Coming of Age in the Milky Way (33 page)

Read Coming of Age in the Milky Way Online

Authors: Timothy Ferris

Tags: #Science, #Philosophy, #Space and time, #Cosmology, #Science - History, #Astronomy, #Metaphysics, #History

The fossil record, however, soon began turning up evidence of creatures no longer to be found in the world today. The absence of their living counterparts presented a challenge to advocates of the biblical account of history, who had maintained, relying upon Scriptures, that all animals were created at the same time and that none had since become extinct. For a while it was argued that living specimens of the unfamiliar species might yet survive, in distant lands to which they had migrated in the years since the strata were formed. Thomas Jefferson entertained this possibility and urged naturalists headed west to look for wooly mammoths, whose roar one pioneer had reported hearing echoing through the forests of Virginia. But as the years passed the world’s wildernesses were ever more thoroughly explored, and still no sign of the mammoth or its lost cousins turned up. Meanwhile, the roster of missing species grew longer—Georges Cuvier, the French zoologist who founded the science of paleontology, had by 1801 identified twenty-three species of extinct animals in the fossil record—and the word “extinct” began tolling like a bell in the scientific literature and the university lecture halls. It has gone on tolling ever since; and today it is understood that 99 percent of all the species that have lived on the earth have since died out.

Almost as troublesome to Christian interpreters of the earth’s history was the bewildering variety of

living

species being discovered by biologists in their laboratories and by naturalists exploring the jungles of Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia. Some, like the giant subtropical beetles that bit the young Darwin, were noxious; their benefit to humanity, for whom God was said to have

made the world, was not immediately evident. Many were so minuscule that they could be detected only with a microscope; their role in God’s plan had not been anticipated. Others were instinctively unsettling—none more so than the orangutan, whose name derives from the Malay for “wild man” and whose warm, almost intimate gaze, coming as it does from only a puddle or two across the primate gene pool, seemed to mock human pretensions of uniqueness. None of these creatures was thought to have shown up on the passenger’s roster of Noah’s arc. What were they doing here?

The religious orthodoxy took temporary refuge in the concept of a “Great Chain of Being.” This precept held that the hierarchy of living beings, from the lowliest microorganisms to the apes and great whales, had been created by God simultaneously, and that all, together, formed one marvelous structure, a magic mountain with humans at—or near—its apex. The importance of the Great Chain of Being in eighteenth-century thought is difficult to overestimate; it figured in the framing of most of the scientific hypotheses of the time. The Chain, however, was no stronger than its weakest link; its very completeness was itself proof of the perfection of God, and there could, therefore, be no “missing link.” (The term, later adopted by the evolutionists, began here.) As John Locke wrote:

In all the visible corporeal world we see no chasms or gaps. All quite down from us the descent is by easy steps, and a continued series that in each remove differ very little one from the other. There are fishes that have wings and are not strangers to the airy region, and there are some birds that are inhabitants of the water, whose blood is as cold as fishes…. When we consider the infinite power and wisdom of the Maker, we have reason to think that it is suitable to the magnificent harmony of the universe, and the great design and infinite goodness of the architect, that the species of creatures should also, by gentle degrees, ascend upwards from us towards his infinite perfection, as we see they gradually descend from us downwards.

7

Here resided the horror that the prospect of extinction elicited in the thoughts of the pious. “It is contrary to the common course of providence to suffer any of his creatures to be annihilated,” wrote

the Quaker naturalist Peter Collinson, as in awe he contemplated the mighty teeth of the extinct mastodon and the weighty bones of the equally extinct Irish elk.

8

The seventeenth-century naturalist John Ray noted that evidence of “the destruction of any one species,” would amount to “a dismembring of the Universe, and rendring it imperfect.”

9

Yet still the death knell tolled, as the geologists’ spades and the railroad builders’ steam shovels continued to turn up the remains of an ever increasing variety of organisms that clearly once had lived but were to be found no more. There was fossil evidence of flowers never known to have bloomed in human sight, bizarre fishes and birds that no one had ever seen swim or fly, and exotic creatures that could not fail to capture the popular as well as the scientific imagination—the saber-toothed tiger, the “dawn horse,” the giant armadillo, the woolly rhino, and the dinosaurs—all gone forever. And, since fossils of many of these creatures were found in climates where they could not have thrived (fish on mountaintops, polar bears in the tropics) the earth must have undergone profound and wide-reaching changes since the time when the extinct species had lived. How could all this have happened in the short span of Bishop Ussher’s six thousand years?

The most promising answer for the fundamentalists lay in what came to be called catastrophism, the hypothesis that such major geological changes as had occurred had come about suddenly, as the result of cataclysmic, almost supernatural upheavals that had leveled mountains, raised seabeds toward the sky, and doomed whole species to extinction almost overnight. Catastrophism accounted for the extinction of species in the fossil record without violating biblical chronology, and it enjoyed strong support from the biblical story of the Flood, which the catastrophists came to regard as but the most dramatic among several disasters visited upon the world by a wrathful God. As to the question of whether all these cataclysms had been divinely ordained there was some disparity of opinion, with Cuvier like many geologists in the early nineteenth century proposing that while the Lord had wrought the Flood and earlier disasters, the ones since might be ascribed to conventionally causal agencies.

From a scientific standpoint, the most pernicious implication of catastrophism was that it severed the past from the present, much as Aristotle’s astrophysics had divorced the aethereal from the mundane.

By relegating major geological changes to the action of preternaturally powerful forces that had manifested themselves only in the early history of the earth, catastrophism barred the extrapolation into history of scientific laws gleaned from the world today. “Never,” wrote the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell, “was there a dogma more calculated to foster indolence, and to blunt the keen edge of curiosity, than this assumption of the discordance between the former and the existing causes of change.”

