Complete Works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (217 page)

Read Complete Works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky Online

Authors: Fyodor Dostoyevsky

It was in winter that I arrived at the prison, and it was on the anniversary of that winter’s day that I was to be released.

Oh, with what impatience I looked forward to that thrice-blessed winter! How gladly I watched the summer fade, the leaves turn yellow on the trees, and the grass dry out over the wide steppe! Summer is gone at last! The winds of autumn howl and groan, the first snow falls in whirling flakes. The winter, so long, long prayed for, is come, come at last. Oh, how the heart beats with the thought that freedom is really, at last, at last, close at hand. Yet, strange to say, as the time; of times, the day of days, drew near, so did my soul become more tranquil. I was annoyed at myself, and even reproached myself with being cold, indifferent. Many of the convicts whom I met in the courtyard when the day’s work was done used to stop and talk with me to wish me joy.

‘Ah, Alexander Petrovitch, you’ll soon be free now! And you’ll be leaving us poor devils behind!’

‘Well, Mertynof, have you long to wait?’ I asked the man’ who spoke.

‘I! Oh, good Lord, I’ve seven years of it yet to weary through.’

The poor fellow sighed with a far-away, wandering look, as if gazing into those intolerable days to come… Yes, many of my companions congratulated me in a way that showed they really meant what they said. I saw, too, that they were more ready to address me as man to man; they drew nearer to me as I was about to leave them. The halo of freedom began to surround me, and because of that they esteemed me the more. It was in this spirit that they bade me farewell.

Kschniski, a young Polish noble, a sweet and amiable person, was very fond, at about this time, of walking in the courtyard with me. The stifling nights in barracks did him much harm, so he tried to preserve his health by taking all the exercise and fresh air he could.

‘I am looking forward impatiently to the day of your; release,’ he said with a smile one day, ‘for when you go I shall realize that I have just one more year to do.’

I need hardly say, though say it I must, that the prospect of freedom was for us prisoners something more than the reality. That was because our fancy constantly dwelt upon it. Prisoners always exaggerate when they think of freedom and see a free man. We certainly did: the poorest servant of one of the officers seemed to us like a king; compared with ourselves he was our ideal of the free man. He had no irons on his limbs, his head was not shaven, he could go where and when he liked with no soldiers to watch and escort him.

The day before my release, as night fell, I went

for the last time

all through and all round the prison. How many thousand times had I made the circuit of those palisades during those ten years! There, at the rear of the barracks, I had walked to and fro during the whole of that first year, a solitary, despairing man. I remember how I used to reckon up the days I had still to pass there-thousands, thousands! God, how long ago it seemed! Here the corner where the poor wounded eagle pined away; Petroff used often to join me there. It seemed now as if he would never leave me; he would walk along at my side without speaking a word, as though he knew all my thoughts as well as myself, and there was always a strange, inexplicable, wondering look on the man’s face.

How many a secret farewell I took of the black, squared beams in our barrack-room! Alas! how much joyless youth, how much fruitless strength was lost and buried in those walls!-youth and strength of which the world might surely have made some use. I cannot help expressing my conviction that amongst that hapless throng there were perhaps the strongest and, in some respects, the most gifted of our people. There was all that strength of body and of mind lost, hopelessly lost. Whose fault is that?

Yes. Whose fault is that?

Early next day, before the men were mustered for work, I went through every barrack to bid them a last farewell. Many a vigorous, horny hand was held out to me with right goodwill. Some grasped and shook my hand as though all their hearts were in the act; they were the more generous souls. Most of the poor fellows seemed to consider me as already changed by my impending good fortune, and, indeed, they could scarcely have felt otherwise. They knew that I had friends in the town, that I was leaving at once to mix with

gentlemen,

at whose tables I should sit as their equal. Of this the poor fellows were acutely conscious, and, although they did their best as they took my hand, that hand could never be the hand of an equal. No; I, too, was a gentleman from now. Some turned their back on me, and made no reply to my parting words. I think, moreover, that I saw

unfriendly looks on certain faces.

The drum beat; the convicts went to work, and I was left to myself. Souchiloff had risen before anyone else that morning, and now set himself tremblingly to the task of preparing me a final cup of tea. Poor Souchiloff! How he cried when I gave him my clothes, my shirts, my trouser straps, and some money.

“Tain’t that, ‘tain’t that,’ he said, and bit his trembling lips, ‘it’s that I am going to lose you, Alexander Petrovitch. What shall I do without you?’

Then there was Akim Akimitch; him, also, I bade farewell

‘Your turn will come soon, I hope,’ said I.

‘Ah, no! I shall remain here long, long, very long yet, he just managed to say as he pressed my hand. I threw myself on his neck; we kissed.

Ten minutes after the convicts had departed, my companion and I left the jail ‘for ever.’ We went to the blacksmith’s shop, where our irons were struck off. We had no armed escort, but were attended by a single N.C.O. Convicts struck off our irons in the engineers’ workshop. I let them do it for my friend first, then went to the anvil myself. The smiths made me turn round, seized my leg, and stretched it on the anvil. Then they went about their business methodically, as though they wanted to make a perfect job of it.

‘The rivet, man, turn the rivet first,’ I heard the master smith say; ‘there, so, so. Now, a stroke of the hammer!’

