Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (24 page)

Read Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States Online

Authors: Andrew Coe

According to a

Philadelphia Inquirer

headline, the moral of this tale was “The Origin of Chop Suey Is an Enormous Chinese Joke.”

41

Even today, the dish is described as the “biggest culinary joke played by one culture on another.”

42

In every version, the butts of the joke were the Americans who were too stupid to know that they were essentially eating garbage.

In reality, of course, the Sze Yap–born residents of Chinatown apparently liked chop suey just as much as the barbarians, and there is no evidence of white San Franciscans eating chop suey before 1900. So why did the “experts” repeat a story that appears to have no basis in fact? Well, the tale about the bullying of the Chinese restaurant owner does ring true, and the punch line about eating garbage suggests a veiled revenge (analogous to the chef spitting in the soup) for decades of mistreatment. Call it a myth that conveys a larger historical “truth.” Despite these stories, the hungry American masses kept on gobbling chop suey with gusto, for now.

American Chop Suey

In 1909, Elsie Sigel, age nineteen, lived in New York City’s Washington Heights and liked Chinese food and, apparently, Chinese men. Elsie’s mother, devoting her energies to converting the Chinese to Christianity, regularly visited a mission down on Mott Street. Both mother and daughter frequented two “chop sueys”—the one in their Upper Manhattan neighborhood and a high-class Chinese restaurant down on Mott Street named the Port Arthur. The Sigels’ apartment was decorated with vases, tea sets, and other curios from Chinatown. Elsie’s father, Paul Sigel, a government clerk whose father had been a revered general in the Civil War, detested his wife’s mission work and often threatened to eject any Chinese men he found visiting the Sigel household. In fact, Chinese men often did visit; they came to ask for Mrs. Sigel’s help and to court her daughter. Though not considered a beauty—she had a broad, flat nose and bad teeth—Elsie was pleasingly plump, dressed well, and possessed an agreeable, soft-spoken nature. Attracted by these qualities, both Leon Ling, the suave and well-dressed ex-manager of the Washington Heights chop

suey, and Chu Gain, the manager of the Port Arthur, were among her suitors. Mrs. Sigel favored Chu Gain, who was rumored to be wealthy, but Elsie preferred Ling and had been writing steamy notes to him for over a year. Many guessed that she and Ling were having an affair. However, in the spring of 1909 Elsie seemed to be tiring of Ling and, swayed by her mother, turning her affections to Chu Gain. Those who knew the trio sensed that something bad might happen: Leon Ling was persistent and known to have a violent streak.

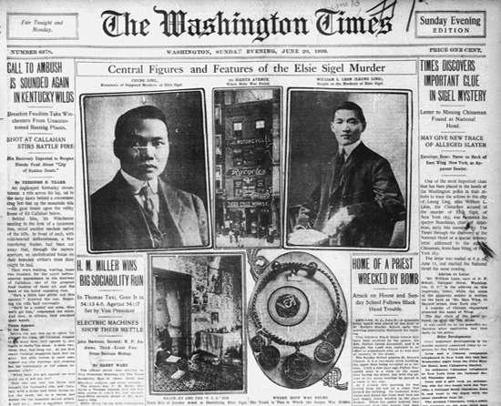

Figure 6.1. Elsie Sigel’s unsolved

1909

murder, dubbed the “Chinatown Trunk Mystery” by the national media, reinforced misgivings about the exotic world of that neighborhood. The police description of the main suspect as a “Chinaman” who “usually dresses like an American” and “talks good English” did not allay unease.

On the morning of June 9, 1909, Elsie Sigel told her mother that she was going to visit the grocer, the butcher, and then her grandmother in the Bronx. She made the first two stops but never arrived at her grandmother’s. By evening, the family was worried, their fears only partially alleviated by the arrival of a telegram from Washington, D.C.: “Don’t worry. Will be home Sunday noon. E.J.S.” Sure that her daughter had eloped, most likely with Leon Ling, they nevertheless hurried to Chinatown the next morning to see if they could locate her. (Fearing a scandal, they didn’t report the disappearance to the police.) They scoured the neighborhood between Broadway and the Bowery, running into Chu Gain, who joined the search for Elsie, but not Leon Ling. Sun Leung, the owner of a restaurant over a bicycle store at Eighth Avenue and Forty-eighth Street, was also looking for Leon Ling, who worked there as a waiter. Ling shared an apartment with two other Chinese men on the fourth floor of the restaurant’s building. Sun Leung knocked on the door of his room again and again over the next few days, until on June 18 he smelled a foul odor coming from behind the door. He ran for a policeman, who soon arrived with a locksmith to open the room. Inside the small, neat bedroom, they found a black trunk bound with rope. The policeman cut the rope, pried open the lid, and uncovered the decaying corpse of a young woman, wrapped in a blanket. Nothing in the trunk identified the body, but investigators found a letter in a bureau addressed to a “Miss Elizabeth Sigel.” They hurried to Washington Heights.

