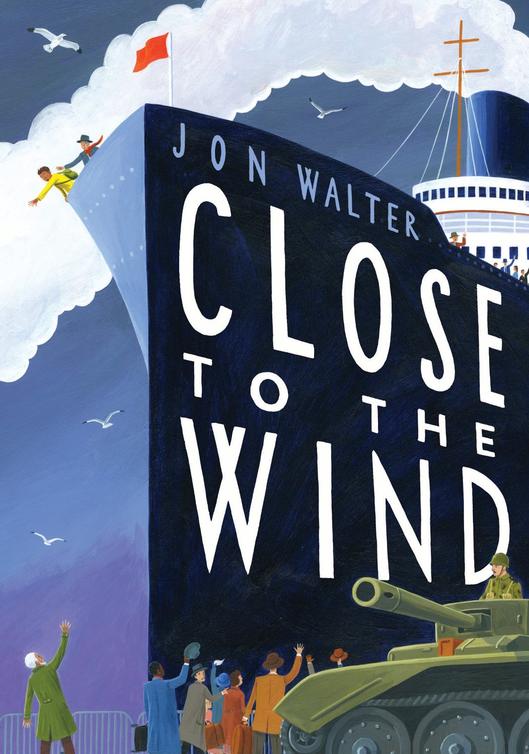

Close to the Wind

Authors: Jon Walter

To my wife Tanya – for everything

T

he boy and the old man arrived at the port at night.

There had been cloud in the sky but now the moon shone brightly and they stood in the shadow cast by a row of terraced cottages that lined a cobbled street, polished through the years by wheels and feet and the hooves of horses.

The boy held the old man’s hand.

The air smelled of motor oil and charred timber. At the far end of the street, the quayside was lit by a bright white lamp that glared upon the skeleton of a single black crane, its hook hanging solemn above the cottage roofs, and above the crane loomed the tall ship, a string of yellow bulbs along the rails of its upper decks as though it might be Christmas and not a warm autumn night.

The boy sneezed loudly.

‘Shhh, Malik,’ hissed his grandfather.

Malik let go of his grandfather’s hand and pinched his nose through the white cotton

handkerchief

that covered his face – his grandfather had tied it across his nose and mouth to protect him from smoke. Malik could have removed the cloth, since they were a long way from the fires, but he kept it, believing it made him look older. He held his breath

so that he wouldn’t sneeze again. When he was certain, he took his hand away. ‘Sorry, Papa.’

Papa settled a hand on Malik’s shoulder. ‘No. I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to bite.’ He glanced back down the road behind them. ‘I’m still nervous. I’m sure there’s no one here, but we ought to be careful.’

‘Careful as a cat,’ said Malik.

‘Fearful like a fox,’ said Papa, and he adjusted the rucksack that he carried slung from a single shoulder.

Malik nodded. He felt sorry for the foxes – nobody ever had a good word to say about them. He saw Papa’s eyes flick to either end of the street and his stomach tensed as though he were about to be punched. These moments of uncertainty were the worst. He put a hand to the front of his trousers and held himself.

Papa looked down at him. ‘Do you need the toilet?’ Malik shook his head. ‘Then don’t do that, eh? You’re too old for that.’

Malik put his hand in his trouser pocket. He shuffled on his feet, stepping from one side to the other so that the tops of his green Wellington boots flapped against his trousers. Papa’s eyes went up and down the row of cottages; he was checking for something.

Malik stopped shuffling and lifted himself on tiptoes so as to be closer to Papa’s ear. ‘Is that our ship?’

Papa pulled the collar of his thick winter coat away from the back of his neck. His brow was damp with sweat. ‘I expect it is,’ he said quietly. ‘I can’t see the name, but it’s the only ship here.’

Malik looked again and he agreed. There were no other ships.

Papa put a hand to his short, white beard and tugged at the hair, something he did when he was thinking. ‘We’re too early. We can’t go there yet. I think we must wait till the morning.’

The muscles in Malik’s stomach twisted – Papa would need to find them a place to stay again. Last night they had slept in the basement cellar of a burnt-out office block and there had been a dying dog. He followed Papa’s eyes to the row of cottages, silhouetted in the bright light from the quay, the chimneys standing proud of the grey slate roofs. If they couldn’t go to the ship, then perhaps they could spend the night in one of these. Malik hoped so. He imagined a chair to sit in. A basin for washing. His own bed.

‘Will the ship leave tomorrow?’

Papa ignored the question and Malik felt guilty

for having asked it, but he had other questions, all sorts of questions, and he couldn’t help himself.

‘Is this where we’re staying?’ he asked. ‘Is this where Mama will meet us?’

Papa raised his voice. ‘So many questions. I’ve told you about that. How many questions is that you’ve asked today?’

