Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (31 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

5. The Early Church in the Middle East

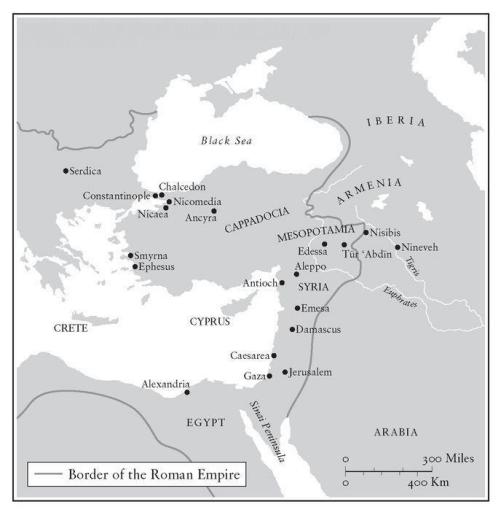

The Holy Land in which Christianity emerged represents the southern-most end of a Semitic cultural zone stretching more than seven hundred miles from the desert of Sinai on the borders of Egypt up to the Taurus Mountains, which shield the plateaux of Armenia. In its northern region, it is crossed by the two great rivers Tigris and Euphrates, which flow down to the south-east, giving fertility and prosperity to Mesopotamia ('the land between the rivers') and into the Persian Gulf. The Romans gave the name 'Syria' to the whole region, Palestine included; today it is politically divided between Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, northern Iraq and eastern Turkey, and its present state of tension is nothing new. It has always been the area's economic fortune and political misfortune to look both west across the Mediterranean and east to Central Asia and down the two rivers. In terms of trade and transport it is a fulcrum for sea routes west, land routes to the south into Africa and the beginning of trails eastward through the Asian steppes, then already established over centuries as the 'Silk Road' to China. Politically, the Tigris and Euphrates formed a much-contested boundary for a historic series of opposed great powers and cultures - in the time of the early Christians, westwards was the Roman Empire, eastwards the Parthians and later the Sassanian Persians.

Even at the height of Roman success in spreading its power beyond the Euphrates in the second century CE, much of the Syrian region was only very superficially part of the Graeco-Roman world. Beyond the dignified Classical architecture of government buildings and the polite-ness of Hellenized city elites who did their best to ape the glory days of Athens, Latin and Greek would fade from the ear and the babble of voices in the street was dominated by some variant of the language which Jesus had spoken: Aramaic. Languages like it became known as Syriac and there was originally a single alphabetic script for its literature: Estrangela. Eventually, after the fifth century, the turmoil of war and Christian controversy (see pp. 220-40) made the Euphrates a fairly fixed border for centuries. That heightened the sense of difference between east and west Syria either side of the river. As a consequence there developed two ways of reading the Syriac language, written in divergent scripts derived from Estrangela: Serto in the west, Nestorian in the east.

48

It was not surprising that Syriac Christians continued to have intimate ties with Judaism. The region provided the natural routes for Jews who wanted to travel to Jerusalem from Mesopotamia in the Parthian and Sassanian empires, where Babylon continued to sustain the large and cultured Jewish community which had arrived at the time of the Exile (see pp. 61-3). The rulers of one small kingdom to the east of the River Tigris, Adiabene (in the region of the modern Iraqi city of Arbil), were actually converted to Judaism by Jewish merchants in the first century and gave active assistance to the rebels in the Jewish revolt of 66-70 CE.

49

With such encouragement, there was a lively Jewish presence throughout the region, so Christianity arrived early. Following the precedent of the

Didache

, which was compiled somewhere in the Syriac region (see p. 120), the liturgy of the Syriac Church continued to have a much more Jewish character than elsewhere.

50

There was soon a Bible in Syriac, whose developed form in the fifth century was called the

Peshitta

, a word meaning 'simple' or 'current' (rather as the developed Latin Bible of the fourth century was called 'common' or 'Vulgate'), the Syriac Old Testament part of which may have been independently created by Syriac-speaking Jews.

51

A small Hellenistic Syrian city called Dura Europos on the banks of the Euphrates was destroyed by the Sassanians around 256-7 after a century of Roman military occupation.