Paul Sigel admitted that his daughter was missing, but on viewing the body, neither he nor his two sons would confirm that the young woman was Elsie. Positive identification came from Mrs. Florence Todd, the head of the Mott Street mission, and two days later the Sigel family held a private funeral at the Woodlawn Cemetery. Afterward, Mrs. Sigel retired to

a sanatorium in Connecticut, and Elsie’s father and brothers refused to make any further comment about the frightful case. Throughout the city and indeed across the nation, an uproar arose about the murder. “Chinaman Is Supposed to Be the Murderer of Young Girl” blared the

Ogden Standard

out in Utah, one of the many newspapers that led with the story. In response to the outcry, the police began an intensive manhunt for Leon Ling, wiring descriptions of him around the country. They rounded up all the Chinese people associated with the case and submitted them to questioning that sometimes turned brutal. Out on the street, any Chinese man who looked “Americanized”—in Western clothes and without a queue—was viewed with suspicion. In upstate New York, Pennsylvania, Chicago, California, and elsewhere, local whites turned in dozens of Asian men, both Chinese and Japanese. Despite a watch kept at every major railroad station and the Pacific Mail steamship docks in San Francisco, the presumed murderer remained elusive. The New York police declared that they would soon get their man, but William M. Clemens, the

Chicago Tribune

’s “Famous Expert in Crimology,” thought otherwise: “The New York sleuths did not reckon with the Chinese mind. . . . A race that drinks its wine hot, shakes hands with itself in greeting, eats its eggs and melon only when old and dried—such a race in criminal things can be looked upon for unexpected cunning.”

1

Ling was never caught, and the real story of how Elsie Sigel died remains a mystery.

The case received such widespread publicity partly because “white slavery” was a prominent issue at the time. Many influential people, including politicians, policemen, religious leaders, and feminists, believed that an epidemic of prostitution was sweeping across the country and young women were being forced into lives of shame. This conviction had many roots, including the fact that thousands of women were

finding jobs and a new financial independence in cities, prejudice toward the masses of European immigrants (including many single young women) then arriving, and a few actual prostitution cases. The outcry over Elsie Sigel’s murder helped link the nation’s Chinatowns and their thousands of chop suey joints to the white slavery issue. Like public dance halls, brothels, gambling houses, and disreputable hotels, reformers declared that Chinese restaurants were places where unmarried women could be lured into depravity. On Mott Street, where the restaurants did the bulk of their business late at night, the police forced early closing times and temporarily barred unaccompanied white women from the district altogether. In her book

The Market for Souls

, Elizabeth Goodnow describes her tour of Lower Manhattan’s fleshpots, ending with Chinatown: “We entered a house that had a chop suey place on the first floor. The rest of the house was filled with women and the fumes of opium came down the stairs.”

2

Goodnow ascends to the bordello and finds a small room furnished with gaudy Chinese embroidery and a Chinese idol. On the bed lies a white prostitute who has killed herself with an overdose of opium, another victim of the path to ruin that began with an innocent visit to Chinatown. The

Chicago Tribune

reported:

More than 300 Chicago white girls have sacrificed themselves to the influence of the chop suey ‘joints’ during the last year, according to police statistics . . . . Vanity and the desire for showy clothes led to their downfall, it is declared. It was accomplished only after they smoked and drank in the chop suey restaurants and permitted themselves to be hypnotized by the dreamy, seductive music that is always on tap.

3

Meanwhile, in South Bend, Indiana, the Board of Health was more direct, calling that city’s Chinese restaurants

“nothing but opium joints with chop suey attachments.”

4

The police and other groups continued to associate chop sueys with sin for almost a decade, and news of Chinatown raids dominated headlines.

Back on the women’s page, something very different was happening. Instead of joining in the anti–Chinese food frenzy, syndicated columnists like Marion Harland and Jane Eddington published numerous recipes for chop suey and other dishes, apparently due to public demand. As Eddington wrote in 1914 in the

Chicago Tribune

, “there is always a demand for chop suey recipes.” One of the most prolific women writers of her time, Harland was always game to try new things, even at age eighty-three:

So many nationalities unite to make up the American people that it is only natural we should have diversities in our bill of fare. For myself, I like it. I enjoy trying new dishes and adding to my table combinations which have had their birth on the other side of the ocean. . . . We have gone further afield and eaten and enjoyed chop suey, and from a number of our constituency have come requests for full and minute directions for making this Chinese dish, for instructions how and with what to serve it.

5

The first Chinese cookbook for American readers,

Chinese Cookery in the Home Kitchen

, had been written two years earlier by another newspaperwoman, Jessie Louise Nolton of the

Chicago Inter-Ocean

. The recipes replicated the menu of the average downtown Chinese restaurant: boiled rice, multiple kinds of “chop sooy,” “eggs fo yong,” roast pork and chicken, fried rice, and so on.

