Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (63 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

48. Big Foot in death. Photographed at the Wounded Knee battlefield. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

“It sounded much like the sound of tearing canvas, that was the crash,” Rough Feather said. Afraid-of-the-Enemy described it as a “lightning crash.”

4

Turning Hawk said that Black Coyote “was a crazy man, a young man of very bad influence and in fact a nobody.” He said that Black Coyote fired his gun and that “immediately the soldiers returned fire and indiscriminate killing followed.”

5

In the first seconds of violence, the firing of carbines was deafening, filling the air with powder smoke. Among the dying who lay sprawled on the frozen ground was Big Foot. Then there was a brief lull in the rattle of arms, with small groups of Indians and soldiers grappling at close quarters, using knives, clubs, and pistols. As few of the Indians had arms, they soon had to flee, and then the big Hotchkiss guns on the hill opened up on them, firing almost a shell a second, raking the Indian camp, shredding the tepees with flying shrapnel, killing men, women, and children.

“We tried to run,” Louise Weasel Bear said, “but they shot us like we were a buffalo. I know there are some good white people, but the soldiers must be mean to shoot children and women. Indian soldiers would not do that to white children.”

“I was running away from the place and followed those who were running away,” said Hakiktawin, another of the young women. “My grandfather and grandmother and brother were killed as we crossed the ravine, and then I was shot on the right hip clear through and on my right wrist where I did not go any further as I was not able to walk, and after the soldier picked me up where a little girl came to me and crawled into the blanket.”

6

When the madness ended, Big Foot and more than half of his people were dead or seriously wounded; 153 were known dead, but many of the wounded crawled away to die afterward. One estimate placed the final total of dead at very nearly three hundred of the original 350 men, women, and children. The soldiers lost twenty-five dead and thirty-nine wounded, most of them struck by their own bullets or shrapnel.

After the wounded cavalrymen were started for the agency at

Pine Ridge, a detail of soldiers went over the Wounded Knee battlefield, gathering up Indians who were still alive and loading them into wagons. As it was apparent by the end of the day that a blizzard was approaching, the dead Indians were left lying where they had fallen. (After the blizzard, when a burial party returned to Wounded Knee, they found the bodies, including Big Foot’s, frozen into grotesque shapes.)

The wagonloads of wounded Sioux (four men and forty-seven women and children) reached Pine Ridge after dark. Because all available barracks were filled with soldiers, they were left lying in the open wagons in the bitter cold while an inept Army officer searched for shelter. Finally the Episcopal mission was opened, the benches taken out, and hay scattered over the rough flooring.

It was the fourth day after Christmas in the Year of Our Lord 1890. When the first torn and bleeding bodies were carried into the candlelit church, those who were conscious could see Christmas greenery hanging from the open rafters. Across the chancel front above the pulpit was strung a crudely lettered banner:

PEACE ON EARTH, GOOD WILL TO MEN.

I did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud, and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream … the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.

—

BLACK ELK

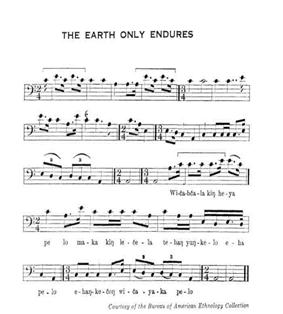

The old men say the earth only endures.

You spoke truly.

You are right.

49. “They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it.” Reproduced from the collections of the Library of Congress. Photograph by E. S. Curtis.

Dorris Alexander “Dee” Brown (1908–2002) was the author of many fiction and nonfiction books about the American West and the Civil War. He is best remembered for his celebrated chronicle

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

, which is widely credited with exposing the systematic destruction of American Indian tribes to a world audience.

Born in Alberta, Louisiana, Brown grew up in the small town of Stephens in Ouachita County, Arkansas. His father died when he was five years old, and he was raised by his mother and maternal grandmother, who proved instrumental in igniting his interest in reading at an early age. His grandmother told him stories from the Civil War, as well as tales of Davy Crockett, the frontier hero who had been an acquaintance of her father’s. A regard for Pawnee baseball pitcher Moses Yellowhorse, as well as Brown’s friendship with an Indian peer, helped fuel his lifelong interest in the plight and history of American Indians.

As an adolescent, Brown was drawn to literature, particularly the works of John Dos Passos, William Faulkner, Jack London, and Robert Louis Stevenson. His interest in history was reinforced when a teacher introduced him to the expedition of Lewis and Clark. He was also drawn to journalism, and published his first story at the age of fifteen in a neighborhood tabloid he started with friends. Brown worked as both a reporter and a printer before enrolling at Arkansas State Teachers College (now the University of Central Arkansas), where he met his future wife, Sally Stroud. Brown later earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in library science from George Washington University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, respectively. In the years between these studies, during World War II, he was drafted to into the U.S. Army and served as a librarian in the Department of Agriculture, a position that gave him frequent access to the National Archives.

Brown began publishing magazine articles in the 1930s, followed by a novel in 1942. His writing career took off in 1948, with the publication of the first of three books of frontier history he had co-authored with Martin Schmitt, titled

Fighting Indians of the West

. Legendary Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins oversaw the series.

Brown went on to publish more than thirty books during his lifetime. His novels, which unite a love of storytelling and high adventure with rigorous historical accuracy, include

Action at Beecher Island

,

Cavalry Scout

,

Conspiracy of Knaves

,

Killdeer Mountain

,

The Girl from Fort Wicked

, and

Creek Mary’s Blood

, a notable saga about five generations of one American Indian family. Among his extensively researched works of nonfiction are

The Gentle Tamers

, about the role of women in the Old West;

Hear That Lonesome Whistle Blow

, a history of the beginnings of the railroads; and

The Year of the Century: 1876

, a look at America at the time of its first centennial. Brown’s most famous title is

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

(1970). During years of research, Brown compiled eyewitness accounts, tribal histories, and other archived documents, synthesizing them into a record of the deadly frontier conflicts in the late nineteenth century from an American Indian perspective. The book has been translated into more than thirty languages over the years, and continues to be translated for new audiences today. It remains one of the definitive works on American history, as it revealed a devastating side to western expansion.

Brown died in 2002 in Little Rock, Arkansas. He was ninety-four and at work on a new novel that was to be a sequel to

The Way to Bright Star,

which he published at the age of 90.

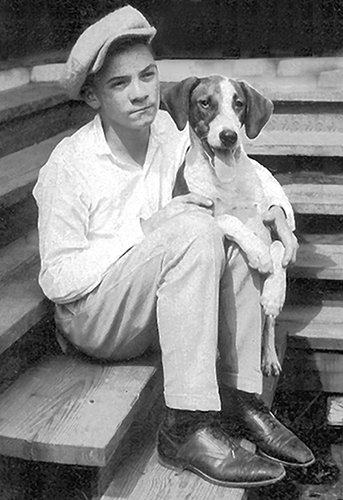

Infant Dee Brown with his half-siblings, Mildred and Daniel Brown, around 1908.

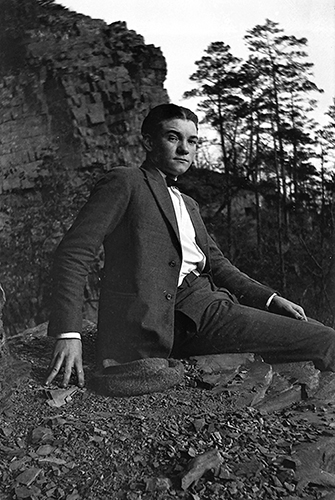

A young Brown in Arkansas, before 1920. (Photo courtesy of the Dee Brown LLC.)