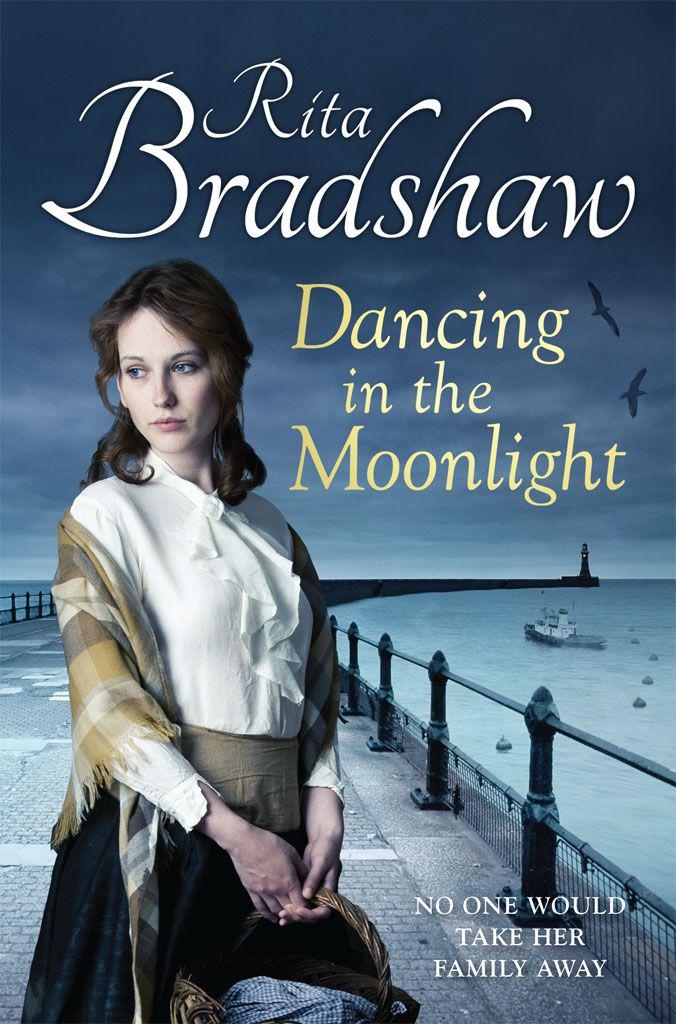

Dancing in the Moonlight

Read Dancing in the Moonlight Online

Authors: Rita Bradshaw

For my family.

Infinitely precious . . .

PART TWO

Along Came a Spider, 1928

PART THREE

Rising from the Ashes, 1928

PART FOUR

The Fishmonger’s Wife, 1929

PART FIVE

We Shall Fight Them on the Beaches, 1939

PART SIX

Greater Love Hath No Man . . ., June 1940

PART ONE

1925

Chapter One

She wasn’t ready to die. It was too soon. Death should come when you were resigned to it, when the pull of earthly ties had loosened their hold on the heart. That was the

right order of things, the natural progression, but she grew weaker every day. Sometimes she’d swear the Grim Reaper himself was at her elbow.

Raising herself a little in the narrow iron bed in which she was lying, Agnes Fallow waited a moment for the dizziness in her head that the movement had caused to subside before she said,

‘Put the kettle on, lass, and we’ll have a cup of tea before they’re back from school, shall we?’

Her daughter, who had just finished skimming the layer of froth from a scrag of mutton before adding the rice and mixed vegetables and putting the pan on the hob again, turned and smiled at her.

‘All right, Mam.’

It was a beautiful smile.

Lucy

was beautiful. Agnes sank back against the lumpy flock-filled pillows, closing her tired eyes. Every day she thanked God for her Lucy. It wasn’t

just that her oldest daughter was the only one of her brood to take after her, with her mass of golden-brown curls and deep-blue eyes, but Lucy was as kind as she was bonny. Look how the bairn had

taken herself off across the bridge into Bishopwearmouth and bought that roll of material from the Old Market a couple of months ago. She’d got the lads to fix it up as a curtain, which could

be pulled across the corner of the kitchen to hide her bed when she needed to use the chamber pot. None of the others had thought of that when she’d finally been unable to get outside to the

privy, only her Lucy.

