Catherine Price (9 page)

Authors: 101 Places Not to See Before You Die

C

ut off from the rest of Alaska by thirty-five-hundred-foot-tall mountains, covered for most of the year by heavy clouds, the town of Whittier, Alaska, might not exist if it weren’t for World War II. After the Japanese bombed the Aleutian Islands in 1942, the U.S. Army wanted to find a place in Alaska to build a secret military installation—ideally an isolated spot with an ice-free port and bad weather that would make it harder to see from the air. Tucked into the northeast corner of the Kenai Peninsula and cut off from the mainland by the Chugach Mountains, Whittier qualified on all counts.

After deciding on a location, the army’s first task was to build a tunnel. So it began blasting through the granite, and by 1943 had completed a 2.5-mile passageway to Whittier that, until recently, was open only to trains. Next, it built two huge apartment buildings to house the residents of the town.

At its peak in 1960, Whittier’s population was about twelve hundred, but that didn’t last long. When the army pulled out of Whittier, its population dropped to a mere eighty Whittiots, which meant that when the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake killed thirteen people, it wiped out a considerable percentage of the town’s population. As of 2007, Whittier was back up to a whopping 174 residents, but with more people migrating out than coming in, it’s unlikely to ever reach its former peak.

Part of the reason Whittier has never been heavily populated is that until the tunnel was opened to cars, the only way to get there was by sea or rail. Even today, the one-lane tunnel can only accommodate one direction of traffic at a time, and has to alternate between trains and cars. Add in daily maintenance periods and there are times when you can wait more than two hours for the chance to pay the $12 toll.

Of course, this only applies when the tunnel is

open

. It closes each evening around 11, so don’t linger too long if you intend to make it back to Anchorage for the night. What’s more, on April 11, 2009, a large rockslide tumbled onto the highway leading to the tunnel. It was shut down entirely for more than a month, stranding many of the town’s residents and giving new relevancy to the

POW

—

PRISONER OF WHITTIER

—T-shirts that were popular before the tunnel opened to cars.

Begich Towers, the town’s only apartment building—and home to most of Whittier’s residents

Courtesy of the author

Whittier does have a beautiful hiking trail and great wildlife, but be sure to time your visit well—it receives no direct sunlight from November to February and gets more than twenty feet of snow per year.

T

he 1400s were good to Onondaga Lake, a 4.6-square-mile lake that sits northwest of Syracuse, New York. Back then, it enjoyed a privileged status at the heart of the Iroquois Confederacy. Its halcyon days lasted until the nineteenth century, when it became a popular holiday destination, ringed with resorts and restaurants featuring locally caught fish. But once industrial development in Syracuse really kicked in, the lake got screwed.

First was the sewage: as the nearby city of Syracuse grew, its planners designed its water system to discharge the city’s domestic and industrial waste directly into the lake.

Then came the Solvay Process Company, a soda ash producer that opened on Onondaga’s western shore in 1884 and proceeded to release millions of gallons of by-products into the lake per day. That got rid of the company’s trash—but it also killed off most of the coldwater fish.

Pollution eventually forced the resorts and beaches to close—at which point you’d think someone would have realized that using the lake as a garbage can was a bad idea. But instead, Solvay was replaced by the Allied Chemical and Dye Company, which discharged about 165,000 pounds of mercury into the water over the next fifteen years.

Other companies followed Allied’s lead, dumping chemicals like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and chlorinated benzene into the mix.

It was only after the Clean Water Act passed in 1972 that people started trying to clean up Onondaga. The sewage treatment plant was updated; several of the heaviest polluters were shut down. But unfortunately, these efforts came late—almost forty years later, the lake is still unsafe to swim in, and the sediments at its bottom are on the federal Superfund list. A group called the Onondaga Lake Partnership has made admirable progress toward making Onondaga Lake a safe environment for fish and other marine life. But considering the lake’s remaining problems, like large plumes of algae and overflows of untreated sewage, it’s going to be a while before you see me doing laps.

B

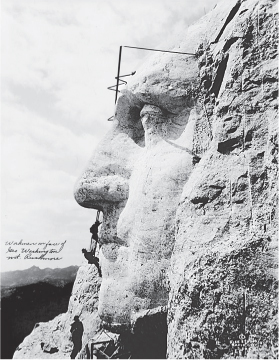

eautiful though it may be, South Dakota doesn’t have much in the way of manmade attractions. But what it lacks in number, it makes up in scale—the presidential portraits on Mount Rushmore, carved into the face of a mountain, are each over sixty feet tall.

Peering out from the mountain, the oversize faces of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt were designed to celebrate the first 150 years of American history. With America more than 230 years old and going (relatively) strong, Mount Rushmore still draws millions of visitors per year.

That’s the part I don’t get, because while Mount Rushmore is an impressive achievement, it’s really not that interesting. There’s no jackalope or fake Tyrannosaurus Rex (see Wall Drug, p. 42); in fact, three of the people featured in the sculpture also appear on the bills you’ll be using to pay the park entrance fee. Take into account the fact that the sculptures were carved into hills considered sacred to the Lakota Sioux, and it starts seeming less like a testament to the American spirit and more like an example of us acting like jerks.

But what really confuses me is the lack of creativity. Unlike many other historical sites, Mount Rushmore never had a purpose besides being a tourist attraction: it was built specifically to draw visitors to South Dakota’s Black Hills. So why not spice things up a bit? Mountaineering guides could lead climbing expeditions up Thomas Jefferson’s nose. An entrepreneurial company could rig a zip line from Teddy Roosevelt’s mustache. Each summer Mount Rushmore does offer sculpting classes, but still. Gazing up at the possibility that is Washington’s forehead, I can’t help but think we could do a little better.

