Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (61 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

After nine days of discussion, a majority of the Brulés followed Crook’s advice and signed. The first signature on the agreement was that of Crow Dog, the assassin of Spotted Tail.

At Pine Ridge in June, the commissioners had to deal with Red Cloud, who demonstrated his power by surrounding the council with several hundred of his mounted warriors. Although Red Cloud and his loyal lieutenants stood firm, the commissioners managed to secure about half of the Oglalas’ signatures. To make up the difference they moved on to the smaller agencies, obtaining signatures at Lower Brulé, Crow Creek, and

Cheyenne River. On July 27 they arrived at Standing Rock. Here the decision would be made. If a majority of the Hunkpapas and Blackfoot Sioux refused to sign, the agreement would fail.

Sitting Bull attended the first councils but remained silent. His presence was all that was needed to maintain a solid wall of opposition. “The Indians gave close attention,” Crook said, “but gave no indication of favor. Their demeanor was rather that of men who had made up their minds and listened from curiosity as to what new arguments could be advanced.”

John Grass was chief spokesman for the Standing Rock Sioux. “When we had plenty of land,” he said, “we could give it to you at your own prices, whatever you had in mind to give, but now we have come down to the small portion there is to spare, and you wish to buy the balance. We are not the ones who are offering our lands for sale. It is the Great Father that is after us to sell the land. That is the reason that the price that is put on the land here we think is not enough, therefore we don’t want to sell the land at that price.”

15

Sitting Bull and his followers, of course, did not want to sell at any price. As White Thunder had told the Dawes commission six years earlier, their land was “the dearest thing on earth” to them.

After several days of fruitless discussion, Crook realized that he could win no converts in general councils. He enlisted agent James McLaughlin in a concerted effort to convince individual Indians that the government would take their land away if they refused to sell. Sitting Bull remained unyielding. Why should the Indians sell their land in order to save the United States government the embarrassment of breaking a treaty to get it?

White Hair McLaughlin arranged secret meetings with John Grass. “I talked with him until he agreed that he would speak for its ratification and work for it,” McLaughlin said afterward. “Finally we fixed up the speech he was to make receding from his former position gracefully, thus to bring him the active support of the other chiefs and settle the matter.”

16

Without informing Sitting Bull, McLaughlin arranged for a final meeting with the commissioners on August 3. The agent

stationed his Indian police in a four-column formation around the council grounds to prevent any interruptions by Sitting Bull or any of his ardent supporters. John Grass had already delivered the speech, which McLaughlin had helped him write, before Sitting Bull forced his way through the police and entered the council circle.

For the first time he spoke: “I would like to say something unless you object to my speaking, and if you do I will not speak. No one told us of the council, and we just got here.”

Crook glanced at McLaughlin. “Did Sitting Bull know that we were going to hold a council?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” McLaughlin lied. “Yes, sir, everybody knew it.”

17

At this moment John Grass and the chiefs moved forward to sign the agreement. It was all over. The Great Sioux Reservation was broken into small islands around which would rise the flood of white immigration. Before Sitting Bull could get away from the grounds, a newspaperman asked him how the Indians felt about giving up their lands.

“Indians!” Sitting Bull shouted. “There are no Indians left but me!”

In the Drying Grass Moon (October 9, 1890), about a year after the breaking up of the Great Reservation, a Minneconjou from the Cheyenne River agency came to Standing Rock to visit Sitting Bull. His name was Kicking Bear, and he brought news of the Paiute Messiah, Wovoka, who had founded the religion of the Ghost Dance. Kicking Bear and his brother-in-law, Short Bull, had returned from a long journey beyond the Shining Mountains in search of the Messiah. Hearing of this pilgrimage, Sitting Bull had sent for Kicking Bear in order to learn more about the Ghost Dance.

Kicking Bear told Sitting Bull of how a voice had commanded him to go forth and meet the ghosts of Indians who were to return and inhabit the earth. On the cars of the Iron Horse he and Short Bull and nine other Sioux had traveled far toward the place where the sun sets, traveled until the railroad stopped. There they were met by two Indians they had never seen before, but who greeted them as brothers and gave them meat and

bread. They supplied the pilgrims with horses and they rode for four suns until they came to a camp of Fish Eaters (Paiutes) near Pyramid Lake in Nevada.

The Fish Eaters told the visitors that Christ had returned to earth again. Christ must have sent for them to come there, Kicking Bear said; it was foreordained. To see the Messiah they had to make another journey to the agency at Walker Lake.

For two days Kicking Bear and his friends waited at Walker Lake with hundreds of other Indians speaking in dozens of different tongues. These Indians had come from many reservations to see the Messiah.