Once the tea was mashed Lucy brought a cup to her mother, but seeing that she appeared to have fallen asleep, she stood looking down at her.

Her mam was thinner; her body barely made a mound under the blankets. As always when the fear came, Lucy told herself her mother would turn the corner soon. That’s what Dr Pearson had said

the last time he’d called, and he should know. Rousing herself, she bent and gently touched her mother’s shoulder, saying softly, ‘Have a sup tea, Mam. It’ll do you

good.’

‘What?’ Agnes’s eyes opened and stared for a moment before she blinked. ‘Oh aye. I must have dozed off for a minute.’

Without being asked, Lucy helped her mother sit up and positioned the pillow behind her. The worn winceyette nightdress did little to conceal the way Agnes’s bones protruded against the

skin covering them, the emaciated frame so frail that sick dread rose again. ‘Can you eat something, Mam? A biscuit to dip in your tea?’

Agnes shook her head, the hair that had once been as rich and shiny as Lucy’s now wispy and brittle. Pulling tighter the shawl Lucy had placed round her shoulders, she took the cup her

daughter was proffering and shakily raised it to her blue-tinged lips. It felt too heavy to hold.

‘I’ve put a spoonful of sugar in it. Sugar’s good for you.’ Lucy sat down on the edge of the bed with her own tea. Moments like this with her mam were rare and to be

treasured. From six o’clock in the morning, when she dragged herself out of the bed she shared with her sisters – eight-year-old Ruby and the twins, Flora and Bess, who’d just

turned two – she toiled without ceasing. After feeling her way downstairs in the dark she would light the oil lamp on the kitchen table and then persuade the fire in the range into a blaze,

before setting the big pan of porridge, which she had left soaking overnight ready for breakfast, on the hob. It was always nice and warm in the kitchen, unlike the bedrooms, which were icy. After

boiling the water in the heavy black kettle, she helped her mother wash her face and hands and tidy her hair. Then she made the first pot of tea of the day. Once it was mashed, she gave her mother

a cup and took one through to her father, who slept in the big brass bed in the front room, which he’d shared with her mother until she had been taken sick eighteen months ago. Something to

do with her heart, the doctor said. It had been then that they’d bought the narrow iron bed for the kitchen, where – in her mam’s own words – her mother could keep an eye on

things till she felt better. But she never had felt better.

By the time her two older brothers, Ernie, who was eighteen, and Donald, two years younger, came downstairs and joined their father at the kitchen table, their breakfast was ready and their bait

tins full. The menfolk left for Thompson’s shipyard at the end of the street as the buzzer started blowing at seven-thirty and were always through the gates before it stopped. It was

something her father and the lads prided themselves on.

Then she would rouse five-year-old John from the bed he shared with his brothers and chivvy Ruby into helping her dress the twins. They wriggled like eels and more often than not earned

themselves a slap or two from the impatient Ruby. Another round of breakfasts, followed by John and Ruby being packed off to school, and the day proper began; days of washing, ironing, cooking and

cleaning like the ones before them, winter and summer the same.

And she didn’t mind that, or the fact she often fell into bed too tired to undress, and had virtually had no schooling since her mam was took bad – she didn’t mind any of it as

long as her mam got well. On impulse, Lucy reached out her hand and touched her mother’s, an unusual show of affection in a family that was not demonstrative.

Agnes smiled. For a moment the warmth in Lucy’s deep-blue eyes banished the gnawing anxiety about how her family would cope once she was gone. If only there’d been grandparents or an

aunt or uncle to lend a hand, but she and Walter had both been orphaned as babies. He’d been brought up in a workhouse Gateshead way, and she in the one near Bishopwearmouth Cemetery. It had

been one of the things that had drawn them together when they’d met twenty-odd years ago one hot Sunday afternoon whilst taking a stroll in Mowbray Park, she with a girl friend and Walter

with a group of lads he worked with. Sweet sixteen, she’d been.

