Coming into the Country (24 page)

Read Coming into the Country Online

Authors: John McPhee

Arliss Sturgulewski, offering berries from her hand, said as much, and shook her head, and looked long at the splendid landscapeâthe city siteâsloping down to the stream. “We need the right kind of planning before Dollar One is spent on the ground,” she said. “We need to take advantage of views âof the uniqueness of the settingâand then see to it that the capital is not just another place. You've got to take everything that you've learned and absorbed and make something out of it. You can't just quantify it. You need a gut feeling, and at least we get something of that standing here. I'm wondering who, in the end, will run this capital. What will the land use be, the zoning, the planning? Government is the catalyst at the beginning, but then may lose control.”

Loose flakes of gold hung in a clear amulet around her neck. Over her blouse was a Levi jacket. She was tall, large-boned,

attractive, blond. She came from the mountains of northern Washington and had been in Alaskaâin Anchorageâalmost twenty-five years. Her husband had died in an F-27 propjet on its way to King Salmon, and, in the seven years since, she had immersed herself in civic affairs, most notably as a member of the Greater Anchorage Area Planning and Zoning Commission. Like the Mrs. Partington who tried to fight the Atlantic Ocean with a mop, she had watched, and she had fought, the splurge of Anchorage.

attractive, blond. She came from the mountains of northern Washington and had been in Alaskaâin Anchorageâalmost twenty-five years. Her husband had died in an F-27 propjet on its way to King Salmon, and, in the seven years since, she had immersed herself in civic affairs, most notably as a member of the Greater Anchorage Area Planning and Zoning Commission. Like the Mrs. Partington who tried to fight the Atlantic Ocean with a mop, she had watched, and she had fought, the splurge of Anchorage.

Control had been lame as it followed development, she said. “Lots were ruled off on paper that for one reason or another could never be developed. Soil testing, the presence of adequate utilities were not required. For a long time, there was no control. When efforts at control came, they lacked force and lagged behind. There were no building codes. We finally got some codes, but not until 1972. There was no floodplain ordinance until 1975. There are sixty streams and rivers in the Anchorage Bowl. Before this year, there was development in the floodplains, and even in the floodways! Authorities had to approve development that was already built. The planning commission had no power. We were only advisory. We did get some positive things. We got bike trails. But in a boom situation your development really gets away from you. Twelve thousand new people have come to Anchorage in the past year. The streets are falling apart. We were unprepared for the impact of the pipeline. When a boom comes along, you don't have strong enough rules. You can't keep up. Now look at this place âhow beautiful it is. Can you imagine what could happen out here? Alaskans don't see the value of order, don't see the value of looking to the future.”

Â

Â

Â

We were about forty-five minutes from Anchorage, and the helicopter had forty minutes of remaining fuelâa condition

We were about forty-five minutes from Anchorage, and the helicopter had forty minutes of remaining fuelâa conditionthat would hardly arouse the interest of many Alaskan pilots, but ours was particularly careful, and he landed again at Skwentna, where he had a cache of fifty-five-gallon drums. The bloody moosemeat we had seen there earlier was gone. The gravel airstrip was as silent as it had been before. Out of a stand of fireweed, the pilot, Bill Brandt, rolled two drums. He set them on end by the helicopter. He knocked out a bung and smelled the contents. Never knew what might get into these barrels, he remarked, and he inserted a high-vacuum hand pump and began to work. He pumped hard. With beavery sideburns and a billowing glory of a mustache, he looked like an antique Alaskan, and all the more incongruous there pumping Chevron Jet Fuel into a big chopper. He grew tired, and Willie Hensley took over, pumping in an easy rhythm and half as hard.

In the air again, we flew southeast and soon over Bulchitna Lake, a capital-site possibility, its water so clear that we could see, in places, its white sand bottom, and blue-green fathoms where the sand was below the reach of light.

“Is that Bulchitna?” said Arliss Sturgulewski.

“Bulchitna, Alaska,” said Willie Hensley. “I propose that as the name of the capital.”

