Dancing in the Glory of Monsters (2 page)

Read Dancing in the Glory of Monsters Online

Authors: Jason Stearns

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #War, #History

Introduction

Understanding the Violence

Power is Eaten Whole.

—CONGOLESE SAYING

This is how it usually worked: I would call up one of the people whose names I had written down in my notebook, and I’d tell him I was writing a book on the war in the Congo and that I wanted to hear his story. Most people like to talk about their lives, and almost everybody—Congolese ministers, army commanders, former child soldiers, diplomats—accepted. We would typically meet in a public place, as they wouldn’t feel comfortable talking about sensitive matters in their offices or homes, and they would size me up: a thirty-year-old white American. Many asked me, “Why are you writing this book?” When I told them that I wanted to understand the roots of the violence that has engulfed the country since 1996, they often replied with a question, “Who are you to understand what I am telling you?”

The look of bemusement would frequently appear in the eyes of interviewees. An army commander spent most of our meeting asking me what

I

thought of the Congo, trying to pry my prejudices out of me before he told me his story. “Everybody has an agenda,” he told me. “What’s yours?” A local, illiterate warlord with an amulet of cowries, colonial-era coins, and monkey skulls around his neck shook his head at me when I took his picture, telling me to erase it: “You’re going to take my picture to Europe and show it to other white people. What do they know about my life?” He was afraid, he told me, that they would laugh at him, think he was a

macaque

, some forest monkey.

He had good reason to be skeptical. There is a long history of taking pictures and stories from Central Africa out of context. In 1904, an American missionary brought Ota Benga, a pygmy from the central Congo, to the United States. He was placed in the monkey house at the Bronx Zoo in New York City, where his filed teeth, disproportionate limbs and tricks helped attract 40,000 visitors a day. He was exhibited alongside an orangutan, with whom he performed tricks, in order to emphasize Africans’ similarities with apes. An editorial in the

New York Times

, rejecting calls for his release, remarked that “pygmies are very low in the human scale.... The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date.”

While not as shockingly racist, news reports from the Congo still usually reduce the conflict to a simplistic drama. An array of caricatures is often presented: the corrupt, brutal African warlord with his savage soldiers, raping and looting the country. Pictures of child soldiers high on amphetamines and marijuana—sometimes from Liberia and Sierra Leone, a thousand miles from the Congo. Poor, black victims: children with shiny snot dried on their faces, flies buzzing around them, often in camps for refugees or internally displaced. Between these images of killers and victims, there is little room to challenge the clichés, let alone try to offer a rational explanation for a truly chaotic conflict.

The Congo wars are not stories that can be explained through such stereotypes. They are the product of a deep history, often unknown to outside observers. The principal actors are far from just savages, mindlessly killing and being killed, but thinking, breathing Homo sapiens, whose actions, however abhorrent, are underpinned by political rationales and motives.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a vast country, the size of western Europe and home to sixty million people. For decades it was known for its rich geology, which includes large reserves of cobalt, copper, and diamonds, and for the extravagance of its dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, but not for violence or depravity.

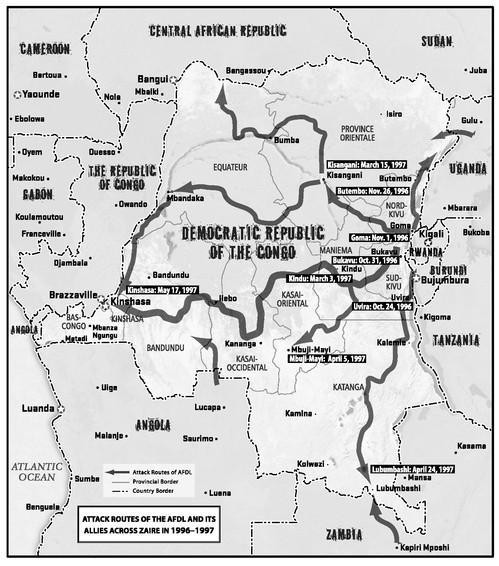

Then, in 1996, a conflict began that has thus far cost the lives of over five million people.