52

Abandoned for ever, it proved a sensationally well-preserved paradise for twentieth-century archaeologists. Its unfortunate inhabitants are unlikely to feel much posthumous compensation for their disaster in the current fame of their city, which centres on the twin revelation of the world's oldest known surviving synagogue and oldest known surviving Christian church building, both preserved when buried in earth defences in the final siege, some decades after their original construction. Both buildings are additionally famous for their wall paintings. The Jewish paintings, a cycle of scenes from the Tanakh, are rather finer than their Christian counterparts. Their very existence is an instructive surprise in view of the later Jewish consensus against representations of the sacred, although being paintings technically they do not violate the Second Commandment's prohibition of graven or sculptured images.

53

The Christian church at Dura had been converted from a courtyard house and in plan is therefore very unlike the churches of later Christianity anywhere in the world. Like many of the developed churches of the next few centuries, it does have separate chambers for congregational worship and for the initiation rite of baptism, together with a separate space for those who are still under instruction (the 'catechumens'), but there is one remarkable oddity, making it different from any subsequent Christian church building before some of the more radical products of the Protestant Reformation thirteen hundred years later: there is apparently no substantial architectural provision for an altar for the Eucharist.

54

The subjects of the paintings in the various rooms contrast with those of the synagogue in being derived from the New Testament, including Christ as the Good Shepherd, one of the first favourites in Christian art generally, and the three Marys about to investigate Christ's tomb after the Resurrection. Absent is the representation which modern Christians might expect, but which was nowhere to be found in Christian cultures before the fifth century: Christ hanging on the Cross, the Crucifixion. Christ in the art of the early Church was shown in his human life or sprung to new life - never dead, in the fashion of the crucifixions which were to become so universal in the art of the later Western Church.

One of the other little border kingdoms of Syria, Osrhoene, had its capital at Edessa (now Urfa in Turkey), which in fact provides the earliest record of a Christian church building, predating the existing remains at Dura Europos. We know that it was destroyed in a flood in 201.

55

The Romans conquered Osrhoene and made it part of the empire in the 240s, but before that its kings had let Christianity flourish. Later Syrian Christians celebrated this in the legend of King Abgar V of Osrhoene, who back in the first century was supposed to have received a portrait of Jesus Christ from the Saviour himself and to have corresponded with him. The fourth-century Greek historian Eusebius took a great interest in Abgar, preserving the supposed correspondence, although apparently as yet unaware of the portrait, and the elaborated legend gained an extraordinary popularity westwards far beyond Syria. Partly this was because it remedied an embarrassing deficiency in the story of early Christianity, a lack of an intimate connection with any monarchy. That was probably why Eusebius discussed Abgar, exultant chronicler as he was of the Emperor Constantine I's new alliance with the Church, and in general a writer little excited by the Church on the eastern fringe of the empire.

56

Equally, as the cult of relics gathered pace in the fourth and fifth centuries, there was sheer fascination for many devout Christians in the idea of a relic provided by Christ himself. In an elaborated version of the story, this portrait became the first of many Christian displays of a miraculous imprint of an image on cloth, which naturally possessed impressive powers as a result. Later, in 944, now known as the

Mandylion

(towel) of Edessa, the healing cloth was taken to Constantinople. Later still, taking the story even further west, it was linked to another mysterious expanse of cloth now preserved in Turin Cathedral as the shroud of Christ, despite the likelihood that this admittedly remarkable object was created in medieval Europe.

57

The most bizarre outcrop of the Abgar legend was its redeployment in the interest of medieval and Tudor monarchs far away in England. Under his Latin name Lucius, King in Britium, the Latin name for the fortress-hill looming over the city of Edessa, Abgar became by creative misunderstanding King Lucius of Britannia, welcoming early Christian missionaries to what would become England's green and pleasant land. Although the heroic error seems in the beginning to have been the fault of an author in the entourage of a sixth-century pope in Rome, the story became much beloved by early English Protestants when they were looking for an origin for the English Church which did not involve the annoying intervention of Augustine of Canterbury's mission from Pope Gregory I (see pp. 334-9), but the Abgar legend was more generally pressed into polemical service by a remarkable variety of combative clergy in the English Reformation.