Wikipedia Commons

I

f I’m going to spend an evening shooting guns, I want there to be plenty of adult supervision—especially if half the clientele has never fired one before.

This was not the case at Jackson Arms Shooting Range in southern San Francisco where I attended a handgun-themed bachelor party with a bunch of other firearm neophytes. Housed in what looked like an industrial warehouse, the parking lot was full of pickup trucks with bumper stickers not typically associated with the San Francisco Bay Area, and the walls of the lobby and gift shop were lined with rifles. When my husband jokingly asked whether the shop had ever been held up, our teacher didn’t smile. “No,” he said. “We’re all holstered.”

Holstered he was—when he led our group into a back classroom, I noticed the butts of twin handguns protruding from under his T-shirt. I’d hoped that the fact that he was carrying at least two firearms would mean that he would have a very hands-on approach to teaching us how to use them. But instead, he treated our gun education with the gravitas one might find at an employee training session for a fast-food restaurant.

“What’s this?” the teacher asked, pointing at the back of the room.

“A wall,” someone responded.

“No. The men’s bathroom. Bullets go through walls.” He appeared pleased at this punchline. “Never point your gun at anything other than the target.”

This was good advice, but I wanted more. I wanted to know how the safety worked, and how to tell if it was on. I wanted to know what to do if the bullets jammed, and where the location of the emergency exits were, just in case the person next to me freaked out.

Instead, the teacher gave a quick demonstration of how to load the bullets, and explained how to aim (“Point it toward your target”). Then he handed us plastic caddies filled with handguns and boxes of bullets and let us loose in the firing range, a large concrete room divided into lanes. It looked like a cross between a parking lot and a bowling alley, with one important difference: everyone in it was armed.

Much to my distress, these guns were not tethered to anything, which meant that there was no way to prevent a fellow guest from turning toward you and shooting you in the face. This would not have been such an issue if we had been the only people in the room, but we weren’t. A group of twenty-something men gathered in a lane near us, all jockeying for a chance to shoot. Several loners lurked nearby, making me question whether a violent criminal really would have bothered to tick the box next to

PRIOR FELONIES

when filling out his liability form. But most frightening of all was a woman standing in the next lane, forty-something years old with dyed blond hair. Wearing a pink T-shirt and glasses that had a line of masking tape across the lenses to help steady her sight, she was taking slow, methodical shots with a .45-caliber handgun—not at a bull’s eye, but at the outline of a man’s torso.

W

hat is it about borders? Why are they inherently exhilarating?” asked the

New York Times

in December 2006 in an article about El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, two adjacent cities on opposite sides of the Rio Grande. Its focus was food, but in recent years Juárez has become best known for crime: between January 2008 and early 2009, more than eighteen hundred people were murdered.

The majority of these killings are attributed to drug cartels, but there’s a more systemic problem. The Mexican army is in the midst of an aggressive military effort against the cartels, but its soldiers have also been accused of abusing local police offers. In turn, the police force itself tortures detainees and indulges in other horrific abuse: one woman, a former beauty queen, was allegedly held for three days and repeatedly raped by eight policemen. And then there are the drug cartels themselves. Responsible for public assassinations, gruesome decapitations, and the murders of innocent citizens, they’re waging a bloody fight against one another and anyone who stands in their way.

What’s particularly terrifying about this battle is that many of

Juárez’s victims have little or no connection to the battles raging around them. Innocent people have been shot in broad daylight; in the city of 1.6 million people, there were 17,000 car thefts and 1,650 carjackings in 2008 alone. The U.S. State Department warns that “recent Mexican army and police confrontations with drug cartels have resembled small-unit combat, with cartels employing automatic weapons and grenades” and says that Juárez has become subject to “public shootouts during daylight hours in shopping centers and other public venues.” It recommends staying close to tourist sites, traveling only during the day, using toll roads wherever possible, avoiding ATMs, and, for women in particular, not traveling alone.

The border is indeed exhilarating—but unfortunately for anyone trying to live or visit Ciudad Juárez, not in a good way.

S

ome fights are hard to get worked up about—like the spat between the Sam Kee Building in Vancouver, British Columbia, and the so-called Skinny Building in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, over which structure is the thinnest.

At four feet eleven inches at its base (and six feet on its second story, thanks to bay windows), the Sam Kee Building has been named the skinniest commercial building in the world by both the

Guinness Book of World Records

and Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Like many other slender buildings, it was built partially out of spite: its lot, originally a normal size, got reduced by twenty-four feet when Vancouver expropriated the space to widen Pender Street in 1912. Designed in 1913, the building’s basement actually extends underneath the sidewalk and used to house the only public baths in Vancouver’s Chinatown (not to mention an escape tunnel for nearby opium dens); the upper two stories were devoted to shops and very narrow apartments.

But watch out, Mr. Kee—Pittsburgh’s Skinny Building wants to challenge its claim to be the thinnest commercial space in the world. At five feet two inches wide from top to bottom, the Skinny Building is indeed more consistently emaciated than the top-heavy Sam Kee. What’s more, at three stories tall, it’s a floor higher. Back in the early 2000s, Pat Clark and Al Kovacik—a consultant and architect who were leasing the top two floors of the Skinny Building as an arts venue, sent photographs to Vancouver’s visitors’ center as proof that their building was narrower.

Clark and Kovacik may have had a point, but unfortunately, their argument may now be moot—in 2007, their landlord refused to renew their lease, and the arts venue was forced to close. With that attraction gone, the building’s main draw is purely its diminutive size, which, as anyone who knows someone obsessed with their weight can attest, is really not that interesting.