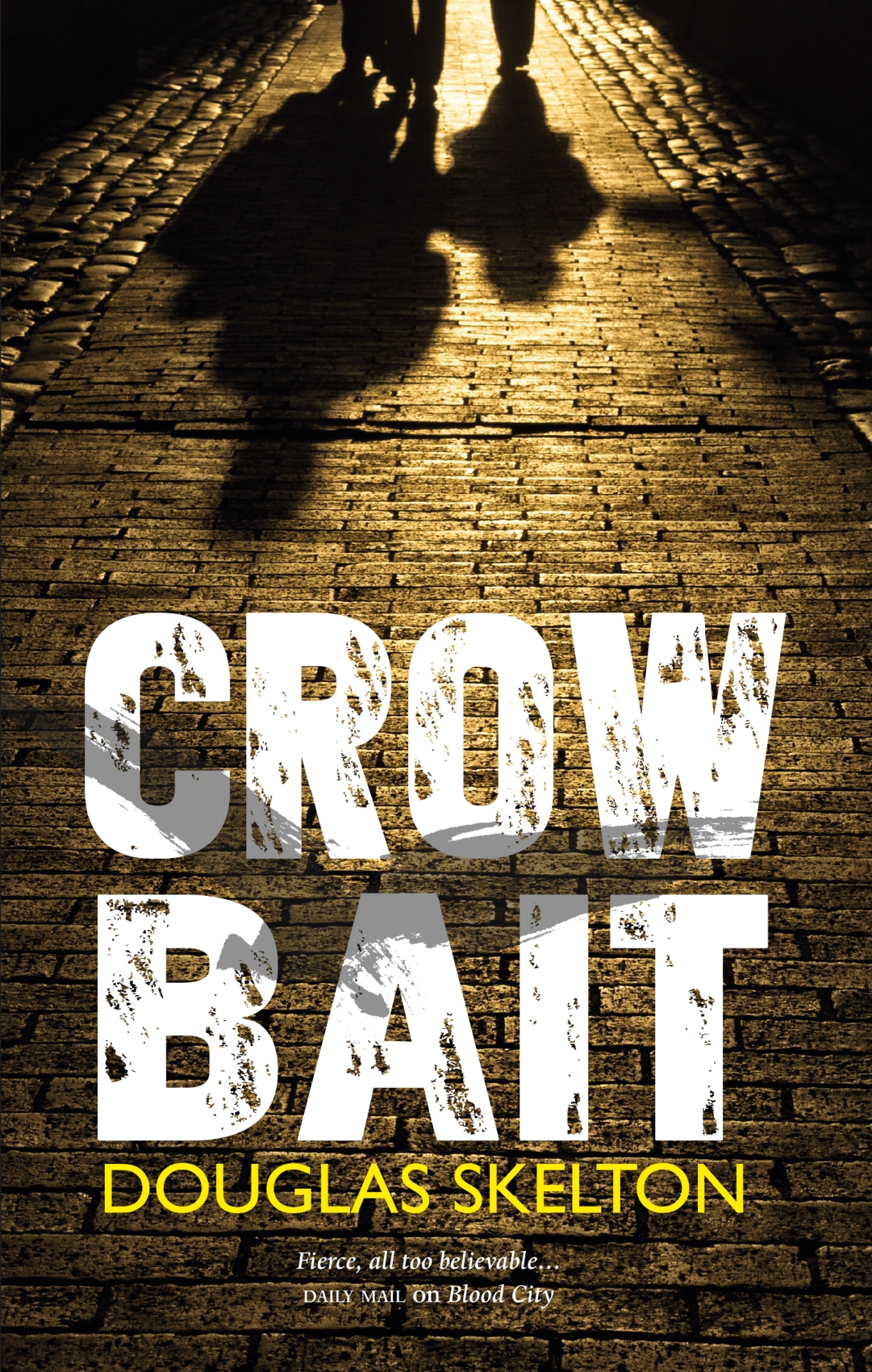

Crow Bait

DOUGLAS SKELTON

is an established true crime author, penning eleven books including

Glasgow’s Black Heart

,

Frightener

and

Dark Heart

. He has appeared on a variety of documentaries and news programmes as an expert on Glasgow crime, most recently on ‘Glasgow’s Gangs’ for the Crime and Investigation Channel with Martin and Gary Kemp. His 2005 book

Indian Peter

was later adapted for a

BBC

Scotland radio documentary, which he presented. His first foray into crime fiction was the acclaimed

Blood City

, which introduced Davie McCall.

By the same author:

Non-fiction

Blood on the Thistle

Frightener: The Glasgow Ice Cream wars

(with Lisa Brownlie)

No Final Solution

A Time to Kill

Devil’s Gallop

Deadlier than the Male

Bloody Valentine

Indian Peter

Scotland’s Most Wanted

Dark Heart

Glasgow’s Black Heart

Fiction

Blood City

DOUGLAS SKELTON

Luath

Press Limited

EDINBURGH

First published 2014

ISBN (PBK)

: 978-1-910021-29-3

ISBN (EBK): 978-1-910324-31-8

The publishers acknowledge the support of

Creative Scotland

towards the publication of this volume.

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Douglas Skelton 2014

Contents

Some other books published by LUATH PRESS

To the memories of

Edward Boyd and Roddie McMillan.

I never met them, but Daniel Pike showed me that a crime thriller did not need to be set in New York,

la

or London.

Glasgow’s mean streets would do just fine.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to my ‘Reading Posse’ – Karin Stewart, Sandy Kilpatrick, Lucy Bryden and Alistair and Rachel Neil.

