Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe (38 page)

Read Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe Online

Authors: Simon Winder

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Austria & Hungary, #Social History

We do not know the details of the discussions that Joseph had with Catherine as they meandered down through the Crimea, but once the first partition had gone by without incident (and no European power had objected) there was little reason not to grab the rest. Both Catherine and Joseph could see the possibility of further happy pickings. The interesting question lay in whether or not they could successfully cooperate, or whether they might wind up as enemies. In the short to medium term both sides concluded that there was more than enough cake for everyone. Indeed as the French Revolution and its aftershocks came to dominate all other events, the rest of Poland disappeared almost unnoticed by the wider world, with two further partitions disposing of it – the second not involving the Habsburgs, but the third giving them a huge new area stretching almost to Warsaw.

The issue of the Ottoman Empire was what really enthralled Catherine and which now tempted her to dream of enormous projects. The highly satisfactory Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 had opened the way to her snatching the Crimea. She now explained to Joseph her new plans: to create a Kingdom of Dacia out of the eastern Balkans and a Byzantine kingdom at Constantinople, ruled by her grandson, helpfully called Constantine in anticipation. She and Potemkin had already celebrated the Greek heritage which Russia laid claim to by renaming the Crimean Khanate the Taurida Governate and founding or renaming towns with Greek names: Sebastopol (venerable city), Simferopol (useful city), Yevpatoria (a title of Mithradates VI) and so on. It was a mad project, but there seemed little to stop it and each new, enormous accretion of Russian territory made the next jump logical. Joseph returned to Vienna shaken and impressed, confronted by the issue which would dominate the Habsburgs’ nightmares until their own lands were in turn partitioned in 1918. He was of course well aware that Prussia had been out of control for decades, so this was a given and Frederick the Great’s further aggrandizement in Poland just depressing. But his truly horrible realization was that an independent Poland, however compromised, had been a valuable barrier of sorts and that inviting Russia so far west was a serious mistake. The Kingdom of Dacia did not sound appealing either as it would control the mouth of the Danube which, once cleared of its current unhelpful Ottoman owners, had the potential to become the Habsburgs’ key trade route. Were the Habsburgs in danger of being permanently boxed in by a monster?

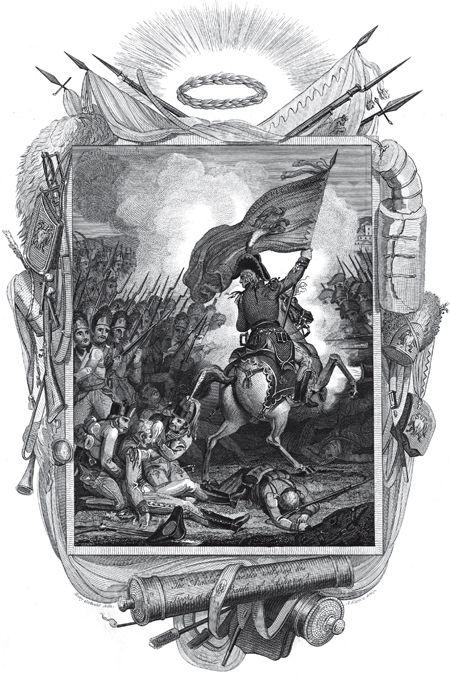

Bound by alliance with Russia, immediately Joseph reached home he was faced by a renewed Ottoman war. Constantinople had sensibly decided it should attack first rather than just wait for the Russians to chew it up again. Joseph marched into the Balkans at the head of an enormous army of some two hundred and fifty thousand men, full of chiliastic dreams about trumping Catherine’s vision. Unfortunately the army rapidly began to get ill and to starve – at least thirty thousand men died in the first year just of disease – and seemed set to achieve nothing. Joseph himself became very ill and returned to Vienna, where he died in 1790. He lived long enough to hear of a sensational series of Russian victories and then a Habsburg one, the successful storming of Belgrade. These events were marked by no fewer than five celebratory pieces by Mozart and then a

Te Deum

in St Stephen’s Cathedral, attended by a very unwell and chagrined Joseph, who had prepared all his life to lead his great, dynastic army to glory and found himself instead coughing in Vienna.

