Closing the Ring (36 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

In all these land operations the armies had been fully supported by our Tactical Air Forces, while our Strategical Air Force had carried out a number of useful raids behind the enemy lines, notably on Turin, where an important ball-bearing plant was destroyed by American Fortresses. The German Air Force, on the other hand, put forth relatively little effort. By day fighter and fighter-bomber sorties were few. Half a dozen raids by their long-range heavy bombers on Naples had little effect, but a very damaging surprise attack on our crowded harbour of Bari on December 2 blew up an ammunition ship with a chance hit and caused the sinking of sixteen other ships and the loss of thirty thousand tons of cargo.

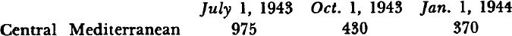

The Germans hardly troubled to contest the mastery of the air that winter over Italy, and greatly reduced their air strength, as the following table shows:

G

ERMAN

A

IR

F

ORCE

S

TRENGTHS

Our growing air offensive from England made the enemy withdraw all that could be spared from the Mediterranean and Russia. Every long-range bomber in Italy was taken away for “reprisals” against England, the “Little Blitz” of the following spring.

For reasons which have been explained, I had called the Italian campaign the Third Front. It had attracted to itself twenty good German divisions. If the garrisons kept in the Balkans for fear of attack there are added, nearly forty divisions were retained facing the Allies in the Mediterranean. Our Second Front, Northwest Europe, had not yet flared into battle, but its existence was real. About thirty enemy divisions was the least number ever opposite it, and this rose to sixty as the invasion loomed closer. Our strategic bombing from Britain forced the enemy to divert great numbers of men and masses of material to defend their homeland. These were not negligible contributions to the Russians on what they had every right to call the First Front.

* * * * *

I must end this chapter with a summary.

In this period in the war all the great strategic combinations of the Western Powers were restricted and distorted by the shortage of tank landing-craft for the transport, not so much of tanks, but of vehicles of all kinds. The letters “L.S.T.” (Landing Ship, Tanks) are burnt in upon the minds of all those who dealt with military affairs in this period. We had invaded Italy in strong force. We had an army there which, if not supported, might be entirely cast away, giving Hitler the greatest triumph he had had since the fall of France. On the other hand, there could be no question of our not making the “Overlord” attack in 1944. The utmost I asked for was an easement, if necessary, of two months—i.e., from some time in May 1944 to some time in July. This would meet the problem of the landing-craft. Instead of their having to return to England in the late autumn of 1943 before the winter gales, they could go in the early spring of 1944. If however the May date were insisted upon pedantically, and interpreted as May 1, the peril to the Allied Army in Italy seemed beyond remedy. If some of the landing-craft earmarked for “Overlord” were allowed to stay in the Mediterranean over the winter, there would be no difficulty in making a success of the Italian campaign. There were masses of troops standing idle in Africa: three or four French divisions, two or three American divisions, at least four (including the Poles) British or British-controlled divisions, were ready for action. The one thing that stood between these and effective operation in Italy was the L.S.T.s, and the main thing that stood between us and the L.S.T.s was the insistence upon an early date for their return to Britain.

The reader of the telegrams printed in this chapter must not be misled by a chance phrase here and there into thinking (

a

) that I wanted to abandon “Overlord”; (

b

) that I wanted to deprive “Overlord” of vital forces; or (

c

) that I contemplated a campaign by armies operating in the Balkan peninsula. These are legends. Never had such a wish entered my mind. Give me the easement of six weeks or two months from May 1 in the date of “Overlord” and I could for several months use the landing-craft in the Mediterranean in order to bring really effective forces to bear in Italy, and thus not only take Rome, but draw off German divisions from either or both the Russian and Normandy fronts. All these matters had been discussed in Washington without regard to the limited character of the issues with which my argument was concerned.

As we shall see presently, in the end everything that I asked for was done. The landing-craft not only were made available for upkeep in the Mediterranean; they were even allowed a further latitude for the sake of the Anzio operation in January. This in no way prevented the successful launching of “Overlord” on June 6 with adequate forces. What happened however was that the long fight about trying to get these small easements and to prevent the wholesale scrapping of one vast front in order to conform to a rigid date upon the other led to prolonged, unsatisfactory operations in Italy. Months were wasted, with grievous outflow in blood and resources, and in the end, though too late. I was actually given more than I asked.

15

Arctic Convoys Again

Suspension of the Convoys in March

1943___

Intense Struggle on the Eastern Front___The Soviet Summer Offensive___Battles of Kursk, Orel, and Kharkov___Retreat of the German Armies from Moscow to the Black Sea___Kiev Regained, November

6___

Molotov’s Request of September

21___

I Press the Admiralty to Comply___Disablement of the “Tirpitz”___Hard Treatment of Our Personnel in North Russia___My Telegram to Stalin of October

1___

A List of Modest Requests___Mr. Eden Leaves for Moscow___Stalin’s Answer of October

13___

I Report Its Character to Mr. Eden and President Roosevelt___I Refuse to Receive Stalin’s Message from the Soviet Ambassador___Mr. Eden’s Account of His Discussion with Stalin and Molotov on October

21___

The Convoys Are Resumed___The “Scharnhorst” Sunk by Admiral Fraser in the “Duke of York,” December

25, 1943___

Final Fate of the “Tirpitz,” November

12, 1944.