For more sophisticated housewives, preparing a bowl of chop suey for the family meal was not enough. In 1913,

Harper’s Bazaar

published a series of articles on how to

cook and serve a Chinese dinner, luncheon, and tea party. These pieces were written by one Sara Eaton Bossé, the daughter of a Chinese mother and English father, who lived a distinctly Bohemian lifestyle as a painter and artist’s model in New York. For her, these Chinese parties were theatrical events, a way of escaping from middle-class existence into the realm of East Asian exotica: “A Chinese dinner, properly served, proves a delightful and novel form of entertainment. It should be served, of course, in the purely Chinese fashion, which lends an added charm and mystery to the dishes themselves.”

6

Preparation for these parties took days, beginning with trips to Chinatown (those in New York, Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, and Montreal are listed) to purchase the proper furniture, table settings, decorations, and finally ingredients. Luncheon hostesses seeking more “authenticity” required guests to come in Chinese costume and acquired a Chinese “boy” to wait on table (if not, the maid could be dressed in Chinese fashion and instructed to shuffle noiselessly). Wisely, Bossé advises her readers to first taste the dishes in Chinatown before trying to cook them. The menus are fairly straightforward, resembling the set feasts that restaurants like the Port Arthur served to wealthy white slumming parties. Her Chinese dinner includes bird’s nest soup, sweet and sour fish, pineapple chicken, duck chow mein, “Gar Lu Chop Suey,” sautéed cucumbers, Chinese mushrooms with green peppers, and the usual assortment of preserved fruits and Chinese cakes for dessert. The following year, Bossé and her sister Winnifred, writing under the pseudonym Onoto Watanna, published their ground-breaking

Chinese-Japanese Cook Book

. This milestone (the first Japanese cookbook written in English and perhaps the second Chinese), representing the cutting edge of cuisine at the time, was a perfect source for the hostess who sought to re-create a bit of Bohemia in her home.

We get another glimpse of how American women used these recipes and the suggestions for Chinese-themed parties in Sinclair Lewis’s 1920 novel

Main Street

. Born in the small town of Sauk Centre, Minnesota, Lewis excelled at describing Middle America in the post–World War I era. In much of his work, Chinese restaurants (“lanterns painted with cherry-blossoms and with pagodas, hung against lattices of lustrous gold and black”) appear prominently as part of the downtown landscape of midwestern towns and cities.

The protagonist of

Main Street

is Carol Kennicott, a young woman from Minneapolis who marries a doctor and goes to live in his dreary, conservative hometown, Gopher Prairie. A few months after arriving, she decides to throw a house-warming party, as people do in the city. She spends weeks on preparations, going to Minneapolis to buy supplies, new furniture, clothes, and a Japanese obi to hang on the wall. Her guests consist of Gopher Prairie’s entire “aristocracy”—doctors, lawyers, businessmen, and their wives. They expect a prim and proper entertainment, followed by a filling meat-and-potatoes meal, but Carol Kennicott has another idea: something “noisy and undignified.” After making her guests play a game she learned in Chicago—in the dark, with no shoes, and on their hands and knees no less—she produces paper Chinese masquerade costumes she has bought for everyone to wear. She also changes her dress, becoming “an airy figure in trousers and a coat of green brocade edged with gold; a high gold collar under a proud chin; black hair pierced with jade pins; a languid peacock fan in an outstretched hand; eyes uplifted to a vision of pagoda towers.”

7

After regaling her guests with an impromptu “Chinese” concert, she leads them “in a dancing procession” to the dining room, where they find blue bowls of chow mein, with lychee nuts and ginger preserved in syrup. “None of them save that city-rounder Harry Haydock had heard of any

Chinese dish except chop sooey. With agreeable doubt they ventured through the bamboo shoots into the golden fried noodles of the chow mein.”

8

The eating guests allow Carol to rest for a minute, and she briefly considers one more gesture to shock them—smoking a cigarette—before dismissing the thought as “obscene.” In the social column of the local weekly, the editor (who attended the event) praises the party and its novel diversions, including the “dainty refreshments served in true Oriental style.” But a few days later, Carol’s best friend tells her what the guests really thought: the party was too expensive, and the Chinese theme too novel: “And it certainly is unfair of them to make fun of your having that Chinese food—chow mein, was it?—and to laugh about your wearing your pretty trousers.”

9

Carol bursts into tears, and no more Chinese food is served in Gopher Prairie. (A few chapters later, however, Carol and her husband escape for a quick trip to Minneapolis, where they visit a “Chinese restaurant that was frequented by clerks and their sweethearts on paydays. They sat at a teak and marble table eating Eggs Foo yung, and listened to a brassy automatic piano, and were altogether cosmopolitan.”)

10

The Chinese restaurant experience is something only urban sophisticates appreciate, at least in Minnesota in the 1920s.