It was a lovely lake in a closed spruce-hardwood forest, and I would much have liked to see it from its shore, but the helicopter did not set down by it, or even give up altitude. C. B. Bettisworth said he thought the surrounding terrain too flat, and Earl Cook said he agreed. A pair of eagles flew out from the shoreline trees.

We flew on over a water-dispersed country of ponds and beaver houses, bogs, muskeg fairways, and across the big rivers âKahiltna, Susitnaâto an even greater spread of lakes. These, near Willow, had become a summering world for people from Anchorageâice out in May and swimming by Julyâmany of whom were now experiencing their own private spasms of the Alaskan paradox, the Dallas scenario versus the Sierra Club

syndrome. They worried about their country retreats while they watched the values rise. For beyond Willow, on the upland toward Hatcher Pass, in spruce-and-birch forest that gives way in a dramatic treeline to moors of alpine tundra, was a capital site perhaps more likely than all others to be the ultimate choice of voters. Its temperatures and altitude were much the same as they were at remote Mount Yenlo. Its viewsâof the valley and of the Alaska Range to the northâwere almost as good. The railroad and highway were close. A five-thousand-foot gravel airstrip, built for B-29s, stood ready for facilities and tarmac. Andâpoint of pointsâAnchorage was scarcely thirty miles away.

syndrome. They worried about their country retreats while they watched the values rise. For beyond Willow, on the upland toward Hatcher Pass, in spruce-and-birch forest that gives way in a dramatic treeline to moors of alpine tundra, was a capital site perhaps more likely than all others to be the ultimate choice of voters. Its temperatures and altitude were much the same as they were at remote Mount Yenlo. Its viewsâof the valley and of the Alaska Range to the northâwere almost as good. The railroad and highway were close. A five-thousand-foot gravel airstrip, built for B-29s, stood ready for facilities and tarmac. Andâpoint of pointsâAnchorage was scarcely thirty miles away.

Willow is still a hamletâthree hundred peopleâwith potatoes growing in surrounding clearings and tomato vines five feet high: the sort of place where it is not unknown, in the dead of winter, for an old moose hunter to die in his cabin and be brought into town frozen solid. I had stayed in Willow for a night or two, in a cabin that had no windows. Wadded paper filled the gaps in the logs. Twenty dollars a night, with heat. In the Willow Trading Post one morning, a man in a baseball suit was tending bar, and people sitting on stools there were talking about the five acres they had bought for two thousand dollars and how they had recently been offered fifty thousand dollars but were waiting for seventy-five. “OUR COW IS DEAD,” said a sign above them. “WE DON'T NEED YOUR BULL.” Just up the track was another, somewhat newer sign: “WILLOW BROOK ESTATES, A QUALITY DEVELOPMENT BY LANDAK, INC.”

In its meetings in following weeks, the committee would finally reduce its list to three sites that would appear on Alaskan ballots, and the three it would choose would be Larson Lake, near Talkeetna; Mount Yenlo, in the western valley; and the heights to the east of Willow. The site attracting the most votes would be the site of the new capital of Alaska, and when the election came, the emphatic preference of the voters would

prove to be Willow. By the terms of the initiative, the move was to begin by 1980. Opponents of the move would go on clinging to the hope that, come groundbreaking day, the money would not be there. Meanwhile, the big helicopter flew on into rain and falling darkness, down the short run to Alaska's principal cityâover Knik Arm, into the Bowl. The rain blurred the windows. Through them, the streets and buildings below appeared to be lying under ten layers of acetate. The chopper touched down. Earl Cook, who had left his home in Fairbanks at six in the morning, unbuckled his seat belt with a terminal sigh. “That ⦔ he said. “That's a hell of a way to get to Anchorage.”

prove to be Willow. By the terms of the initiative, the move was to begin by 1980. Opponents of the move would go on clinging to the hope that, come groundbreaking day, the money would not be there. Meanwhile, the big helicopter flew on into rain and falling darkness, down the short run to Alaska's principal cityâover Knik Arm, into the Bowl. The rain blurred the windows. Through them, the streets and buildings below appeared to be lying under ten layers of acetate. The chopper touched down. Earl Cook, who had left his home in Fairbanks at six in the morning, unbuckled his seat belt with a terminal sigh. “That ⦔ he said. “That's a hell of a way to get to Anchorage.”

