Candyfloss (13 page)

Authors: Nick Sharratt

‘You can’t force her in if she doesn’t want to

come

,’ said Dad. ‘She’s not our cat.’

‘I so want her to be ours, Dad.’

‘Well, leave her be for now. She’ll hang around if she feels like it.

She’ll

decide whether she’s going to be our cat or not.’

‘Our Lucky,’ I said.

I’d checked up on her ten minutes later. I peered behind every wheelie bin. I peeped under every tarpaulin. I scoured the entire back yard. There was no sign of Lucky.

‘She’ll have gone for a little prowl around, Floss. That’s what cats do,’ said Dad.

‘But she will come back?’

‘Well. Probably,’ said Dad. ‘In her own good time.’

‘Probably isn’t definite enough!’ I wailed. ‘Oh Lucky, where are you? You will come back, won’t you? You really badly want to be our little lucky black cat, don’t you?’

I listened hard for a tiny mew. If Lucky could hear me she kept quiet.

I’d paced the back yard all the following evening, but there was still no sign of her. I got Dad to open a fresh tin of tuna and I poured out another saucer of milk and waited tensely, hour after hour.

A big ginger tom came prowling past but I hid Lucky’s gourmet tea from him. Lucky herself didn’t come near. I left her food out overnight and it was

nearly

all gone in the morning – but I couldn’t tell if Lucky herself had eaten it, or whether the ginger tom had come back.

On Friday Dad had said gently that maybe we couldn’t count on Lucky returning.

‘Maybe she’s gone back home to her real owners. Or maybe she’s happy fending for herself, being a little street cat.’

‘She’d be much happier with us,’ I said. ‘She’ll come back, Dad, in her own good time, like you said.’

If she

had

come back during the night and had a nap cuddled up in my T-shirt, she hadn’t hung around to say hello this morning.

I picked up my sodden jeans and T-shirt and squished my way back into the house. Dad was in the kitchen in his dressing gown, yawning and scratching.

‘Floss? Have you been out to play in the pouring rain?’ he said. He held up my clothes. ‘For goodness’ sake! We’ll have to put them straight back in the wash. You should have kept them clean for visiting Rhiannon.’

I leaned against the kitchen table, helping myself to cornflakes straight from the packet. ‘Lucky might just have been in the back yard last night,’ I said.

‘Hmm. Well, we could do with some luck right

this

minute,’ said Dad, looking through his post.

There was a handful of bills and one scary white envelope with

IMPORTANT

stamped in big red letters. Dad opened it up, read it quickly, shoved it in his dressing-gown pocket and then slumped beside me. He reached in the cornflakes packet for a snack. His hand was trembling and cornflakes spilled over the kitchen floor.

‘What’s the matter, Dad?’ My voice sounded croaky because my throat was so dry. I swallowed hard but the cornflakes in my mouth wouldn’t go away.

‘It’s our notice to quit,’ said Dad. He breathed out, so hard that the cornflakes packet wavered and nearly fell over. ‘I wrote to them begging for more time, explaining I’m now looking after my daughter full time. I thought that might just sway them. I mean, what sort of heartless monsters would render an innocent little kid homeless? Well, now I’ve found out. We’ve got two weeks, Floss. Two flipping weeks and then we have to hand over the keys or they’ll send in the heavies.’ Dad bent forward, resting his head on the table.

‘Dad?’ I whispered.

I lowered my own head, staring at him. His eyes were closed.

‘Please, Dad! Sit up. It’ll be all right,’ I said,

stroking

his head.

Dad groaned. ‘I’ve let you down, darling.’

‘No you haven’t! Here, Dad, let me make you a cup of tea.’

I bustled around boiling the kettle and fetching a mug and milk and tea bags. I knew Dad would look up when it came to me pouring the boiling water, just in case I wasn’t doing it safely enough. Just as I’d thought, he sat up straight the second the kettle switched off.

‘Here, I’ll do it,’ Dad said, sighing.

He made us both a cup of tea and then sat sipping his, staring all around the kitchen. He looked at the greasy walls and the ancient cooker and the higgledy-piggledy cupboards and the cracked lino tiles on the floor. He stood up and stroked some silly old paintings I’d done at nursery school, each a red blobby figure with a big smiley mouth, all bearing the same title:

My Dad

. He picked up my plasticine rabbit models on the windowsill and my lopsided plaster ashtray and the plate I’d painted with big purple pansies because Dad said they were his favourite flower.