The Ottoman Empire was now finished as a serious menace to Austria and the principal shield-of-Europe purpose of the monarchy for some three hundred years came to an end. But, as usual, you have to be careful what you wish for and the Habsburgs now owned simply a new, impoverished, hard-to-defend block of Balkan land. This bound them, just as carved-up Poland did, to Russian goodwill at the same time as they were desperate to keep Russia away from the Danube. The collapse of the Ottomans also had curious implications for the Holy Roman Empire. The Habsburgs’ call on the resources of Germany had been as Christendom’s front line and countless Germans had fought on the eastern frontier. There were many reasons for the Holy Roman Empire to collapse in the decade after the old frontier shut down, but it is nonetheless curious that it should have been so soon. A similar dynamic can be seen in 1914, with the last Ottoman troops leaving most of the southern Balkans only a year before the beginning of the First World War. It is as though Constantinople provided a sort of discipline to Central Europe which, once removed, resulted not in the fruits of peace but in imbecilic mayhem.

Joseph, as he lay dying, was horrified to hear that his younger sister Maria Antonia (Marie Antoinette) was now under house arrest in Paris – but the responsibility for dealing with this would lie with his descendants.

CHAPTER NINE

‘Sunrise’

»

An interlude of rational thoughtfulness

»

Defeat by Napoleon, part one

»

Defeat by Napoleon, part two

»

Things somehow get even worse

»

An intimate family wedding

»

Back to nature

‘Sunrise’

Joseph II spent his reign at the heart of a gimcrack, exhausting machine of his own invention, which required him to pull all the levers and crank all the handles. It was as though he was personally atoning for all his predecessors’ blank-faced lack of interest in administrative reform. The effort killed him and there is something a bit mad and depressing about the whole performance. His view of himself as ‘first commoner’, albeit a first commoner who had to be unquestioningly obeyed in all things, led to any number of humiliations. Most enjoyable perhaps was his insistence on dressing in simple military uniform, which once resulted when he was walking outside St Stephen’s Cathedral in a priest sidling up to sell him pornographic pictures – which put the priest pretty much at the eye of the storm of all Joseph’s hang-ups.

But setting aside all the hectoring and oddness these inconsistencies had some happy results. Joseph’s enthusiasm for promoting new German opera resulted in Mozart’s

The Escape from the Seraglio

, the opera’s jokey Turkism itself an indicator of the Ottomans’ declining threat status. Then a further change of mind resulted in a more traditional switch back to Italian and Joseph’s personal authorization for

The Marriage of Figaro

, a story whose subversiveness is now almost invisible but at the time seemed a swingeing attack on the aristocracy, and therefore in line with Joseph’s own loopy antagonisms. The opera’s commission could not have been more traditionally Habsburg – a couple of bright outsiders of a kind who would have been familiar to Rudolph II, the Venetian Lorenzo da Ponte and the Salzburger Mozart. This wonderful magic box remains Joseph’s great gift to the world – a softened adaptation of a scathing French play that had notionally been set in Spain (i.e., ‘not France’), and turned into an Italian opera still set in Spain (i.e., ‘not the Habsburg monarchy’), but which in performance is almost always relocated to a patently Viennese milieu. Joseph’s world of short wigs and buckled shoes, all that quite dashing pre-Revolution flummery, is permanently preserved through the accident of its being hitched to a stream of the most beautiful, various and heartbreaking music and singing ever conjured up.

Vienna’s ability to attract a disproportionately large percentage of great composers, meaning perhaps ten people in a couple of centuries, is striking. Certain cultures at particular times provide the right facilities – the connoisseurship, the range of players, singers, copyists, venues, instrument-makers and, of course, audiences. Much of this is very alien to us. Our far, far broader access to such music makes us oblivious to how different the circumstances were under which it first appeared. In many cases it was exclusively for aristocratic audiences, or often for almost no audience at all, with a string quartet perhaps produced simply for one patron’s personal needs, or a piece designed for a specific player to unfurl in front of some tiny group.