COMING INTO THE COUNTRY

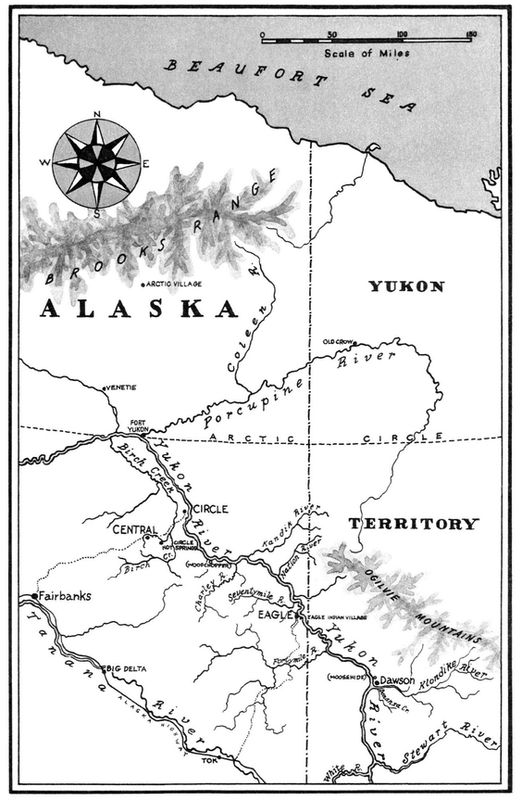

With a clannish sense of place characteristic of the bush, people in the region of the upper Yukon refer to their part of Alaska as “the country.” A stranger appearing among them is said to have “come into the country.”

With a clannish sense of place characteristic of the bush, people in the region of the upper Yukon refer to their part of Alaska as “the country.” A stranger appearing among them is said to have “come into the country.”Donna Kneeland came into the country in April, 1975. Energetically, she undertook to learn, and before long she had an enviable reputation for certain of her skills, notably her way with fur. Knowledgeable people can look at a pelt and say that Donna tanned it. In part to save money, she hopes to give up commercial chemicals and use instead the brains of animalsâto “Indian tan,” as she puts itâand she has found a teacher or two among the Indian women of the region, a few of whom remember how it was done. The fur is mainly for sale, and it is the principal source of support for her and her companion, whose name is Dick Cook. (He is not related to Earl Cook, of the Capital Site Selection Committee.) A marten might bring fifty dollars. Lynx, about three hundred. Wolf, two hundred and fifty. They live in a cabin half a dozen miles up a tributary stream, at least forty and perhaps sixty miles from the point on the border meridian where the Yukon River leaves Yukon

Territory and flows on into Alaska. The numbers are deliberately vague, because Cook and Kneeland do not want people to know exactly where the cabin is. Their nearest neighbors, a couple who also live by hunting and trapping, are something like twenty miles from them. To pick up supplies, they travel a good bit farther than that. They make a journey of a couple of days, by canoe or dog team, to Eagle, a bush community not far from the Canadian boundary whose population has expanded in recent years and now exceeds a hundred. For three-quarters of a century, Eagle has been an incorporated Alaskan city, and it is the largest sign of human material progress in twenty thousand square miles of rugged, riverine land. From big bluffs above the Yukonâfive hundred, a thousand, fifteen hundred feet highâthe country reaches back in mountains, which, locally, are styled as hills. The Tanana Hills. The tops of the hills are much the same height as New Hampshire's Mt. Washington, Maine's Mt. Katahdin, and North Carolina's Mt. Mitchell. Pebble-clear streams trellis the mountains, descending toward the opaque, glacier-fed Yukon, and each tributary drainage is suitable terrain for a trapper or two, and for miners where there is gold.