Malik dropped his head. ‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t know? Well, I don’t know either. There’s been so many I’ve lost count. But we agreed on ten, didn’t we? We had an agreement and we shook hands on it. Only ten questions each day.’ Papa took a deep breath and lowered his voice. ‘I reckon you’ve got just one left and that’s being generous. You should be careful – think about what you say before you open your mouth.’

Malik tightened his jaw. Papa never liked too many questions: he had learned that in the last two days. He stepped again from one foot to the other, thinking of what he could get away with saying next. A question mark hung over everything. ‘How do you … I mean … what should I …?’ He reached for Papa’s hand, gripped his index finger. ‘It’s impossible.’

‘No. It’s not impossible. It’s difficult, I’ll grant you

that.’ Papa squeezed Malik’s fingers then knelt beside him and pointed. ‘See that cottage there? The one with the dark red door?’

Malik was disappointed. ‘The one with the broken window?’

‘Yes. That’s the one. I want you to count the houses from this end of the street till you get to the one with the broken window. Tell me how many houses there are before you reach the one we want.’

This was one of Papa’s games. Malik knew them now, the little things Papa gave him to do to keep his mind occupied. It was what Mama used to do when he was young but Malik didn’t mind Papa doing it now. It was better than having too much time to think.

He began to count under his breath, nodding his head at each house. ‘Thirteen,’ he said.

‘Are you sure?’ Papa narrowed his eyes. ‘I made it twelve. Let’s do it together.’

They began to count and Papa pointed at each cottage in turn. Malik took hold of his hand to stop him after seven. ‘No, Papa. Look. That one’s different. That’s two houses. There’s another front door. See? A shared porch with two front doors.’

Papa’s eyes flicked to the walls either side of the

porch. He checked the windows. ‘Yes, I see. You’re right. One porch but with two front doors. Two eyes are better than one, eh?’ He touched the top of Malik’s head. ‘We make a good team.’

Malik’s mouth whipped up into a smile. ‘Who lives there? How do we know them? Are they friends of ours?’

Papa didn’t seem to mind the questions. He checked the street again to make sure they were safe. ‘I hope no one lives there. They should have left when the trouble started. I don’t think anyone still lives in these streets.’

A cloud moved across the moon and the cobbles on the street turned black. An engine started up from somewhere in the distance, probably from the quayside.

Papa took hold of Malik’s hand. ‘I think we should go.’

‘Is it soldiers?’

‘I don’t think so. But we’ve been here too long. We should be out of sight. Come on.’

Papa stepped out across the street and Malik ran to keep up, his head ducked low to avoid the

rucksack

which bounced from side to side on Papa’s back. They hurried to the opposite pavement, rounded the

final cottage and slipped into the alley that divided the back of the houses in this street from the next.

Papa stopped running and drew Malik close to him by the hand. ‘It’s very dark, isn’t it? Now the moon has gone, I can’t see my own feet.’

Malik looked for his own feet and saw nothing but black. He held a hand up to his face, moved it toward his nose and away again.

‘We’ll go slowly,’ Papa whispered. ‘Count the houses for me, will you? We want number thirteen.’

‘I can’t see the houses, Papa. It’s too dark.’

Papa put an arm round Malik’s shoulder. ‘You’re right. It’s too dark to see the houses.’ He lifted Malik’s hand and his fingers brushed against brickwork. ‘Feel that, Malik? That’s the back wall to the yard of the first house. We can count the gates till we reach thirteen.’

They walked into the darkness, holding hands. ‘It’s too dark,’ Malik complained. ‘I don’t like the dark.’

‘No,’ agreed Papa. ‘Nobody likes the dark. But you should remember that there’s no one here and the dark can’t hurt us.’

Malik knew that Papa couldn’t really know that for certain – you can never know for sure if

there’s anything in the dark. ‘Can we use the torch?’

‘No. We don’t need the torch.’

‘I do.’

‘No, you don’t. Feel with your fingers.’

‘It would be better with the torch.’

‘Malik! We can’t use the torch. They could see the torch.’ Papa caught his breath and stopped walking.

Malik came up close against him. He tried to see Papa’s face. ‘You said there were no soldiers. You told me it was only us. If there’s no one here then no one can see the light.’

‘Yes.’ Papa sighed. ‘I suppose you’re right.’ He took the rucksack from his back and placed it on the floor. ‘You’re using logic and I can’t argue with that. I suppose we don’t need to whisper either.’

‘The torch is in the top pocket, Papa. The one on top of the flap that goes over.’

‘Yes. Thank you. I remember.’ Papa slid back the zip and took out the thin metal torch, twisting the bulb casing till the light came on and turned the edge of his fingers pink.

‘Can I hold it?’

Papa put the torch into Malik’s hand and directed it down to the floor. ‘Keep it pointed at the ground.