This can be seen most clearly in the career of Joseph Haydn, much of which was spent tucked away in the private employment of the mighty Esterházy family on their estates south-east of Vienna. Here Haydn churned out a simply baffling, almost frightening, amount of music to order. A friend once gave me a boxed set of every one of Haydn’s symphonies and even these are unmanageable – like a nightmare where you are trying to cram into your mouth a sandwich the size of a dinner table. I have now spent years trying to take these pieces in, some four hundred movements of music, and it cannot be done. People have done their best to help – they have numbered and ordered them and some have jaunty nicknames (‘the Clock’, ‘the Hen’, ‘Hornsignal’, ‘la Chasse’), but the sheer scale defeats even these well-meaning efforts. Some of the symphonies are in practice quite boring and reek of loveless background music for the aristocratic soirées of yesteryear, with brocaded people who have not washed for quite a while kissing hands, fluttering fans and peering through quizzing-glasses. You can hit a really rough patch where you suddenly feel you have overdosed on lavender-flavoured comfits. But it is always worth persevering as something will turn up – a trio that sounds like an overheard, melancholy field-song (67th), a grand blaze of sound which is just right (75th), a strange droning that sounds like Sibelius (88th). It just goes on and on – there’s a bit that sounds like the opening of

The Valkyries

, another like nineteenth-century French salon music – but a lot of it, fair enough, sounds like Haydn.

This sheer productivity swamps everything – spectacular piano trios, a great sequence of string quartets, a hundred and seventy-five works for baryton (a defunct kind of bass viol favoured in Esterházy circles), operas, masses, a whole pile of concertos, piano sonatas, scores to accompany a marionette theatre – it is the high road to madness to try to encompass all this stuff. I love his music, but it is a bit disconcerting to realize that you could

die in extreme old age

and still only be familiar with a mere handful of the baryton trios. In that sense his own oeuvre becomes a deeply considered meditation on human frailty, even beyond his own Catholic devotion.

He lived so long that he tipped over into a Napoleonic world very remote from his roots in traditional Austria, one in which he became extremely famous and rich. But this came from the mere chance of living so long. One oddity is his extraordinary work

The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross

, written for orchestra but with versions for string quartet, oratorio and a stark piano transcription. In a sort of welter of traditional devotional feeling of a kind Joseph II would have bristled at, Haydn tried to dramatize in music each of Jesus’s final exclamations (‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do’ and so on), a commission for the highly severe Good Friday ceremonies in Cadíz cathedral. It is austere to the point of comedy, and is perhaps the last link in those near private sacred works like Biber’s

Rosary Sonatas

which had been used to channel the meditations of the Bishop of Salzburg over a century before. One of Beethoven’s teachers summed up a new scepticism by daring to suggest that Haydn’s setting of the words ‘I thirst’ in practice did very little to convey Jesus’s need for a drink. But then, there always seems to be a comment one can point to which appears to mark the end of traditional Habsburg Catholic devotion – and along comes Bruckner, or Webern.

Without doubt something is waved goodbye to in Haydn’s time, with his comparative isolation preserving forms of baroque piety hammered elsewhere by Joseph II. A perfect place to observe this is in Eisenstadt, where Haydn spent so many years of his life. This is a very sleepy town, part of an old, now drained swampland focused on the sprawling, surreally unpleasant Neusiedler Lake at the linguistic frontier where Germans and Hungarians bump into each other (as perfectly expressed by Franz Liszt/Liszt Ferenc being born down the road). A highly contested part of the world, as can be imagined, everything just peters out – into the forests, into the scuzzy lake, into bleak and tiny villages, an effect much exacerbated by the old line of the Cold War Anti-Fascist Protection Barrier. It will take many more years before the normal circulation of people can be re-established, or perhaps the enforced doziness will become permanent.

Eisenstadt is the home of the ‘Mountain Church’ where Haydn was finally buried. The church is a classic of severe Jesuit teaching, featuring a ‘holy staircase’ whereby the devotee clambers ever upward through heaps of tufa, past statue groups dramatizing the principal acts of the Passion. First put together in 1701, these have been much patched and repainted and gone through periods of being so unfashionable that they then required serious repairs. The tableaux seem as distant from any realistic form of worship as can be imagined, and yet they clearly fill the same religious world as

The Seven Last Words of Christ on the Cross

. For me the highlight was the scene of Jesus’s clothes being split up among the soldiers, a scene much enlivened by the spiders’ webs which filled the soldiers’ fingers.