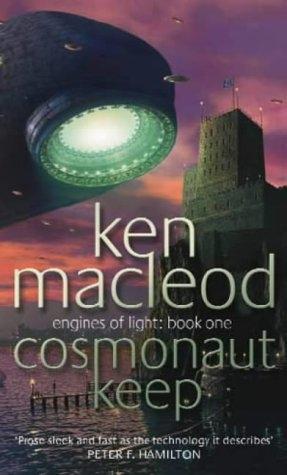

Cosmonaut Keep

Authors: Ken Macleod

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #Life on Other Planets, #Human-Alien Encounters, #Space Colonies, #High Tech

Cosmonaut Keep

Ken Macleod, 2001

and one of the chiefe trees or posts at the right side of the entrance had the barke taken off, and 5 foote from the ground in fayre Capitall letters was graven CROATOAN without any crosse or signe of distresse

0

____________

Prologue

You're not here. Try to remember this. Try not to remember where you really are.

You are in a twisty maze of dark corridors, all alike. You slide down the last of them as smoothly as a piston in a syringe, and are then ejected into the suddenly overwhelming open space of the interior. Minutes ago, you saw outer space, the universe, and the whole shebang itself didn't look bigger than this. Outer space is, fundamentally, familiar. It's only the night sky, without the earth beneath your feet.

This place is fundamentally unfamiliar. It's twenty miles long and five high and it's bigger than anything you've ever seen. It's a room with a world inside it.

To them, it's a bright world. To us it's a dark, cold cavern. To them, our most delicate probes would be like some gigantic spaceship hovering on rocket jets over one of our cities, playing searchlights of intolerable brightness across everything. That's why we're seeing it through their eyes, with their instruments, in their colors. The translation of the colors has more to do with emotional tone than the electromagnetic spectrum; a lot of thought, ours and theirs, has gone into this interpretation.

So what you see is a warm, rich green background, speckled with countless tiny, lively shapes in far more colors than you have names for. You think of jewels and hummingbirds and tropical fish. In fact the comparison with rainforest or coral reef is close to the mark. This is an ecosystem more complex than that of the whole Earth. As the viewpoint drifts closer to the surface you recall pictures of cities from the air, or the patterns of silicon circuitry. This, too, is apt: here, the distinction between natural and artificial is meaningless.

The viewpoint zooms in and out: from fractal snowflakes, rainbow-hued, in kaleidoscopic motion, to the vast violet-hazed distances and perspectives of the habitat, making clear the multiplicity and diversity of the place, the absence of repetition. Everything here is unique; there are similarities, but no species.

You can't shut it off; silently, relentlessly, the viewpoint keeps showing you more and more, until the inhuman but irresistible beauty of the alien garden or city or machine or mind harrows your heart. It will not let you go, unless you bless it; then, just as you fall into helpless love with it, it expels you, returning you to your humanity, and the dark.

1

____________

Ship Coming In

A god stood in the sky high above the sunset horizon, his long white hair streaming in the solar wind. Later, when the sky's color had shifted from green to black, the white glow would reach almost to the zenith, its light outshining the Foamy Wake, the broad band of the Galaxy. At least, it would if the squall-clouds scudding in off the land to the east had cleared by then. Gregor Cairns turned his back on the

C. M. Yonge's

own foamy wake, and looked past the masts and sheets at the sky ahead. The clouds were blacker and closer than they'd been the last time he'd looked, a few minutes earlier. Two of the lugger's five-man crew were already swinging the big sail around, preparing to tack into the freshening wind.

Much as he'd have liked to help, he knew from experience that he'd only get in the way. He turned his attention back to the tanks and nets in which the day's haul snapped, slapped, or writhed. Trilobites and ostracoderms, mostly, with a silvery smattering of teleostean fish, a slimy slither of sea-slugs, and crusty clusters of shelled molluscs and calcichordates. To Gregor this kind of assemblage was beginning to look incongruous and anachronistic; he grinned at the thought, reflecting that he now knew more about the marine life of Earth's oceans than he did of the planet whose first human settlers had long ago named Mingulay.

His wry smile was caught by his two colleagues, one of whom smiled back. Elizabeth Harkness was a big-boned, strong-featured young woman, about his own age and with a centimeter or two of advantage in height. Under a big leather hat her rough-cut black hair was blown forward over her ruddy cheeks. Like Gregor, she wore a heavy sweater, oilskins, rubber boots, and gauntlets. She squatted a couple of meters away on the laden afterdeck, probing tangles of holdfast with a rusty old knife, expertly slinging the separated molluscs, calcichordates, and float-wrack into their appropriate tanks.

