Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe (60 page)

Read Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe Online

Authors: Simon Winder

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Austria & Hungary, #Social History

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

‘The fat churchy one’

»

Night music

»

Transylvanian rocketry

»

Psychopathologies of everyday life

»

The end begins

‘The fat churchy one’

The Archduke Franz Ferdinand is one of the modern era’s terrible ghosts, doomed to re-enact year after year his floundering final hours, ostrich feathers everywhere, his body bulging in an absurd uniform. He is always en route to that wrong turn which will bring him face to face with the depressed young man, sitting in a Sarajevo cafe mulling over the pathetic failure of his assassination plot, who is suddenly presented with this incredible reprieve. Betrayed by his useless security arrangements and daft, pop-eyed, moustachioed appearance, Franz Ferdinand seems to cry out to be killed and usher in a new and awful world.

Franz Ferdinand spent almost his entire adult life rehearsing and war-gaming his upcoming role as Habsburg Emperor. From the age of twenty-six to his murder a quarter of a century later, he impatiently awaited his despised uncle Franz Joseph’s death. Of course we will never know if he would have been a ‘good’ Emperor. It may well be that he had just waited too long and that whatever qualities he might have possessed had long curdled, lost in a maze of ritual, uniforms, masses and – above all – hunting. His shooting skills made him legendary, belonging to that disgusting and depressing era when the aristocratic hunting expedition became married to modern military technology, unbalancing the entire relationship of hunter and hunted, so that shooting partridges became like a proto-version of playing

Space Invaders

. Franz Ferdinand totted up the dazing total of some three hundred thousand animals killed. The little woodland critters on his Bohemian estates must have indulged in a certain amount of high-fiving on receipt of the news from Sarajevo.

Franz Ferdinand’s reputation is doubly ruined – not just by the dumb, chaotic, portentous nature of his death, but by his comic role at the opening of Jaroslav Hašek’s

The Good Soldier Švejk

. The devastating opening chat between Švejk and his landlady – where Švejk assumes that the Ferdinand whose murder has been announced must either be a Ferdinand who works as a chemist’s messenger or a Ferdinand who is a local dog-shit collector (‘Neither of them is any loss’) – has for many thousands of readers buried the Archduke for ever. The last straw is the landlady’s crushing correction: ‘Oh no, sir, it’s His Imperial Highness … the fat churchy one.’

In the modern Czech Republic, Franz Ferdinand’s home at Konopiště is a hugely popular tourist site and is at the heart of the renewed cult of the Habsburgs as happy rulers of a better time. Having frittered much of my life wandering around Central European castles, I think I can say with some authority that this is the most interesting of them all. Despite damage and theft by the Nazis, the interior of Konopiště accurately reflects its appearance when Franz Ferdinand and his family left it for the last time, en route to Bosnia. It is comparable perhaps only to Freud’s house in London as a picture of the inside of a particular mind. It also brings to mind Bartók’s

Duke Bluebeard’s Castle

, with each door opening to reveal a fresh aspect of the heir’s psyche. Franz Ferdinand was a great mental and physical cataloguer – a man who felt that he could know everything by systematizing everything – and he used Konopiště as an extension of his own memory.

As he shot animals around the world (everything from rhinos to gemsbok to emus) Franz Ferdinand carefully wrote down each kill, leaving a complete and dismaying record. Hundreds of these animals were stuffed and mounted, leaving whole corridors of the castle bursting with antlers, tusks, beaks, snouts, glass eyes, feathers and bristles. Just a moment of inattention while wandering past these heads could result in being gouged by something or releasing a nauseating shower of sawdust and skin. Wherever Franz Ferdinand travelled he had photos taken, and corridors are filled with his global wanderings, across Egypt and Australia, Canada and the United States (where he had, to his bafflement, actually to hand in his gun before visiting Yellowstone National Park). He collected weapons, many superb pieces being from his cousin the Duke of Modena, who bequeathed him not only heaps of wheel-locks, silver-chased partisans and jousting armour, but also so much money that he became one of the richest men in Europe – independently of any Imperial money, much to Franz Joseph’s impotent fury. Entire rooms are stuffed with ingenious metal objects for killing people, in glass cases, in decorative patterns, hanging from the ceiling. Franz Ferdinand also collected statues of St George (although his favourite saint was St Hubert – patron saint of hunters) and every nook and niche is filled with beautiful, strange or indifferent sculptures of George, with or without dragon. In all this monstrous accumulation of