‘All my treasures,’ Dad mumbled, as if the kitchen was crammed with wondrous antiques.

‘We’ll pack everything and take it with us, Dad,’ I said.

‘To decorate our cardboard box?’ said Dad. He

shook

his head. ‘Sorry, sorry, I’m getting maudlin. No, I’ll manage. Maybe one of my old biker mates will let me kip in a corner of his living room for a bit, just till I get myself sorted.’

‘Will they let me have a corner too, Dad?’ I asked anxiously.

‘You’re not sleeping on floors, darling. No, I’ll wait till this evening, when it’s morning in Australia, and then I’ll phone your mum. We’ll whizz you over to Sydney.’

‘No, Dad!’

‘Yes, Floss,’ said Dad firmly. ‘Now, you go and find yourself some decent dry clothes and forget all this bother for the moment. You’re going to have a lovely day with Rhiannon.’

I wasn’t at all sure about that. I dressed myself in my old jeans and my old stripy T-shirt, after burying my head in them to see if they smelled. It was so difficult to tell at home in the café because it

all

smelled so cosily of cooking.

I brushed my hair and I brushed my teeth and I brushed my shoes. I did this varied brushing ultra thoroughly, and at each stroke of the brush I made a wish that our luck would change and that somehow or other Dad could stay cooking his chip butties for ever.

Billy the Chip came in to mind the café while Dad was taking me to Rhiannon’s. He was

clutching

his

Racing Post

.

‘Come on, young Flossie, pick me a winner,’ he said.

‘Oh Mr Chip, I’m rubbish at picking winners. Birthday Girl was hopeless, and Iced Bun was worse.’

‘Have another go, darling.’

‘What, you think it’ll be third time lucky?’ I said.

‘Yes!’ said Billy the Chip. ‘Look! Third Time Lucky is running at Doncaster! We’ve got to back it now. What about you, Charlie? Shall I put something on for you?’

‘I haven’t got anything left to bet with, mate. I think it might be a bit of a waste anyway. Look at the odds. It hasn’t got a chance.’

12

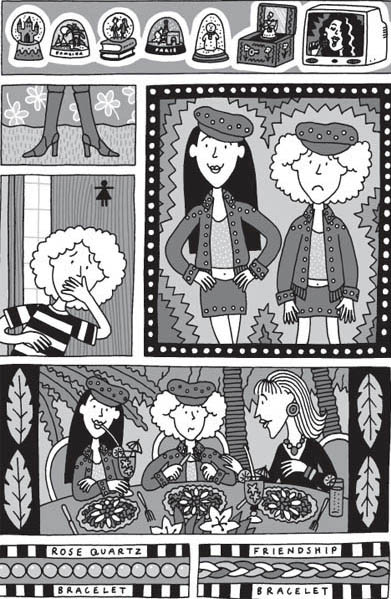

RHIANNON WAS ESPECIALLY

sweet to me. She was almost like the

old

Rhiannon, before she started thinking Margot wonderful. And I felt almost like the old Floss, when I still had two homes and I could see Mum whenever I wanted.

We went to play in Rhiannon’s beautiful blue bedroom, and it was so

peaceful

lying back on her soft flowery duvet and seeing the clean white paint and fresh blue ruffles. It felt as if we were floating up into the sky. Rhiannon let me shake all her snowdomes and wind up her Cinderella musical box and flick from channel to channel on her own little white television.

She let me try on all her coolest clothes. She even let me try walking in her brand-new boots with pointy toes and real heels. She didn’t want to try on my jeans and T-shirt, so I let her wear my birthday-present rose-quartz bracelet. It looked very pretty on her slim white wrist. I

asked

her where her friendship bracelet was.

‘I don’t know,’ she said, shrugging. ‘Think I must have lost it.’

‘Oh. Well. Never mind,’ I said. ‘I’ll make you another if you like. Tell you what, we could use that kit I gave you and make each other a friendship bracelet now.’

Rhiannon wrinkled her forehead. ‘Like, boring!’ she said. ‘No, we’re going shopping – I

said

. Mum’s taking us to Green Glades.’

Rhiannon’s mum drove us there in her big Range Rover. Rhiannon and I knelt up at the back and made faces at people in the cars behind.

‘I bet you wish you had a big car like our Range Rover,’ said Rhiannon.

‘It’s lovely – but actually my dad’s van is just as big,’ I said.