"Come on," she said, "back to work."

"Aye," said Gregor, stooping to cautiously heave a ten-kilogram trilobite, scrabbling and snapping, into a water-filled wooden trough. "The faster we get this lot sorted, the more time for drinks back at the port."

"Yeah, so don't stick with the easy stuff." She flung some surplus mussels to the seabats that screamed and wheeled around the boat.

"Huh." Gregor grunted and left the relatively rugged trilobites to fend for themselves in the netting and creels while he pitched in to deal with the small shelly fauna. The vessel rolled, slopping salt water from the troughs and tanks, and then freshwater from the sky hissed onto the deck as they met the squall. He and Elizabeth worked on through it, yelling and laughing as their sorting became less and less discriminatory in their haste.

"As long as they don't

eat

each other ... "

The third student on the boat squatted opposite the two humans, knees on a level with his broad cheekbones, oblivious to the rain pelting his hairless head, and to the rivulets that trickled down his neck then over the seamless collar of his dull gray insulation-suit. The nictitating membranes of his large black eyes, and an occasional snort from his small nostrils or spit from his thin-lipped, inch-wide mouth were the only indications that the downpour affected him at all. His hands each had three long fingers and one long thumb; each digit came equipped with a claw that made a knife, for this task at least, quite unnecessary.

Gregor eyed him covertly, admiring the machinelike ease with which the long fingers sorted through the heaps; tangles ahead of them, neatly separated columns behind; the butchering strength and surgical skill and clinical gentleness of thumb and claw and palm. Then, answering some accurate intuition, the saur rocked back on his heels, washed his hands in the last of the rain, and stood up with his part of the task complete.

Elizabeth and Gregor looked at each other across a diminished area of decking on which nothing but stains and shreds of wrack remained. Elizabeth blinked wet lashes.

"Done," she said, standing up and shaking rain off her hat.

"Great." Gregor heaved himself upright and did likewise, joining the other two at the stern rail. They leaned on it, gazing out at the reddening sky in which the god glowed brighter. The highest clouds in the sky -- far higher than the squall-clouds -- shone with a peculiar mother-of-pearl rainbow effect, a rare phenomenon that had even the sailors murmuring in amazed appreciation.

Behind them the big sail came rattling down, and the engine coughed into life as the steersman took them in toward the harbor. The cliffs of a hundred-meter-high headland, crowned with a craggy castle, the Keep of Aird, rose on the port side; lower green hills and fields spread out to starboard. Ahead the lights were coming on in Kyohvic, the main port of the straggling seaboard republic known as the Heresiarchy of Tain.

"Good work, Salasso," Gregor said. The saur turned and nodded gravely, his nostrils and lips minutely twitching in his species' equivalent of a smile. Then the great black eyes -- their sides easily visible in profile -- returned to scanning the sea.

Salasso's long arm and long forefinger pointed.

"Teuthys,"

he hissed.

"Where?" Elizabeth cried, delighted. Gregor shaded his eyes and stared along the white wake and across the dark waves, so much of it there was, until he saw a darker silhouette rise, humping out of the water about a mile away. For a moment, so it remained, an islet in the deep.

"Could be just a whale -- " he murmured.

"Teuthys,"

the saur insisted.

The hump sank back and then a vast shape shot out of the surface, rising in an apparently impossible arc on a brief white jet; a glimpse of splayed tentacles behind the black wedge of the thing, then a huge splash as it planed back into the water. It did it again, and this time it wasn't black -- in its airborne second it glowed and flashed with flickering color. And it wasn't alone -- another kraken had joined it. They leaped together, again and then again, twisting and sporting. With a final synchronized leap that lasted two seconds, and a multicolored flare that lit the water like fireworks, the display ended.

"Oh, gods above," Elizabeth breathed. The saur's mouth was a little black O, and his body trembled. Gregor stared at where the krakens had played, awed but wondering. That they were playing he was certain, without knowing why. There were theories that such gratuitous expenditures of energy by krakens were some kind of mating display, or even ritual, but like most biologists Gregor regarded such hypotheses as beneath consideration.

