sat impassively despite the jolting of the iron-rimmed wheels. Shops selling rice or straw sandals stood alongside others offering wristwatches and horn-rimmed spectacles. Soldiers loitered on corners, in motley uniforms of peaked caps and wooden clogs, short zouave jackets and broad silk

hakama

trousers. They stared at the occasional palanquin passing by on the shoulders of several bearers, wondering at the invisible occupant: an official, in a stiff-shouldered tunic? a retainer’s wife, on a rare outing to the local temple? Servant girls in blue cotton darted in and out of traffic, their sleeves tied back.

Tiny alongside the forbidding bulk of the palace’s massive stone embankments, five girls filed past. Two of them were teenagers; the others younger, the smallest no more than six. They were swathed in rich silk, the three older ones in paler shades embroidered all over with leaves and trailing grasses, cherry blossoms and peonies; the other two in darker robes emblazoned with crests. Each girl’s hair was piled high in heavy coils and loops secured with combs and pins. They held themselves carefully,

as if their elaborate coiffures might overbalance them. Their painted lips were crimson bows against the powder that whitened their cheeks. Only their eyes suggested anything other than perfect composure.

Imposing timbered gates rumbled open to admit them, and then rolled closed again. Inside, all was quiet. Within this maze of fortresses and pleasure gardens, time flowed more slowly: everything seemed choreographed, from the movements of the guards to the gentle fluttering of each flaming red maple leaf. The girls padded along corridor after twisting corridor, taking small pigeon-toed steps in their gorgeous new kimonos, the finest they had ever owned, each tightly tied with a broad stiff

obi

in a contrasting hue. Grand court ladies escorted them, hissing instructions: to keep their eyes on the polished floor just in front of their white split-toed socks, their hands glued flat to their thighs, thumbs tucked behind fingers. Floorboards creaked, silk rustled. The subtle perfume of incense wafted from behind sliding doors. Stolen glances revealed screens painted with cranes and turtles, pine and chrysanthemum; lintels carved with tigers and dragons, wisteria and waterfalls; flashes of vivid fabric, purple and gold.

At last they arrived in a cavernous inner chamber. A heavy bamboo screen hung there, though the girls dared not look up. Seated behind it, they knew, sat the Empress of Japan. The five girls knelt, placed their hands on the

tatami

-matted floor, and bowed until their foreheads touched their fingertips.

Had the screen been moved aside, and had the girls been brazen enough to lift their eyes, they would have beheld a diminutive woman of twenty-two. Her head was the only part of her that emerged from a cone of ceremonial robes: snow-white inner kimono, wide divided trousers of heavy scarlet silk, an outer coat of lavish brocade, edged in gold. Though she held a painted fan bound with long silken cords, her hands were invisible within her sleeves. Oiled hair framed her oval face in a stiff black halo, gathered behind into a tail trailing nearly to the floor, and tied at intervals with narrow strips of white paper. She had a strong chin, and prominent ears that lent her an almost elfin look. Her face was powdered white, her eyebrows shaved and replaced with smudges of charcoal high on her forehead. Her

teeth were blackened, in the style appropriate for a married woman, with iron filings dissolved in tea and sake, and mixed with powdered gallnuts. Though her husband had just been fitted for his first Western-style clothing, personal grooming for the women of the imperial court remained, for the moment, much as it had been for centuries.

Lacquered trays on low stands appeared before the girls, bearing bolts of red and white crêpe—auspicious colors—as well as tea and ceremonial cakes, also red and white. The girls bowed, and bowed again, and again, staring down at the woven tatami between their hands. They did not touch the refreshments. A lady-in-waiting emerged, holding a scroll before her. Her hands were graceful and astonishingly white as she unfurled it. In a high clear voice, using language so formal the girls could barely understand her, she read the words the empress had brushed with her own hand, words no empress had hitherto dreamed of composing.

“Considering that you are girls, your intention of studying abroad is to be commended,” she chanted. Girls, studying abroad—the very words were bizarre. No Japanese girl had ever studied abroad. Few Japanese girls had studied much at all.

The reedy voice continued. “When, in time, schools for girls are established, you shall be examples to your countrywomen, having finished your education.” The words were impossible. There was no such thing as a school for girls. And when they returned—if they returned—what kind of examples would they be?

The lady-in-waiting had nearly reached the end of the scroll. “Bear all this in mind,” she concluded, “and apply yourself to your studies day and night.” This, at least, the girls could do: discipline and obedience were things they understood. In any case, they had no choice. The emperor was the direct descendant of the gods, and these were the commands of his wife. As far as the girls knew, a goddess on earth—seeing but unseen, speaking with another’s voice—had given them their orders.

The audience was over. The girls withdrew from the scented stillness of the empress’s chamber and retraced their steps through the labyrinth of corridors to the clamor of the world outside the walls, no doubt light-headed

with relief. They returned to their lodgings laden with imperial gifts: a piece of the rich red silk for each, and beautifully wrapped parcels of the exquisite court cakes. So sacred were these sweets, it was said, that a single bite could cure any illness. The girls might be the newly anointed vanguard of enlightened womanhood, but their families were not about to trifle with divine favor. Portions of the cake were carefully conveyed to relatives and friends.