10

Lyell held a contrary view, called uniformitarianism. He maintained that

all

geological and biological change was due to ordinary, natural causes that had operated in much the same way throughout the earth’s long history. The extinction of species, by uniformitarian lights, was brought about by events very much akin to those we see in action around us today—the slow erosion of rock and soil by wind and water, gradual changes in climate, and the occasional raising and lowering of mountains.

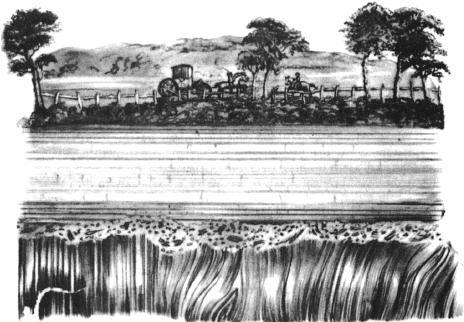

This steady-state view of the earth’s history had first been advanced by the Scottish chemist James Hutton. The Herschel of geological history, Hutton was a farsighted visionary who saw the imprint of aeons etched in common rocks: “The ruins of an older world are visible in the present structure of our planet,” he wrote. He illustrated his thesis with a cutaway drawing that depicted, above ground, a placid English countryside scene—an enclosed carriage drawn by two horses standing by a fence in the woods—while below stretched a frieze of strata, and, beneath that, a twisted and jumbled tableau of metamorphic rock, the frozen image of a tumultuous and ever changing world.

As change in a noncatastrophic world must on the whole proceed slowly, the uniformitarian hypothesis required that the earth be very old. There was some theoretical evidence that this might be the case: Georges Buffon, the French naturalist, had argued from astronomical premises that the earth began as a molten ball that slowly cooled, and that its age might therefore amount to as much as five hundred thousand years. Now Hutton, concerned not with the origin of the earth but with the geological processes to which it was currently being subjected, arrived at an even grander estimation of the extent of antiquity. “We find,” he wrote, “no vestige of a beginning,—no prospect of an end.”

11

This was daring, perhaps, but also reckless; an

infinite

past is a great deal more problematical than a very long past. (Darwin was to make a similar

mistake, arguing for an infinitely old Earth until his mathematician friends took him aside and explained that infinity is strong and dangerous medicine and not just a big number.)

Buried evidence of geological upheaval was depicted in cutaway drawings like this one in Hutton’s

Theory of the Earth

. (After Hutton, 1795.)

The inaugural fortunes of uniformitarianism suffered, moreover, from the liabilities of Hutton’s literary style; his

Theory of the Earth

, published in 1795, was written in a syntax as jumbled as the strata it described. The situation improved somewhat when John Playfair took the trouble to elucidate his friend Hutton’s views, in his

Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth

, but the real breakthrough came a generation later, when the uniformitarian hypothesis was taken up by Lyell. Born in 1797, the year of Hutton’s death, Lyell was an energetic young man, blessed with poor eyesight,

who peered at the world around him with myopic intensity. While still an undergraduate studying geology at Oxford, Lyell took a holiday trip to a spot on the seashore that he had visited as a child, and he noticed, as many another bather had not, that erosion had slightly altered the shape of the coastline near Norwich. He began to conceive of the planet as a seething, changing entity, writhing in its own good time like a living organism.

Much of the prior debate over the age of the world had been conducted from easy chairs, by the likes of the English divine Thomas Burnet, who boasted that he based his efforts to reconcile scientific and biblical accounts of history on but three sources, “Scripture, Reason, and ancient Tradition.”‘

12

Lyell spent his days wandering to and fro upon the earth, and in his sixties was still scrambling up mountainsides and down dry washes, making notes all the while. Mount Etna in Sicily, the traditional abode of Vulcan’s forge, had long been a favorite subject of studious scholars who had viewed it, if at all, from afar. Lyell climbed its slopes of freshly frozen lava, and deduced, from his measurements of the sheer bulk of the ten-thousand-foot mountain, that it had been built up from a great many lava flows, the accumulation of which “must have required an immense series of ages anterior to our historical periods for its growth.”

13

In Chile, Lyell estimated that a single earthquake could elevate the coastal mountains by as much as three feet, and speculated that “a repetition of two thousand shocks, of equal violence, might produce a mountain chain one hundred miles long and six thousand feet high.”

14

The identification of warm-water seashells in northern Italy and of the bodies of mammoth frozen in Siberian ice, he noted, indicate that the European climate was once “sufficiently mild to afford food for numerous herds of elephants and rhinoceroses,

of species distinct from those now living”

(Lyell’s italics).

15

A lucid and vivid writer, Lyell was as adept at demolishing the arguments of the catastrophists as he was at comprehending the construction of mountain ranges. “Geologists have been ever prone to represent Nature as having been prodigal of violence and parsimonious of time,” he wrote, but, he noted, the fracturing and weathering of rock taken by the catastrophists to represent the violence of the early Earth could as easily have been imposed by the ravages of time.

16

A voracious student of biology as well as geology (his father had been a botanist, and Lyell

fils

had studied

entomology) he drew upon the life sciences as well. The catastrophists relegate extinction to brief cataclysms, he wrote, but

if we then turn to the present state of the animate creation, and inquire whether it has now become fixed and stationary, we discover that, on the contrary, it is in a state of continual flux—that there are many causes in action which tend to the extinction of species, and which are conclusive against the doctrine of their unlimited durability.’

17