T

HE YEAR

1942 had closed in Arctic waters with the spirited action by British destroyers escorting a convoy to North Russia. As recorded in a previous volume, this had led to a crisis in the German High Command and the dismissal of Admiral Raeder from control of naval affairs. Between January and March, in the remaining months of almost perpetual darkness, two more convoys, of forty-two ships and six ships sailing independently, set out on this hazardous voyage. Forty arrived. During the same period thirty-six ships were safely brought back from Russian ports and five were lost. The return of daylight made it easier for the enemy to attack the convoys. What was left of the German Fleet, including the

Tirpitz

, was now concentrated in Norwegian waters, and presented a formidable and continuing threat along a large part of the route. Furthermore, the Atlantic, as always, remained the decisive theatre in the war at sea, and in March 1943 the battle with the U-boats was moving to a violent crisis. The strain on our destroyers was more than we could bear. The March convoy had to be postponed, and in April the Admiralty proposed, and I agreed, that supplies to Russia by this route should be suspended till the autumn darkness.

* * * * *

This decision was taken with deep regret because of the tremendous battles on the Russian Front which distinguished the campaign of 1943. After the spring thaw both sides gathered themselves for a momentous struggle. The Russians, both on land and in the air, had now the upper hand, and the Germans can have had few hopes of ultimate victory. Nevertheless, they got their blow in first. The Russian salient at Kursk projected dangerously into the German Front, and it was decided to pinch it out by simultaneous attacks from north and south.

1

This was foreseen by the Russians, who had had full warning and were ready. In consequence, when the attack started on July 5 the Germans met an enemy strongly installed in well-prepared defences. The northern attack made some ground, but at the end of a fortnight it had been thrown back. In the south success at first was greater and the Germans bit fifteen miles into the Russian lines. Then major counter-attacks began, and by July 23 the Russian line was fully restored. The German offensive had completely failed. They gained no advantages to make up for their heavy losses, and the new “Tiger” tanks, on which they had counted for success, had been mauled by the Russian artillery.

The German Army had already been depleted by its previous campaigns in Russia and diluted by inclusion of its second-rate allies. A great part of its strength had been massed against

Kursk at the expense of other sectors of the thousand-mile active front. Now, when the Russian blows began to fall, it was unable to parry them. While the Kursk battle was still raging and the German reserves had been deeply committed, the first blow came on July 12 against the German salient around Orel. After intense artillery preparation the main Russian attack fell on the northern face of the salient, with subsidiary onslaughts in the east. Deep penetrations were soon made, and although the defenders fought stoutly their strong-points were in succession outflanked, surrounded, and reduced. Their counter-attacks were repulsed, and under the weight of superior numbers and material they were overborne. Orel fell on August 5, and by the 18th the whole salient to a depth of fifty miles had been cut out.

The second major Russian offensive opened on August 3, while the Orel attack was still at its height. This time it was the German salient around Kharkov that suffered. Kharkov was an important centre of communications, and barred the way to the Ukraine and the Donetz industrial basin. Its defences had been prepared with more than usual thoroughness. Again the major attacks fell on the northern face of the salient, one being directed due south against Kharkov itself, another thrusting southwestward so as to threaten the whole German rear. Within forty-eight hours both of these had bitten deep, in places up to thirty miles, and Bielgorod had been taken. By August 11, Kharkov was threatened on three sides, a further attack from the east having been launched, while fifty miles to the northwest the Russians were advancing fast. On that day Hitler ordered that Kharkov was to be held at all costs. The German garrison stood to fight it out, and it was not till the 23d that the whole town was in Russian hands.

These three immense battles of Kursk, Orel, and Kharkov all within a space of two months, marked the ruin of the German army on the Eastern Front. Everywhere they had been outfought and overwhelmed. The Russian plan, vast though it was, never outran their resources. It was not only on land that the Russians proved their new superiority. In

the air about twenty-five hundred German aircraft were opposed by at least twice as many Russian planes, whose efficiency had been much improved. The German Air Force at this period of the war was at the peak of its strength, numbering about six thousand aircraft in all. That less than half could be spared to support this crucial campaign is proof enough of the value to Russia of our operations in the Mediterranean and of the growing Allied bomber effort based on Britain. In fighter aircraft especially the Germans felt the pinch. Although inferior on the Eastern Front, yet in September they had to weaken it still more in order to defend themselves in the West, where by the winter nearly three-quarters of the total German fighter strength was deployed. The swift and overlapping Russian blows gave the Germans no opportunity to make the best use of their air resources. Air units were frequently moved from one battle area to another in order to meet a fresh crisis, and wherever they went, leaving a gap behind them, they found the Russian planes in overmastering strength.

In September, the Germans were in retreat along the whole of their southern front, from opposite Moscow to the Black Sea. The Russians swung forward in full pursuit. At the northern hinge a Russian thrust from Viazma took Smolensk on September 25. No doubt the Germans hoped to stand on the Dnieper, the next great river line, but by early October the Russians were across it north of Kiev, and to the south at Pereyaslav and Kremenchug. Farther south again Dniepropetrovsk was taken on October 25. Only near the mouth of the river were the Germans still on the western bank of the Dnieper; all the rest had gone. The land approach to the Crimea, at Perekop, was captured by the Red Army, and the retreat of the strong German garrison in the Crimea was cut off. Kiev, outflanked on either side, fell on November 6, with many prisoners, and the Russians, driving forward, reached Korosten and Jitomir. But a strong armoured counter-attack on their flank drove them back, and the Germans recaptured the two towns. Here the front stabilised for the time being.

In the north, Gomel was taken at the end of November, and the upper reaches of the Dnieper crossed on each side of Mogilev.