Closing the Ring (4 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

* * * * *

By June 1943, when this volume opens, the prospect in the Pacific was encouraging. The last Japanese thrusts had been hurled back and the enemy was now everywhere on the defensive. The Japanese were compelled to reinforce by costly processes the positions they still held in New Guinea, especially the garrisons of Salamaua and Lae, and to build a series of supporting airfields along the coast. The American movement towards the Philippines began to be defined. General MacArthur was working westward along the north coast of New Guinea, and Admiral Halsey was slowly advancing along the island chain of the Solomons towards Rabaul. Behind all towered up the now rapidly rising strength of the United States. The eighteen months which had passed since Pearl Harbour had revealed to the rulers of Japan some of the facts and proportions they had ignored.

1

S. E. Morison,

The Struggle for Guadalcanal.

2

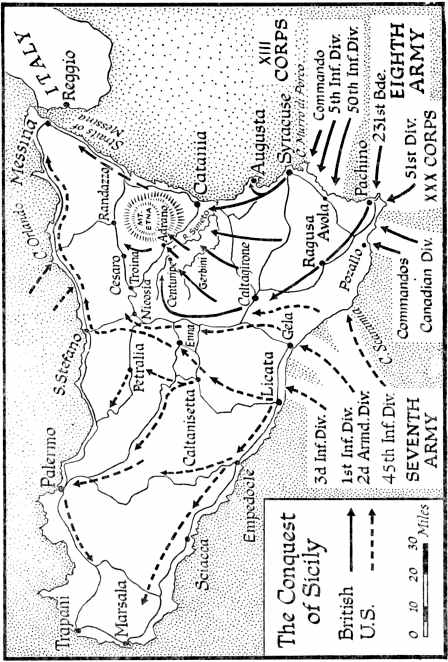

The Conquest of Sicily

July and August 1943

Preparations for Invading Sicily___General Alexander’s Final Plan___Order of Battle___Concentration of Widespread Forces___Hitler’s Conference of May

20___

Our Seizure of Pantelleria Island___Successful Cover Plans___The Appointed Day, July

10___

An Ugly Turn of the Weather___Serious Air Losses___Successful Seaborne Landings___Advance of the British and American Armies___Our Next Strategic Move___My Telegram to Smuts of July

16___

Progress of the Campaign___Eisenhower Declares for the Invasion of Italy___Discussions Between the British and American Chiefs of Staff___General Patton’s Fine Advance___Centuripe, Catania, and Messina___Alexander’s Report___Sicily Liberated in Thirty-Eight Days.

T

HE

C

ASABLANCA

C

ONFERENCE

in January decided to invade Sicily after the capture of Tunis. This great enterprise, known by the code-name “Husky,” presented new and formidable problems. Severe resistance had not been expected in the “Torch” landing, but now the still numerous Italian Army might fight desperately in defence of its homeland. In any event it would be stiffened by strong German ground and air forces. The Italian Fleet still possessed six effective modern battleships and might join in the battle.

General Eisenhower considered that Sicily should be attacked only if our purpose was to clear the Mediterranean sea-route. If our real purpose was to invade and defeat Italy, he thought that our proper initial objectives were Sardinia and Corsica, “since these islands lie on the flank of the long Italian boot and would force a very much greater dispersion of enemy strength in Italy than the mere occupation of Sicily, which lies off the mountainous toe of the peninsula.”

1

This was no doubt a military opinion of high authority, though one I could not share. But political forces play their part, and the capture of Sicily and the direct invasion of Italy were to bring about results of a far more swift and far-reaching character.