‘Yeah, but, like, that’s just a transit van,’ said Rhiannon.

They obviously didn’t compare so I kept my mouth shut. I was starting to feel a bit sick. I hadn’t realized Green Glades was so far away. I wriggled round in my seat and stared straight ahead. My jeans were starting to be a bit too small for me. They pressed uncomfortably into my tummy. I closed my eyes, praying that I wasn’t going to disgrace myself.

‘Hey, don’t go to sleep on me, Floss!’ said Rhiannon.

‘No, no, leave her be, darling,’ said Rhiannon’s mother. ‘She looks as if she could do with a good sleep. She’s looking so peaky, poor lamb. I know her dad is doing his best but I bet he doesn’t get her to bed on time.’

I wanted to argue, but I knew if I sat up and opened my mouth I would actually start spouting vomit. I stayed still as a statue, eyes shut, tummy clenched, sweat trickling down inside my T-shirt with the effort of keeping my breakfast in place.

Seemingly many many years later we got to Green Glades and parked the car. I rushed to the nearest ladies, and when the cubicle door shut me away from Rhiannon and her mum I threw up as silently as possible.

‘Oh darling, you do look weak and feeble,’ Rhiannon’s mother cooed, when I staggered out. ‘You haven’t been sick, have you?’

‘No!’ I said emphatically, because she’d only start on about my dad’s chip butties. I suddenly soooo wanted my mum, who would know exactly how to deal with Rhiannon’s mother. I hated being the poor sad sickly girl, especially when I was

feeling

so poor and sad and sickly.

I wanted to talk to her on the phone. Dad was going to phone her tonight to tell her that he thought I should go to Australia. My stomach started churning again. I wanted Mum but I

wanted

Dad too. I couldn’t bear the thought of leaving him. He’d said the heavies would move in. I didn’t really know what a heavy was. I pictured an army of huge red-faced prickly-headed guys, all of them punching my poor dad and then kicking him out of our café with their big heavy boots as if he was a bag of rubbish. I saw him sitting in the gutter, crawling inside his cardboard box.

I had to run right back to the ladies’ loo and throw up all over again. I didn’t even have anything to be sick with any more; it was just horrible bile stuff. I couldn’t fool Rhiannon and her mother this time. I suffered a lecture about suitable diet for the next half-hour, though I told them truthfully I’d simply had a small bowl of cornflakes for my breakfast.

‘Margot has the most amazing mango and pineapple smoothies for her breakfast. We made them ourselves. It was

so

cool,’ said Rhiannon.

‘When were you having breakfast with Margot?’ I said.

‘When she had this sleepover,’ Rhiannon said airily.

I was stunned. I had been so scared of upsetting Rhiannon by having Susan over for tea, and yet here she was casually telling me that she had actually

stayed the night

at Margot’s.

‘What?’ said Rhiannon, seeing my expression. ‘

Oh

Floss, lighten up. It’s

OK

. You don’t have to be, like,

jealous

.’ She actually laughed at me.

‘I’m

not

jealous,’ I mumbled foolishly.

‘Don’t worry, dear. You’re still Rhiannon’s special friend,’ said Rhiannon’s mum.

She didn’t say ‘best’ friend. ‘Special’ made me sound embarrassing and needy, the poor little saddo you had to be nice to because you felt so sorry for her.

I felt my cheeks burning. I didn’t

want

Rhiannon as my friend any more, best or special. I wished wished wished I’d made real friends with Susan.

I was stuck with Rhiannon and her mother. We went up and down every single arcade and walkway of the Green Glades shopping centre. I’d have liked it if I was there with

my

mum. We’d look at things together and try on different stuff and strike mad poses like fashion models and tell each other we looked drop-dead gorgeous.

Rhiannon and her mother took their shopping

seriously

. They tried on outfit after outfit, reciting the designer labels as if they were magic charms.

‘You must try on anything you fancy too, Floss,’ said Rhiannon’s mum. ‘I’m determined to treat you, darling. We can’t have you wandering about like a sad little scarecrow.’

She bought me new white socks. She wanted to buy me new shoes too, but I said that my trainers

had

been a special birthday present from my mum and I wanted to wear them all the time.

‘They’re starting to look a bit shabby already, dear,’ said Rhiannon’s mum, but she didn’t press it.

She

did

press me to choose some new clothes. She didn’t

say

anything disparaging about my jeans and T-shirt, but she shook her head and sighed, so it was plain what she thought of them.