Agnes turned her head and looked to the window as the bitter northeast wind drove icy chips of sleet rattling against the glass. It seemed so long ago now, another lifetime, but she had been

bonny then and Walter had loved her. He still did love her, but a baby every year, only seven of whom had survived past their first birthday, had taken her looks and her health. She’d be

thirty-seven years old in a few weeks, but she knew she looked double that. And now here was her beautiful Lucy already doing the work of a lass twice her age. She hadn’t wanted that for her

bairn, to bear the responsibility of caring for the family when she was nowt but a child herself. And Ruby was no help. Little madam half the time, Ruby was.

Agnes sighed, her eyes closing. The familiar lethargy was taking over. Even the effort of drinking the tea was too much for her worn-out body.

Thank the good Lord they had neighbours like the Crawfords, she thought drowsily. Aaron and Enid Crawford had moved next door into one of the two-up, two-down houses in Zetland Street a week

after she and Walter had tied the knot. She and Enid had hit it off right away, and when Enid’s Tom had been born seven months later, she’d stood by Enid and told any nosy parkers the

baby had come early, although she’d known the truth. But it was funny, and whether it was the sins of the parents coming out in the children she didn’t know, but she’d never been

able to take to Tom Crawford. Enid’s three other lads were nice enough, but her eldest had been different from the day he was born. Even as a little lad he’d had something about him

which had made her flesh creep. She’d tried to discuss it once with Walter, but he’d looked at her as though she was barmy and she’d never mentioned it again. But she’d

thought all the more. And now Tom was a man, a big, good-looking man, and he liked her Lucy. There’d been a day in the summer when the lass had been sitting on the back doorstep in the sun

shelling peas, and Tom had stopped and talked to her over the wall. She had seen the look on his face, and her just a little bairn. But Lucy was growing up fast. Any day now she could start her

monthlies.

A sense of urgency piercing the blanketing tiredness, Agnes sat up straighter. It was time to have the little chat she’d been putting off. She would have liked to have done it more

gradually, a word here and there as the lass grew older, and then when Lucy got a steady lad she’d have given her an idea of what to expect on her wedding night, but she didn’t have the

luxury of time. She cleared her throat. ‘Lucy, lass, I need to talk to you about – about the birds and the bees. You’re a big girl now and – and soon things will change. Do

you understand what I’m saying, hinny?’

Her daughter’s blank stare was her answer.

There followed an exchange which was uncomfortable for both, but by the time the twins came hotching down the stairs on their bottoms, having woken from their afternoon nap, Lucy was better

informed. And more than a little horrified at what went on after marriage. She’d known men and women were built differently of course, and she had changed John’s nappy often enough

before he went into short pants to have become acquainted with male genitalia, but on the occasions when her da and the lads had their weekly bath in front of the range after bringing the old tin

bath in from the scullery, she and her sisters were not allowed in the kitchen. She still didn’t quite understand how a lad’s willy went into a lass – her mam had said that

happened naturally after marriage when a lass’s body became ready for it – but as it was the means of producing bairns, that must mean everyone did it. Even her own mam and da. And this

monthly thing that was going to happen to her body, when she couldn’t bathe or wash her hair in case she got a chill, sounded horrible. Following her mother’s instructions she’d

gone into the front room and delved into the trunk at the foot of the bed and found the wads of material that she had to pin into her drawers and wash through each day, but she’d felt like

crying when she’d looked at them. Once it began, it would go on and on until she was old . . .

After changing the twins’ damp nappies and settling the little girls on the clippy mat in front of the range with their pap bottles and a couple of the oatmeal biscuits she’d made

that morning, she started on the stack of ironing. Her mother was sleeping again, but this wasn’t out of the ordinary; she slept most of the time, and Dr Pearson said sleep was the best

medicine. And gradually the everyday routine settled Lucy’s agitation. The kitchen was cosy and warm and outside the sleet had turned to snow, a deep November twilight enhancing the glow from

the range and bringing a charm to the battered kitchen table and chairs and her father’s torn old leather armchair that they could never aspire to in the harsh light of day.