The Congolese war must be put among the other great human cataclysms of our time: the World Wars, the Great Leap Forward in China, the Rwandan and Cambodian genocides. And yet, despite its epic proportions, the war has received little sustained attention from the rest of the world. The mortality figures are so immense that they become absurd, almost meaningless. From the outside, the war seems to possess no overarching narrative or ideology to explain it, no easy tribal conflict or socialist revolution to use as a peg in a news piece. In Cambodia, there was the despotic Khmer Rouge; in Rwanda one could cast the genocidal Hutu militias as the villains. In the Congo these roles are more difficult to fill. There is no Hitler, Mussolini, or Stalin. Instead it is a war of the ordinary person, with many combatants unknown and unnamed, who fight for complex reasons that are difficult to distill in a few sentences—much to the frustration of the international media. How do you cover a war that involves at least twenty different rebel groups and the armies of nine countries, yet does not seem to have a clear cause or objective? How do you put a human face on a figure like “four million” when most of the casualties perish unsensationally, as a result of disease, far away from television cameras?

The conflict is a conceptual mess that eludes simple definition, with many interlocking narrative strands. The

New York Times

, one of the few American newspapers with extensive foreign coverage, gave Darfur nearly four times the coverage it gave the Congo in 2006, when Congolese were dying of war-related causes at nearly ten times the rate of those in Darfur.

1

Even Nicholas Kristof, the

Times

columnist who has campaigned vigorously for humanitarian crises around the world, initially used the confusion of the Congo as a justification for reporting on it less—it is less evil because it is less ideologically defined. He writes:

Darfur is a case of genocide, while Congo is a tragedy of war and poverty.... Militias slaughter each other, but it’s not about an ethnic group in the government using its military force to kill other groups. And that is what Darfur has been about: An Arab government in Khartoum arming Arab militias to kill members of black African tribes. We all have within us a moral compass, and that is moved partly by the level of human suffering. I grant that the suffering is greater in Congo. But our compass is also moved by human evil, and that is greater in Darfur. There’s no greater crime than genocide, and that is Sudan’s specialty.

2

What is the evil in the Congo? How can we explain the millions of deaths?

In 1961, the philosopher Hannah Arendt traveled to Jerusalem to witness the trial of a great Nazi war criminal, Adolph Eichmann, who had been in charge of sending hundreds of thousands of Jews to their deaths. Herself a Jewish escapee from the Holocaust, Arendt was above all interested in the nature of evil. For her, the mass killing of Jews had been possible through a massive bureaucracy that dehumanized the victims and dispersed responsibility through the administrative apparatus. Eichmann was not a psychopath but a conformist. “I was just doing my job,” he told the court in Jerusalem. This, Arendt argued, was the banality of evil.

This book takes Arendt’s insight as its starting point. The Congo obviously does not have the anonymous bureaucracy that the Third Reich did. Most of the killing and rape have been carried out at short range, often with hatchets, knives, and machetes. It is difficult not to attribute personal responsibility to the killers and leaders of the wars.

It is not, however, helpful to personalize the evil and suggest that somehow those involved in the war harbored a superhuman capacity for evil. It is more useful to ask what political system produced this kind of violence. This book tries to see the conflict through the eyes of its protagonists and understand why war made more sense than peace, why the regional political elites seem to be so rich in opportunism and so lacking in virtue.

The answers to these questions lie deeply embedded in the region’s history. But instead of being a story of a brutal bureaucratic machine, the Congo is a story of the opposite: a country in which the state has been eroded over centuries and where once the fighting began, each community seemed to have its own militia, fighting brutal insurgencies and counterinsurgencies with each other. It was more like seventeenth-century Europe and the Thirty Years’ War than Nazi Germany.