To Big Stephen Wilkie, Joe Jackson and John Carroll for keeping me right. If I’ve made errors, they’re all mine.

To Elizabeth and Gary McLaughlin for their unflagging support in getting the books publicised (here’s another one, guys – get cracking.) And Helena Morrow for keeping Canada supplied.

To Margaret, for keeping me fed while I struggled with the rigours of writing.

To Caron MacPherson and Michael J. Malone for their advice, Alex Gray for saying nice things, and Craig Robertson for the support.

To my editor, Louise Hutcheson, and the team at Luath for making real what always begins as some vague notion as I walk the dogs.

For certain background information on the drug scene in 1990, I am indebted to a series of articles in the Glasgow

Evening Times

during October of that year by Mike Hildrey and Ally McLaws.

And thanks are due to the Steele boys, Jim and Joe.

Prologue

THE BOY IS

running across a field, the long grass around him sighing softly as a warm breeze whispers through its stalks. He is running, yet he moves slowly, like a film being played back at half-speed.

The boy is happy. It is a good day, the best day ever, and his young heart sings with its joy. They have taken him out of the city, away from the black buildings, away from the stench of the traffic, away from the constant roar of engines. A day in the country, where the sun didn’t need to burn through varying levels of grime to warm the land. His first day in the country and he revels in the feel of the soft grass caressing his legs as he runs.

He can see them waiting for him at the far end of the field, the car his father has borrowed from his boss parked under trees behind them. They smile at him as he draws nearer and his father wraps his arm around his mother’s waist. He gives the boy a friendly wave. It is a tender moment and the boy is sorry the day has to end.

But the air cools as the gap between them narrows and the field darkens as if a cloud has passed over the sun. The boy looks up, but the sun is still there, burning brightly in an unbroken blue sky. And yet, the day has shadowed and the grass has lost its colour. The green and sun-bleached yellow is gone, replaced by blacks and greys.

The boy stops and looks to his parents for an explanation, but they are no longer there. In their place is a dark patch, a deep red crying out amid the now muted surroundings, and the boy knows what has caused it.

‘Dad, don’t…’ he hears himself say.

‘Dad, please don’t…’ he murmurs as he backs away, fearful of what he might see in that pool of crimson. His mother, he now knows, is gone, never to return. But he also knows his father is there, somewhere in the red-stained darkness, waiting, watching.

So he backs away and he begins to turn, all the joy replaced by a deep-seated dread. He retreats, for all he wants to do now is get away from that corner of the field, and the sticky redness of the grass, so he turns to run, he turns to flee, he turns to hide.

But when he turns he finds his father looming over him, the poker raised above his head, the love he had once seen in the man’s eyes gone and in its place something else, something the boy does not fully understand, but something he knows will haunt him for the rest of his life. Something deadly, something inhuman.

And then his father brings the poker swinging down…

* * *

Barlinnie Prison

One night in November, 1990

Davie McCall woke with a start and for a moment he was unsure of his surroundings. Then, slowly, the grey outline of his cell, what he had come to call his

peter

, began to take shape and the night-time sounds of the prison filtered through his dream-fogged brain: Old Sammy snoring softly in his bed; the hollow echo of a screw walking the gallery; the coughs and occasional cries of other inmates as they struggled with their own terrors.

He had not had the dream for years, but now it had returned. The field was real and he had run through it on just such a warm summer day when his mum and dad took him to the Campsie Hills to the north of Glasgow when he was eight. They had been happy then. They had been a family then. It ended seven years later.

Danny McCall vanished when Davie was fifteen.

But the son knew the father was still out there, somewhere.

He had seen him, just once, little more than a fleeting glimpse, a blink and he was gone. It had been ten years before outside a Glasgow courthouse, just as Davie was being led away. He could not be sure for it was just a flash, but the more he replayed it in his mind, the clearer the face became, as if someone had tweaked the focus. It became a face he knew as well as his own, for the son was the image of the father. It bore a smile on the lips yet there was a coldness in the blue eyes.

And then, just as Davie was pulled away, a wave. He had not registered it at the time but as the months passed and he replayed the scene in his mind, he became sure of it. A wave that said

I’m back

.

1

IT WAS A

small room in a small flat and the glow of the electric fire stained the walls blood red. They used to call these one-roomed flats single ends, but that was before the estate agents moved in. Now they were studio apartments, to make them more attractive to the upwardly mobile. Not that the yuppies would be interested in this one. An enthusiastic salesman might call it a fixer upper, but really the only thing that would fix this place up was a canister of petrol and a match. It was run down, on its uppers. If this room had been a person, it would be homeless.

The wallpaper had been slapped on its walls back in the ’70s, when garish was good. Bright orange broken up by black wavy lines and the light radiating from the three bar electric fire made it look like the flames of hell. The furniture – what there was of it – would have given items thrown on a rubbish skip delusions of grandeur: a lumpy, stained two-seater settee, a matching armchair, the back bleeding stuffing, an old kitchen table, two wooden chairs, one lying on its side. A standard lamp, the bulb smashed, also on the floor. An ironing board, open and standing, a man’s shirt still hanging from the edge, the iron itself disconnected from the mains and discarded on the threadbare rug. There was a small kitchen area in the corner – a grime-encrusted cooker, a stained sink, a small fridge that looked incongruously new. The unmade single bed in the recess had clean, if rumpled linen, so someone was choosy about what they slept in.

It wasn’t the decor that obsessed the men and women moving to and fro. It was the woman on her back behind the table. A heavy poker lay in a pool of blood beside her. There was more blood caked on the frayed carpet, spattered on the walls and streaked on the ceiling. The woman’s face was a pulpy mass of battered tissue.