Territory and flows on into Alaska. The numbers are deliberately vague, because Cook and Kneeland do not want people to know exactly where the cabin is. Their nearest neighbors, a couple who also live by hunting and trapping, are something like twenty miles from them. To pick up supplies, they travel a good bit farther than that. They make a journey of a couple of days, by canoe or dog team, to Eagle, a bush community not far from the Canadian boundary whose population has expanded in recent years and now exceeds a hundred. For three-quarters of a century, Eagle has been an incorporated Alaskan city, and it is the largest sign of human material progress in twenty thousand square miles of rugged, riverine land. From big bluffs above the Yukonâfive hundred, a thousand, fifteen hundred feet highâthe country reaches back in mountains, which, locally, are styled as hills. The Tanana Hills. The tops of the hills are much the same height as New Hampshire's Mt. Washington, Maine's Mt. Katahdin, and North Carolina's Mt. Mitchell. Pebble-clear streams trellis the mountains, descending toward the opaque, glacier-fed Yukon, and each tributary drainage is suitable terrain for a trapper or two, and for miners where there is gold.

For Donna Kneeland, as many as five months have gone by without a visit to Eagle, and much of the time she is alone in the cabin, while her man is out on the trail. She cooks and cans things. She grinds wheat berries and bakes bread. She breaks damp skins with an old gun barrel and works them with a metal scraper. A roommate she once had at the University of Alaska went off to “the other states” and left her a hundred-and-fiftydollar Canadian Pioneer parka. She has never worn it, because âalthough her cabin is in the coldest part of Alaskaâwinter temperatures have yet to go low enough to make her feel a need to put it on. “We've had some cool weather,” she admits. “I don't know how cold, exactly. Our thermometer only goes to fifty-eight.” When she goes out at such temperatures to saw or

to split the wood she survives onâwith the air at sixty and more below zeroâshe wears a down sweater. It is all she needs as long as her limbs are active. Her copy of “The Joy of Cooking” previously belonged to a trapper's wife who froze to death. Donna's father, a state policeman, was sent in to collect the corpse.

to split the wood she survives onâwith the air at sixty and more below zeroâshe wears a down sweater. It is all she needs as long as her limbs are active. Her copy of “The Joy of Cooking” previously belonged to a trapper's wife who froze to death. Donna's father, a state policeman, was sent in to collect the corpse.

Donna is something rare among Alaskansâa white who is Alaska-born. She was born in Juneau, and as her father was biennially transferred from post to post, she grew up all over AlaskaâBarrow, Tok, Fairbanks. In girlhood summers, she worked in a mining camp at Livengood, cooking for the crew. At the university, which is in Fairbanks, she majored in anthropology. In 1974, she fell in love with a student from the University of Alberta, and she went off to Edmonton to be with him. Edmonton is Canada's fourth-largest city and is the size of Nashville. “In Edmonton, every place I went I could see nothing but civilization. I never felt I could ever get out. I wanted to see something with no civilization in it. I wanted to see even two or three miles of just nothing. I missed this very much. In a big city, I can't find my way out of a paper bag. I was scared to death of the traffic. I was in many ways unhappy. One day I thought, I know what I want to doâI want to go live in the woods. I left the same day for Alaska.”

In Alaska, where “the woods” are wildernesses beyond the general understanding of the word, one does not prudently just wander offâas Donna's whole life had taught her. She may have lived in various pinpoints of Alaskan civilization, but she had never lived out on her own. She went to Fairbanks first. She took a jobâwhite dress and allâas a dental assistant. She asked around about trappers who came to town. She went to a meeting of the Interior Alaska Trappers Association and studied the membership with assessive eyes. When the time came for a choice, she would probably have no difficulty, for she was a beautiful young woman, twenty-eight at the time,

with a criterion figure, dark-blond hair, and slate-blue, striking eyes.

with a criterion figure, dark-blond hair, and slate-blue, striking eyes.