stuff

there is something eerie and excessive. There is even a wing of the castle built specially for his cousin and friend Crown Prince Rudolf’s use, filled with objects of a kind which the young Franz Ferdinand thought would please him. Rudolf killed himself without ever visiting the castle, but the wing, with its wood panelling and air of masculine, tweedy, outdoorsy common sense plus a slight whiff of eau de Cologne, was kept as a perverse shrine.

By the time that you have taken all this in – plus Franz Ferdinand’s obsessive diary of his geographical location for every day in his life (the page open, fascinatingly, on a visit to Waltham Abbey, the experimental explosive and gunnery laboratory outside London) plus his multi-compartmented leather travelling cases – it is clear that there was something very peculiar about the castle’s owner. Undoubtedly very clever, conscientious, focused, hungry for information, he was also humourless, narrow, grasping and an insatiable, unappeasable cataloguer of a chilling kind. Whether at Konopiště or at the Upper Belvedere Palace, his Vienna base, Franz Ferdinand spent year after year wondering how to reform the Empire and which Hungarians he would gaol first, poring over maps and books, cross-examining whole crowds of experts, all in preparation for when he would

at last

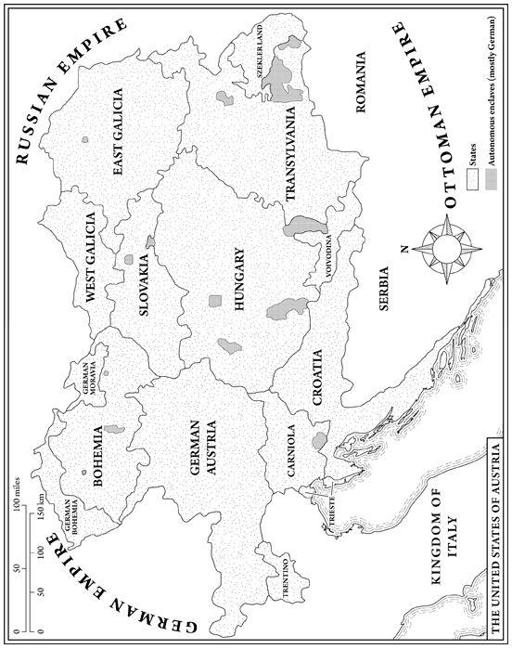

take over. He imagined for the Empire a definitive reorganization which would tidy it up, rationalize it and essentially bring it into line with his game diary, St George statues and serried flintlocks. We will never know if the plan for a United States of Greater Austria would have worked (there were many variants and it is unclear how seriously he took them) but on paper it seems tantalizing: fifteen ethnically coherent states with Vienna as the (very powerful) federal capital. To look at the map (designed by the Romanian Transylvanian Aurel Popovici) is to see a future which never happened – or only happened in part under the obscene, transient tutelage of the Nazis. The existence of such states as Szekler Land, Trentino and German Bohemia would have saved a lot of agony and the map has become an anguished commentary on what has happened in the century since it was proposed.