Just down near your feet.’ The thin beam picked out the green rubber of Malik’s Wellington boots. ‘Your feet must be hot in those boots. You’ll be able to take them off soon.’

‘I don’t mind.’ Malik nudged the torch beam ahead of his feet and the shaft of light showed a little yellow flower, sprouting up between the broken stones that paved the alley. ‘Look. I nearly trod on a flower.’

‘It’s a weed, Malik. A dandelion.’

Malik stooped and broke the stem of the yellow flower. ‘It’s for Mama,’ he said. ‘I’m going to save it for her.’

They went on through the darkness, but quicker now they had some light. They counted the gates as they passed. The torch picked out one that was painted red and another that was green. At the thirteenth gate, an upturned metal bin lay on the ground with rubbish spilling from the open top. Something smelled rotten. The torch showed them an open can lying on its side, used teabags and half a

cauliflower

that was almost black. Malik stepped on a soiled newspaper. Above him the clouds thinned enough to give them a little light. This was the thirteenth house.

‘Is this it?’ Malik’s breath moved the handkerchief on his face. He flicked the torch up to Papa’s face and saw him turn and scowl.

‘Yes, this is it. Put the torch out now, will you? The moon will give us enough light.’

Malik turned off the torch and they paused. Papa put his hand into the pocket of his coat and Malik knew that in Papa’s pocket there were two red apples and the knife with the blade that folded back into the curved wooden handle. He had seen Papa reach into his pocket and touch it before, always when he needed courage. Malik wanted a knife just like that.

Papa took two steps to the gate, twisted the metal latch and opened it. The moonlight showed them the back of the cottage through the open gate. Malik could see a back door with pretty glass squares, and to the right of it a window. It looked like a nice house. Small, but comfortable.

Papa tugged at his beard. ‘You better stay here.’

‘Why? I don’t want to.’

‘It’s better for you to wait while I check to see that it’s all right.’

‘To see if there’s a dead dog?’

‘No. Not to see if there’s a dead dog. There won’t be another dead dog, Malik.’

‘How do you know?’

Papa put a hand to his head and closed his eyes. ‘No. No, that’s too many questions. You’re doing it again.’ He held out his hand and sliced the air into sections as he spoke. ‘I don’t know for certain. Of course I don’t. But it’s unlikely. It’s very unlikely. It would be unfortunate to find another dead dog.’

Malik gripped the little yellow flower in his hand and remembered the dead dog on the cellar floor, down by the metal grille. It hadn’t been dead at first but it was now. It was probably still on its own, lying where they had left it.

‘Please, Papa. I don’t want to wait here on my own.’ Malik tried not to whine, and hoped Papa wouldn’t be angry.

Papa nodded. ‘OK.’ He took hold of Malik’s hand. ‘Let’s go together.’

They stepped across the yard and found the back door locked. Papa went to the window, put his face against the glass, then came back to Malik. ‘I need the handkerchief from your face.’ He reached around, undid the knot at the back of Malik’s head, then wrapped his hand in the cloth and punched through one of the small panes, just above the doorknob. The sound of breaking glass shattered the silence. Malik

held his breath, half expecting a shout or a rush of feet, but nothing happened.

Papa unwound the handkerchief from his fingers. He had a single small cut on the middle knuckle and he put it to his mouth, sucked away the blood, then reached inside and turned the key that was in the lock. The hinges of the door creaked as he opened it and stepped inside. He looked back at Malik. ‘You’d better turn the torch on.’

Malik twisted the top of the torch and followed Papa. The beam picked out wallpaper the colour of cornflowers, and that looked very pretty, but it was only the top half of the wall. The bottom half had bare plaster with corrugated ridges of brown glue where the kitchen units had been pulled away. Two pipes ran along the skirting board and had been capped off with a simple tap where there had once been a sink. On the floor, below the tap, stood a yellow plastic bucket full of discarded drink cans. Malik trod on screws and broken bits of masonry as he turned the torch around the empty room. He should have known it would be like this.

‘It might be better through here.’ Papa stepped onto the bare floorboards of the dark hall. ‘Come on, hand me the torch.’

They crept along the passage till the beam picked out a door. Papa pushed it open and stepped inside the hollow room. There was no furniture and no carpet. A ragged hole in the brickwork of the opposite wall showed where the fireplace had once been, and no curtain hung across the broken glass of the window. There was no comfort to be found here. None at all.

‘There’s nothing here, Papa.’

‘No, Malik. I can see. People have been here. They’ve stripped the house bare. Everything that was worth anything has gone. You can be certain of that.’

Malik walked over to the window and looked out across the empty street. This was only just better than the cellar. Mama wouldn’t like this house at all, and she wouldn’t want to come here.