The capture of Sicily was an undertaking of the first magnitude. Although eclipsed by events in Normandy, its importance and its difficulties should not be underrated. The landing was based on the experience gained in “Torch,” and those who planned “Overlord” learned much from “Husky.” In the initial assault nearly 3000 ships and landing-craft took part, carrying between them 160,000 men, 14,000 vehicles, 600 tanks, and 1800 guns. These forces had to be collected, trained, equipped, and eventually embarked, with all the vast impedimenta of amphibious warfare, at widely dispersed bases in the Mediterranean, in Great Britain, and in the United States. Detailed planning was required from subordinate commanders whose headquarters were separated by thousands of miles. All these plans had to be welded together by the Supreme Commander at Algiers. Here a special Allied Staff controlled and co-ordinated all preparations. As the plan developed, many problems arose which could only be solved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Finally, the convoys had to be assembled, escorted across the oceans and through the narrow seas, and concentrated in the battle area at the right time.

* * * * *

Planning at General Eisenhower’s Headquarters had begun in February. It now became necessary to appoint his principal subordinates.

In all wars where allies are fighting together the control of strategy usually rests in the main with whoever holds the larger forces. This may be modified by political considerations or the relative war effort in other theatres, but the principle that the more powerful army must rule is sound. For reasons of policy we had hitherto yielded the command and direction of the campaign in Northwest Africa to the United States. At the beginning they were preponderant in numbers and influence. In the ten months that had passed since “Torch” began, the arrival of the victorious Eighth Army from the Desert and the building-up in Tunisia of the British First Army had given us the proportion there of eleven British divisions to four American. Nevertheless, I strictly adhered to the theme that “Torch” was an American expedition, and in every way supported General Eisenhower’s position as Supreme Commander. It was however understood in practice that General Alexander as Eisenhower’s Deputy had the full operational command. It was in those circumstances that the victory of Tunis was gained and the general picture presented to the American public and to the world as an overriding United States enterprise.

But now we had entered upon a new stage—the invasion of Sicily, and what should follow from it. It was agreed that action against Italy should be decided in the light of the fighting in Sicily. As the Americans became more attracted to this larger adventure, instead of being content for the rest of the year with Sardinia, and while the prospects of another joint campaign unfolded, I felt it necessary that the British should at least be equal partners with our Allies. The proportions of the armies available in July were: British, eight divisions; United States, six. Air, the United States 55 per cent; British, 45. Naval, 80 per cent British. Besides all this there remained the considerable British armies in the Middle East and in the Eastern Mediterranean, including Libya, which were independently commanded by General Maitland Wilson, from the British Headquarters at Cairo. It did not seem too much in these circumstances that we should have at least an equal share of the High Command. And this was willingly conceded by our loyal comrades. We were moreover given the direct conduct of the fighting. Alexander was to command the Fifteenth Army Group, consisting of the Seventh United States and the

Eighth British Armies. Air Chief Marshal Tedder commanded the Allied Air Force, and Admiral Cunningham the Allied naval forces. The whole was under the over-all command of General Eisenhower.

The British assault was entrusted to General Montgomery and his Eighth Army, while General Patton was nominated to command the United States Seventh Army. The naval collaborators were Admiral Ramsay, who had planned the British landings in “Torch,” and Admiral Hewitt, U.S.N., who with General Patton had carried out the Casablanca landing. In the air the chief commanders under Air Chief Marshal Tedder were General Spaatz, United States Army Air Force, and Air Marshal Coningham, while the air operations in conjunction with the Eighth Army were in the hands of Air Vice-Marshal Broadhurst, who had recently added to the fame of the Western Desert Air Force.

The plan and the troops were at first considered only on a tentative basis, as the fighting in Tunisia was still absorbing the attention of commanders and staffs, and it was not until April that we could tell what troops would be fit to take part. The major need was the early capture of ports and airfields to maintain the armies after the landings. Palermo, Catania, and Syracuse were suitable, but Messina, the best port of all, was beyond our reach. There were three main groups of airfields at the southeast corner of the island, in the Catania plain, and in the western portion of the island.

2

Air Chief Marshal Tedder argued that we must narrow the attack, capture the southeastern group of airfields, and seize Catania and Palermo later on. This meant that for some time only the small ports of Syracuse, Augusta, and Licata were likely to be available, and the armies would have to be supplied over the open beaches. This was successful, largely because of the new amphibious load-carrier, the American “D.U.K.W.,” and even more the “landing-ship tank” (L.S.T.). This type of vessel had first been conceived and developed in Britain in 1940. A new design, based on British experience, was thereafter built in large numbers in the United States and was first used in Sicily. It became the foundation of all our future amphibious operations and was often their limiting factor.