Franz Ferdinand was an unusual Habsburg in that he was poor at learning languages, and his complete failure to master Magyar may have been one of the reasons he hated Hungary so much. For his map to have worked the first obstacle had to be the destruction of the Hungarian state. The years of obfuscation, special pleading and hypocrisy by the Hungarian aristocracy so enraged Franz Ferdinand that he – a lifelong hater of democracy – became a warm supporter of a broad franchise just in Hungary (not in Austria) purely to enrage and then ruin the Hungarian aristocracy. He wanted to recreate the atmosphere of prostration that had prevailed back in 1849 so as to reshape the current botch and make a Habsburg super-state. These fascinating possibilities of course fall foul of the acute problems in achieving them. However friendless the Hungarians may have been, such a drastic reordering could have attracted malevolent Russian interest as well as Italian, Serbian and Romanian outrage of a kind that might well have led to some similar conflagration to that provoked by Franz Ferdinand’s murder. It also assumed that each nationality would have remained, once the Hungarians had somehow been disarmed, happy and merely

folklorique

within the bounds of Habsburg federalism. Why would the Bohemian Germans be willing to keep living in their little woodsy province rather than unite with the Second Reich? The plan (and Franz Ferdinand had many – so he may have spotted this flaw himself at some point) also failed to notice that it was the Hungarians who were the gendarmes, the most zealously brutal and anti-nationalist enforcers. Their neutralization would knock from the Habsburgs’ hands their most powerful weapon. In any event, some of the variants enshrined in Popovici’s map would ultimately be tried, with truly horrible results – but both the ruthless re-cutting of boundaries and the implicit violence had important origins in Franz Ferdinand’s mind.

In many of Franz Ferdinand’s political dealings there is the air of someone dreaming about how one day he will thrash all his servants in the hope that this will enforce obedience. But this was in many ways just his unpleasant personal manner and he was certainly no warmonger. One of the worst counterfactuals around his death is his role in the July Crisis, had he not caused it by being dead. He was no titan, but could he have shaped a more intelligent Austro-Hungarian strategy than the gang of fatalists and jittery oddballs who gathered around the ancient Franz Joseph? If much of the July Crisis was caused by the utter moral failure of Europe’s civilian leadership, then it is plausible to think that Franz Ferdinand’s enormous authority may have imposed a different pattern of thinking. He was always convinced that the motor for a stable and successful Europe was a German–Habsburg–Russian alliance, an alliance which had been, after all, highly successful for much of the nineteenth century. This perception that the three empires should support each other for dynastic, anti-democratic and anti-Polish reasons was very plausible – and indeed the perhaps needless alienation of Russia proved as great a disaster for Europe as the split between Britain and Germany.

These various combinations and options and possibilities ran back and forth in his mind as the years went by at Konopiště. But it was all against one very appealing piece of background. He may have been rude, narrow, sneering and an enemy to furry friends the world over, but he was a very good husband and father. With the usual historian’s despair at the wayward, unguessable nature of private life, it has to be said that Franz Ferdinand was unimpeachable here. Despite freezing disapproval from Franz Joseph, he insisted on marrying Sophie Chotek, a Bohemian aristocrat who was by Habsburg standards too common to be a suitable partner. They seem to have been devoted to each other and Sophie spent the rest of her life being snubbed and humiliated by the creepy court in Vienna, way down the list of precedence, sitting at some poky side table at banquets while her husband was up on the Emperor’s table. All this reinforced their decision to spend as much time as possible at Konopiště with their three children, Sophie, Maximilian and Ernst. A condition of the marriage happening at all was that any children could never succeed to the throne – a piece of vindictive madness but one that, as it turned out, at least saved the Empire from being ruled in the middle of the First World War by a fourteen-year-old Maximilian III.

The family provides the other really surprising and moving aspect of the castle. The nursery and the family rooms preserve a very privileged but nonetheless charming, modest and thoughtful existence, far removed from all the stuffiness and parade-ground shouting which made Franz Ferdinand so unloved in other contexts. The paintings and photos of the family, the toys, the drawings by the children take on a value which, while obviously sentimental, is nonetheless inescapable and upsetting – capped by a final photo of the entire family looking cheerful on holiday in Croatia just before Franz Ferdinand and Sophie headed off to Sarajevo, and then a final, final photo of the children posed in black and looking mournful in a staged and dated way after the news of their parents’ murder. The children were too obviously threats to the Anschluss and were lucky to survive. The sons were imprisoned by Hitler as soon as Austria was absorbed and two of the daughter’s children were killed fighting for the Third Reich.