Just before sundown on the third day the Christ appeared, and the Indians made a big fire to throw light on him. Kicking Bear had always thought that Christ was a white man like the missionaries, but this man looked like an Indian. After a while he rose and spoke to the waiting crowd. “I have sent for you and am glad to see you,” he said. “I am going to talk to you after a while about your relatives who are dead and gone. My children, I want you to listen to all I have to say to you. I will teach you how to dance a dance, and I want you to dance it. Get ready for your dance, and when the dance is over, I will talk to you.” Then he commenced to dance, everybody joining in, the Christ singing while they danced. They danced the Dance of the Ghosts until late at night, when the Messiah told them they had danced enough.

18

Next morning, Kicking Bear and the others went up close to the Messiah to see if he had the scars of crucifixion which the missionaries on the reservations had told them about. There was a scar on his wrist and one on his face, but they could not see his feet, because he was wearing moccasins. Throughout the day he talked to them. In the beginning, he said, God made the earth, and then sent the Christ to earth to teach the people, but white men had treated him badly, leaving scars on his body, and so he had gone back to heaven. Now he had returned to earth as an Indian, and he was to renew everything as it used to be and make it better.

In the next springtime, when the grass was knee high, the earth would be covered with new soil which would bury all the white men, and the new land would be covered with sweet grass

and running water and trees. Great herds of buffalo and wild horses would come back. The Indians who danced the Ghost Dance would be taken up in the air and suspended there while a wave of new earth was passing, and then they would be set down among the ghosts of their ancestors on the new earth, where only Indians would live.

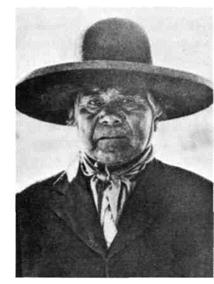

44. Wovoka, the Paiute Messiah. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

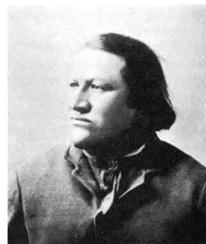

45. Kicking Bear. Photo by David F. Barry, from the Denver Public Library Western Collection.

46. Short Bull of the Sioux. Photo by David F. Barry, from the Denver Public Library

47. John Grass. Photo by David F. Barry, from the Denver Public Library Western Collection.

After a few days at Walker Lake, Kicking Bear and his friends learned how to dance the Ghost Dance, and then they mounted their horses to return to the railroad. As they rode along, the Messiah flew above them in the air, teaching them songs for the new dance. At the railroad, he left them, telling them to return to their people and teach what they had learned. When the next winter was passed, he would bring the ghosts of their fathers to meet them in the new resurrection.

After returning to Dakota, Kicking Bear had started the new dance at Cheyenne River, Short Bull had brought it to Rosebud, and others were introducing it at Pine Ridge. Big Foot’s band of Minneconjous, Kicking Bear said, was made up mostly of women who had lost husbands or other male relatives in fights with Long Hair and Three Stars and Bear Coat; they danced until they fainted, because they wanted to bring their dead warriors back.

Sitting Bull listened to all that Kicking Bear had to relate about the Messiah and the Ghost Dance. He did not believe it was possible for dead men to return and live again, but his people had heard of the Messiah and were fearful he would pass them by and let them disappear when the new resurrection came, unless they joined in the dancing. Sitting Bull had no objections to his people dancing the Ghost Dance, but he had heard that agents at some reservations were bringing soldiers in to stop the ceremonies. He did not want soldiers coming in to frighten and perhaps shoot their guns at his people. Kicking Bear replied that if the Indians wore the sacred garments of the Messiah—Ghost Shirts painted with magic symbols—no harm could come to them. Not even the bullets of the Bluecoats’ guns could penetrate a Ghost Shirt.

With some skepticism, Sitting Bull invited Kicking Bear to remain with his band at Standing Rock and teach them the Dance of the Ghosts. This was in the Moon of Falling Leaves,

and across the West on almost every Indian reservation the Ghost Dance was spreading like a prairie fire under a high wind. Agitated Indian Bureau inspectors and Army officers from Dakota to Arizona, from Indian Territory to Nevada, were trying to fathom the meaning of it. By early autumn the official word was: Stop the Ghost Dancing.

“A more pernicious system of religion could not have been offered to a people who stood on the threshold of civilization,” White Hair McLaughlin said. Although he was a practicing Catholic, McLaughlin, like most other agents, failed to recognize the Ghost Dance as being entirely Christian. Except for a difference in rituals, its tenets were the same as those of any Christian church.