Â

Â

Â

Richard Okey Cook came into the country in 1964, and put up a log lean-to not far from the site where he would build his present cabin. Trained in aspects of geophysics, he did some free-lance prospecting that first summer near the head of the Seventymile River, which goes into the Yukon a few bends below Eagle. His larger purpose, though, was to stay in the country and to change himself thoroughly “from a professional into a bum”âto learn to trap, to handle dogs and sleds, to net fish in quantities sufficient to feed the dogs. “And that isn't easy,” he is quick to say, claiming that to lower his income and raise his independence he has worked twice as hard as most people. Born and brought up in Ohio, he was a real-estate appraiser there before he left for Alaska. He had also been to the Colorado School of Mines and had run potentiometer surveys for Kennecott Copper in Arizona. Like many Alaskans, he came north to repudiate one kind of life and to try another. “I wanted to get away from paying taxes to support something I didn't believe in, to get away from big business, to get away from a place where you can't be sure of anything you hear or anything you read. Doctors rip you off down there. There's not an honest lawyer in the Lower Forty-eight. The only honest people left are in jail.” Toward those who had held power over him in various situations his reactions had sometimes been emphatic. He took a poke at his high-school principal, in Lyndhurst, Ohio, and was expelled from school. In the Marine Corps, he became a corporal twice and a private first class three times. His demotions resulted from fistfightsâon several occasions with sergeants, once with a lieutenant. Now he has tens of thousands of acres around him and no authorities ordinarily

Richard Okey Cook came into the country in 1964, and put up a log lean-to not far from the site where he would build his present cabin. Trained in aspects of geophysics, he did some free-lance prospecting that first summer near the head of the Seventymile River, which goes into the Yukon a few bends below Eagle. His larger purpose, though, was to stay in the country and to change himself thoroughly “from a professional into a bum”âto learn to trap, to handle dogs and sleds, to net fish in quantities sufficient to feed the dogs. “And that isn't easy,” he is quick to say, claiming that to lower his income and raise his independence he has worked twice as hard as most people. Born and brought up in Ohio, he was a real-estate appraiser there before he left for Alaska. He had also been to the Colorado School of Mines and had run potentiometer surveys for Kennecott Copper in Arizona. Like many Alaskans, he came north to repudiate one kind of life and to try another. “I wanted to get away from paying taxes to support something I didn't believe in, to get away from big business, to get away from a place where you can't be sure of anything you hear or anything you read. Doctors rip you off down there. There's not an honest lawyer in the Lower Forty-eight. The only honest people left are in jail.” Toward those who had held power over him in various situations his reactions had sometimes been emphatic. He took a poke at his high-school principal, in Lyndhurst, Ohio, and was expelled from school. In the Marine Corps, he became a corporal twice and a private first class three times. His demotions resulted from fistfightsâon several occasions with sergeants, once with a lieutenant. Now he has tens of thousands of acres around him and no authorities ordinarilyproximitous enough to threaten himâexcept nature, which he regards as God. While he was assembling his wilderness dexterity, he spent much of the year in Eagle, and he became, for a while, its mayor. A single face, a single vote, counts for a lot in Alaska, and especially in the bush.

The traplines Cook has established for himself are along several streams, across the divides between their headwaters and on both banks of the Yukonâupward of a hundred miles in all, in several loops. He runs them mainly in November and December. He does not use a snow machine, as many trappers in Alaska do. He says, “The two worst things that ever happened to this country are the airplane and the snow machine.” His traplines traverse steep terrain, rocky gulliesâplaces where he could not use a machine anyway. To get through, he requires sleds and dogs. Generally, he has to camp out at least one night to complete a circuit. If the temperature is colder than thirty below, he stays in his cabin and waits for the snap to pass. As soon as the air warms up, he hits the trail. He has built lean-tos in a few places, but often enough he sleeps where he gets tiredâunder an orange canvas tarp. It is ten feet by ten, and weighs two and a half pounds, and is all the shelter he needs at, say, twenty below zero. Picking out a tree, he ties one corner of the tarp to the trunk, as high as he can reach. He stakes down the far corner, then stakes down the two sides. Sometimes, he will loft the center by tying a cord to a branch above. He builds a lasting fire between the tree and himself, gets into his sleeping bag, and drifts away. Most nights are calm. Snow is light in the upper Yukon. The tarp's configuration is not so much for protection as to reflect the heat of the fire. He could make a closed tent with the tarp, if necessary. His ground cloth, or bed pad, laid out on the snow beneath him, is the hide of a caribou.