"Architeuthys extraterrestris sapiens,"

he said slowly. "Masters of the galaxy. Having fun."

The saur's black tongue flickered, then his lips once more became a thin line.

"We do not know," he said, his words perhaps weightier, to Gregor, than he intended. But the man chose to treat them lightly, leaning out and sharing an aching, helpless grin with the woman.

"We don't know," he agreed, "but one day we'll find out." He jerked his face upward at the flare of white spreading up the sky. "Even the gods play, I'm sure of that. Why else would they leave their ... endless peace between the stars, and plunge between our worlds and swing around the sun?"

Salasso's neck seemed to contract a little; he averted his eyes from the sky, shivering again. Elizabeth laughed, not noticing or perhaps not reading the saur's subtle body-language. "Gods above, you can talk, man!" she said. "You think we'll ever know?"

"Aye, I do," said Gregor. "That's

our

play."

"Speak for yourself, Cairns, I know what mine is after a long hard day, and I'm" -- she glanced over her shoulder -- "about ten minutes from starting it with a long hard drink!"

Gregor shrugged and smiled, and they all relaxed, gazing at the sea and chatting. Then, as the first houses of the harbor town slipped by, one of the crewmen startled them with a loud, ringing cry:

"Ship coming in!"

Everybody on the boat looked up at the sky.

James Cairns stood, huddled in a fur cloak, on the castle's ancient battlement and gazed at the ship as it slid across the sky from the east, a glowing zeppelin at least three hundred meters long. Down the dark miles of the long valley -- lighting the flanks of the hill -- and over the clustered houses of the town it came, its course as steady and constant as a monorail bus. As it passed almost directly overhead at a thousand meters, Cairns was briefly amused to see that among the patterns picked out in lights on its sides were the squiggly signature-scribble of Coca-Cola; the double-arched golden

M;

the brave checkered banner of Microsoft; the Stars and Stripes; and the thirteen stars -- twelve small yellow stars and one central red star on a blue field -- of the European Union.

He presumed the display was supposed to provide some kind of reassurance. What it gave him -- and, he did not doubt, scores of other observers -- was a pang of pride and longing so acute that the shining shape blurred for a second. The old man blinked and sniffed, staring after the craft as its path sloped implacably seaward. When it was a kilometer or so out to sea, and a hundred meters above the water, a succession of silver lens-shaped objects scooted away from its sides, spinning clear and then heading back the way the ship had come. They came sailing in toward the port as the long ship's hull kissed the waves and settled, its flashing lights turning the black water to a rainbow kaleidoscope. Other lights, underwater and much smaller but hardly less bright, joined it in a colorful flurry.

Cairns turned his attention from the ship to its gravity skiffs; some swung down to land on the docks below, most skittered overhead and floated down, rocking like falling leaves, to the grassy ridge of the long hill that sloped down from the landward face of the castle. James strolled to the other side of the roof to watch. Somewhere beneath his feet, a relief generator hummed. Floodlights flared, lighting up the approach and glinting off the steely sides of the skiffs.

Almost banally after such a bravura arrival, the dozen or so skiffs had extended and come to rest on spindly telescoped legs; in their undersides hatches opened and stairladders emerged, down which saurs and humans trooped as casually as passengers off an airship. Each skiff gave forth two or three saurs, twice or thrice that number of humans; about a hundred in all walked slowly up the slope and onto the smoother grass of the castle lawns, tramping across it to be greeted by, and to mingle with, the castle's occupants. The gray-suited saurs looked more spruce than the humans, most of whom were in sea-boots and oilskins, dripping wet. The humans toward the rear were hauling little wheeled carts behind them, laden with luggage.

He felt a warm arm slide through the side-slit of his cloak and clasp his waist.

"Aren't you going down?" Margaret asked.

Cairns turned and looked down at his wife's eyes, which shone within a crinkle of crow's-feet as she smiled, and laid his right arm, suddenly heavy, across her shoulders.

"In a minute," he said. He sighed. "You know, even after all this time, that's still the sight that leaves me most dizzy."

Margaret chuckled darkly. "Yeah, I know. It gets me that way too."

Cairns knew that if he dwelt on the strangeness of the sight, the feeling of unreality could make him physically nauseous:

la nausée,

Sartre's old existential insecurity -- Cairns wondered, not for the first time, how the philosopher would have coped with a situation as metaphysically disturbing as this.