58

This was a far cry from its original purpose as a self-serving story for the Syriac Church, designed to testify to its early and royal origins. That story probably reached its full elaboration at a time when Syriac bishops and local leaders were hoping to curry favour with or impress late Roman emperors in Constantinople. The legend's back-dating to the first century CE was helped by the fact that most kings from the dynasty of Osrhoene were called Abgar. If the story of the Edessan monarchs' favour to the Church has any plausible chronological setting, it was probably Abgar VIII 'the Great' (177-212), not the first-century Abgar V, who first gave Christianity an established place in Edessa at the end of the second century, following the precedent of the royal conversions to Judaism in Adiabene 150 years before.

59

But there was much more to the Church of Edessa and Syria beyond it than just the elaborated legend of a towel. Its legacy to the universal Church was many-sided, not always to the comfort of Christians to the west. At the same time as generations of bishops and scholars from Ignatius to Origen were shaping Christian belief within the imperial Catholic Church, individual voices were emerging in Syriac Christianity which frequently earned suspicion and condemnation from neighbours to the west. The first major personality of the Syriac Church for whom there is reasonably certain dating was a combative Christian convert from Mesopotamia who, in the mid-second century, travelled as far as Rome for study, and who was known in Greek and Latin as Tatian. Tatian followed Justin Martyr (who was his teacher in Rome) in writing a vigorous defence of Christianity's antiquity which won grudging praise from Catholic Christians - 'the best and most useful of all his treatises,' said Eusebius nearly two centuries later - but his independence of mind led to accusations that he was an exponent of the gnostic system of Valentinus.

60

This was probably a smear, intended to discredit him, for Tatian was responsible for another major enterprise, the harmonization (

Diatessaron

) of the four canonical Gospels. This might seem a controversial enterprise, but in the very fact that he chose the four accepted by the emerging mainstream Church, Tatian showed just how far he was from the gnostic proliferation of Gospel accounts.

Many found the

Diatessaron

useful. A parchment fragment of it has been recovered from the ruins of Dura and some version of a Gospel harmony survived long enough to be translated into Arabic and Persian perhaps five centuries later.

61

Although in the end the prestige of the four originals would overcome Tatian's synthesis of them, many Christians at the time found it difficult to see why they should use four discrepant versions of the same good news. In an era when at least one Syrian Church in the north-east corner of the Mediterranean was in any case using an entirely different Gospel from the canonical four, it made sense to try to create a single definitive version for liturgical use.

62

A consolidated Gospel message was also a weapon against Marcion's minimalist view of Christian sacred texts - given that so much of Syrian Christianity was still unusually close to its Jewish origins, Marcion's anti-Jewish views were particularly disruptive in Syria.

63

Despite Tatian's impeccably anti-Marcionist line, subsequent Christian censorship has not allowed Tatian's harmonized Gospel text or indeed most of his other writings to come down to us complete. The worst that one can say of his individuality on the evidence available was that he was enthusiastic for the sort of world-denying lifestyle which in the next century crystallized into monasticism. His second-century assertion of ascetic values is one of the signs that we should look behind the common story of monastic origins in Egypt and give the credit to Syria. Tatian's problem was that, in terms of the subsequent writing of Christian history, he was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

64

More definitely at odds with the Catholic Church developing to the west was Bar-Daisan (Bardesanes in Greek), from a generation after Tatian in the later second century. Some sources assert that, like Tatian before him, he created his own version of the Gospels (if it ever existed, it is now completely lost), and although he was another bitter opponent of Marcion, he was also accused of heresy by later authors. He certainly denied what became the mainstream Christian doctrine that the body is resurrected along with the immortal soul, and in a linked train of thought, he denied the bodily sufferings of Christ in his Crucifixion. It was small wonder that in the fourth century the much more self-consciously orthodox Syrian theologian Ephrem looked back on Bar-Daisan as 'the teacher of Mani'.

65

Yet Ephrem gave credit to his heretical predecessor in one very significant respect: he admitted to having borrowed rhythms and melodies from Bar-Daisan's hymns, adding to them new and theologically correct words, on the grounds that their beauty 'still beguiled the hearts of men'.

66