* * * * *

General Alexander’s final plan prescribed a week’s preliminary bombardment to neutralise the enemy’s navy and air. The British Eighth Army, under General Montgomery, was to assault between Cape Murro di Porco and Pozzallo and capture Syracuse and the Pachino airfield. Having established a firm bridgehead and gained touch with the United States forces on its left, it was to thrust northward to Augusta, Catania, and the Gerbini airfields. The United States Seventh Army, under General Patton, was to land between Cape Scaramia and Licata, and to capture the latter port and a group of airfields north and east of Gela. It was to protect the flank of the Eighth Army at Ragusa in its forward drive. Strong British and United States airborne troops were to be dropped by parachute or landed by glider beyond the beachheads to seize key points and aid the landings.

The Eighth Army comprised seven divisions, with an infantry brigade from the Malta garrison, two armoured brigades, and Commandos. The United States Seventh Army had six divisions under its command.

3

The enemy garrison in Sicily, at first under an Italian general, consisted of two German divisions, one of them armoured, four Italian infantry divisions, and six Italian coast-defence divisions of low quality. The German divisions were split up into battle groups, to

stiffen their allies and to counter-attack. Misreading our intentions, the enemy held the western end of the island in considerable strength. In the air our superiority was marked. Against more than 4000 operational aircraft (121 British and 146 United States squadrons) the enemy could muster in Sicily, Sardinia, Italy, and Southern France only 1850 machines.

Provided therefore that there were no mishaps in assembling and landing the troops, the prospects seemed good. The naval and military forces were however widely dispersed. The 1st Canadian Division came direct from Britain and one American division from the United States, staging only at Oran. The forces already in the Mediterranean were spread throughout North Africa. General Dempsey’s XIIIth Corps was training partly in Egypt and partly in Syria, and their ships and landing-craft would have to load not only in the Canal area and Alexandria, but at various small ports between Beirut and Tripoli. General Leese’s XXXth Corps, composed of the 1st Canadian Division in England, the 51st Division in Tunisia, and the independent 231st Brigade from Malta, would concentrate for the first time on the battlefield. American troops were similarly spread throughout Tunisia, Algeria, and beyond the Atlantic.

Subordinate commanders and Staff officers had to cover great distances by air to keep in touch with developments in the plan and to supervise the training of their units. Their frequent absence on such missions added to the burdens of the planners. Training exercises afloat were mounted in the United Kingdom and throughout the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. In the Middle East vital craft and equipment had as yet arrived only in token quantities, or not at all. All this material had in the preparatory stages to be taken on trust and included in the plan without trial. In the event nearly all the promises of the supply departments were fulfilled. In spite of many anxieties the plan went forward smoothly, and proved a remarkable example of joint Staff work.

* * * * *

On May 20, Hitler held a conference at which Keitel, Rommel, Neurath, the Foreign Secretary, and several others were present. The American translations of the secret records of this and other German conferences are taken from the manuscript in the University of Pennsylvania Library, annotated by Mr. Felix Gilbert. They are a valuable contribution to the story of the war.

Hitler:

You were in Sicily?

Neurath:

Yes, my Fuehrer, I was down there, and I spoke to General Roatta [Commander of the Italian Sixth Army in Sicily]. Among other things he told me that he did not have too much confidence in the defence of Sicily. He claimed that he is too weak, and that his troops are not properly equipped. Above all, he has only one motorised division; the rest are immobile. Every day the English do their best to shoot up the locomotives of the Sicilian railroads, for they know very well that it is almost impossible to bring up material to replace or repair them, or not possible at all. The impression I gained on the crossing from Giovanni to Messina was that almost all traffic on this short stretch is at a virtual standstill. Of the ferries there—I think there were six—only one remains. This one was being treated as a museum piece; it was said that it was being saved for better purposes.