The irons fell. I lifted them up. Some strange impulse made me long to have them in my hands for the last time. I could not realize that only a moment before they had encircled my limbs.

‘Good-bye! Good-bye! Good-bye!’ said the convicts in their broken voices; but they seemed pleased as they said it.

Yes, farewell!

Liberty! New life! Resurrection from the dead!

Unspeakable moment!

THE END

Translated by Constance Garnett

The Notes from Underground

was published in 1864 and is considered by many to be the world’s first existentialist novel. It presents itself as an excerpt from the rambling memoirs of a bitter, isolated, unnamed narrator (generally referred to by critics as the Underground Man) who is a retired civil servant living in St. Petersburg. The first part of the story is related in monologue form, savagely attacking emerging Western philosophy, especially Nikolay Chernyshevsky's

What Is to Be Done?

The second part of the novella is called

Àpropos of the Wet Snow

and describes certain events that, it seems, are destroying and sometimes renewing the Underground Man, who acts as a first person, unreliable narrator.

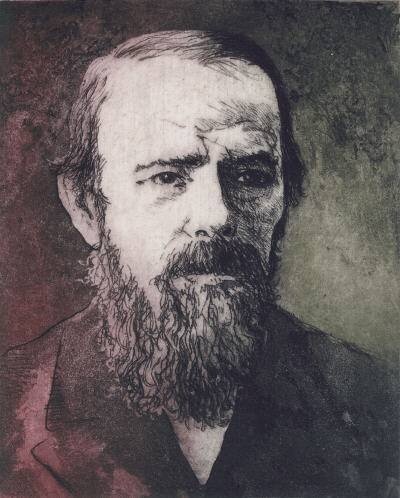

An illustration of Dostoyevsky, c. 1865

NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

CONTENTS

PART II. A PROPOS OF THE WET SNOW

PART I. UNDERGROUND

*The author of the diary and the diary itself are, of course, imaginary. Nevertheless it is clear that such persons as the writer of these notes not only may, but positively must, exist in our society, when we consider the circumstances in the midst of which our society is formed. I have tried to expose to the view of the public more distinctly than is commonly done, one of the characters of the recent past. He is one of the representatives of a generation still living. In this fragment, entitled “Underground,” this person introduces himself and his views, and, as it were, tries to explain the causes owing to which he has made his appearance and was bound to make his appearance in our midst. In the second fragment there are added the actual notes of this person concerning certain events in his life. — AUTHOR’S NOTE.

CHAPTER I

I am a sick man.... I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased. However, I know nothing at all about my disease, and do not know for certain what ails me. I don’t consult a doctor for it, and never have, though I have a respect for medicine and doctors. Besides, I am extremely superstitious, sufficiently so to respect medicine, anyway (I am well-educated enough not to be superstitious, but I am superstitious). No, I refuse to consult a doctor from spite. That you probably will not understand. Well, I understand it, though. Of course, I can’t explain who it is precisely that I am mortifying in this case by my spite: I am perfectly well aware that I cannot “pay out” the doctors by not consulting them; I know better than anyone that by all this I am only injuring myself and no one else. But still, if I don’t consult a doctor it is from spite. My liver is bad, well — let it get worse!

I have been going on like that for a long time — twenty years. Now I am forty. I used to be in the government service, but am no longer. I was a spiteful official. I was rude and took pleasure in being so. I did not take bribes, you see, so I was bound to find a recompense in that, at least. (A poor jest, but I will not scratch it out. I wrote it thinking it would sound very witty; but now that I have seen myself that I only wanted to show off in a despicable way, I will not scratch it out on purpose!)

When petitioners used to come for information to the table at which I sat, I used to grind my teeth at them, and felt intense enjoyment when I succeeded in making anybody unhappy. I almost did succeed. For the most part they were all timid people — of course, they were petitioners. But of the uppish ones there was one officer in particular I could not endure. He simply would not be humble, and clanked his sword in a disgusting way. I carried on a feud with him for eighteen months over that sword. At last I got the better of him. He left off clanking it. That happened in my youth, though.

But do you know, gentlemen, what was the chief point about my spite? Why, the whole point, the real sting of it lay in the fact that continually, even in the moment of the acutest spleen, I was inwardly conscious with shame that I was not only not a spiteful but not even an embittered man, that I was simply scaring sparrows at random and amusing myself by it. I might foam at the mouth, but bring me a doll to play with, give me a cup of tea with sugar in it, and maybe I should be appeased. I might even be genuinely touched, though probably I should grind my teeth at myself afterwards and lie awake at night with shame for months after. That was my way.

I was lying when I said just now that I was a spiteful official. I was lying from spite. I was simply amusing myself with the petitioners and with the officer, and in reality I never could become spiteful. I was conscious every moment in myself of many, very many elements absolutely opposite to that. I felt them positively swarming in me, these opposite elements. I knew that they had been swarming in me all my life and craving some outlet from me, but I would not let them, would not let them, purposely would not let them come out. They tormented me till I was ashamed: they drove me to convulsions and — sickened me, at last, how they sickened me! Now, are not you fancying, gentlemen, that I am expressing remorse for something now, that I am asking your forgiveness for something? I am sure you are fancying that ... However, I assure you I do not care if you are....