He carries dried chum salmon for his dogs, and his own food is dried moose or bear meat and pinoleâground parched corn, to which he adds brown sugar. In the Algonquin language,

pinole was “rockahominy.” “It kept Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett going. It keeps me going, too.” He carries no flour. “Flour will go rancid on you unless you buy white flour, but you can't live and work on that. I had a friend who died of a heart attack from eating that crap. It's not news that the American people are killing themselves with white flour, white sugar, and soda pop. If you get out and trap thirty miles a day behind dogs, you can damned well tell what lets you work and what doesn't.” From a supplier in Seattle he orders hundred-pound sacks of corn, pinto beans, unground wheat. He buys cases of vinegar, tomato paste, and tea. Forty pounds of butter in one-pound cans. A hundred pounds of dried milk, sixty-five of dried fruit. Twenty-five pounds of cashews. Twenty-five pounds of oats. A forty-pound can of peanut butter. He carries it all down the Yukon from Eagle by sled or canoe. He uses a couple of moose a year, and a few bear, which are easier to handle in summer. “A moose has too much meat. The waste up here you wouldn't believe. Hunters that come through here leave a third of the moose. Indians don't waste, but with rifles they are overexcitable. They shoot into herds of caribou and wound some. I utilize everything, though. Stomach. Intestines. Head. I feed the carcasses of wolverine, marten, and fox to the dogs. Lynx is another matter. It's exceptionally good, something like chicken or pork.”

pinole was “rockahominy.” “It kept Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett going. It keeps me going, too.” He carries no flour. “Flour will go rancid on you unless you buy white flour, but you can't live and work on that. I had a friend who died of a heart attack from eating that crap. It's not news that the American people are killing themselves with white flour, white sugar, and soda pop. If you get out and trap thirty miles a day behind dogs, you can damned well tell what lets you work and what doesn't.” From a supplier in Seattle he orders hundred-pound sacks of corn, pinto beans, unground wheat. He buys cases of vinegar, tomato paste, and tea. Forty pounds of butter in one-pound cans. A hundred pounds of dried milk, sixty-five of dried fruit. Twenty-five pounds of cashews. Twenty-five pounds of oats. A forty-pound can of peanut butter. He carries it all down the Yukon from Eagle by sled or canoe. He uses a couple of moose a year, and a few bear, which are easier to handle in summer. “A moose has too much meat. The waste up here you wouldn't believe. Hunters that come through here leave a third of the moose. Indians don't waste, but with rifles they are overexcitable. They shoot into herds of caribou and wound some. I utilize everything, though. Stomach. Intestines. Head. I feed the carcasses of wolverine, marten, and fox to the dogs. Lynx is another matter. It's exceptionally good, something like chicken or pork.”

With no trouble at all, Dick Cook remembers where every trap is on his lines. He uses several hundred traps. His annual food cost is somewhere under a thousand dollars. He uses less than a hundred gallons of fuelâfor his chain saws, his small outboards, his gasoline lamps. The furs bring him a little more than his basic needsâabout fifteen hundred dollars a year. He plants a big garden. He says, “One of the points I live by is not to make any more money than is absolutely necessary.” His prospecting activity has in recent years fallen toward nil. He says he now looks for rocks not for the money but “just for the joy of itâa lot of things fall apart if you are not after money, and prospecting is one of them.”

Other books

Carrots: A Shelby Nichols Adventure by Colleen Helme

The Revolt (The Reapers: Book Two) by Katharine Sadler

The Plains of Laramie by Lauran Paine

Star Catcher by Vale, Kimber

Pulse - Part Three (The Pulse Series) by Bladon, Deborah

Henry and Ribsy by Beverly Cleary

Warrior’s Redemption by Melissa Mayhue

Identity Crisis by Melissa Schorr

THEM (Season 1): Episode 1 by Massey, M.D.