Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (57 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

In September the Chiricahuas at San Carlos were alarmed by a cavalry demonstration near their camp. Rumors were flying everywhere; it was said that the Army was preparing to arrest all leaders who had ever been hostile. One night late in the month, Geronimo, Juh, Naiche, and about seventy Chiricahuas slipped out of White Mountain and raced southward for their old Sierra Madre stronghold in Mexico.

Six months later (April, 1882), well armed and equipped, the Chiricahuas returned to White Mountain. They were determined to free all their people and any other Apaches who wanted to return to Mexico with them. It was an audacious enterprise. They galloped into Chief Loco’s camp and persuaded most of the remaining Chiricahuas and Warm Springs Apaches to leave for Mexico.

In swift pursuit came six companies of cavalry commanded by Colonel George A. Forsyth. (He had survived the Battle When Roman Nose Was Killed; see

chapter seven

.) At Horse

Shoe Canyon, Forsyth caught up with the fleeing Apaches, but in a brilliant rearguard action the Indians held off the troopers long enough for the main body to cross into Mexico. Here disaster struck from an unexpected source. A Mexican infantry regiment stumbled upon the Apache column, slaughtering most of the women and children who were riding in front.

Among the chiefs and warriors who escaped were Loco, Naiche, Chato, and Geronimo. Embittered, their ranks depleted, they soon joined forces with old Nana and his guerrillas. For all of them, it was now a war of survival.

Each recent outbreak at White Mountain had brought an increase in the number of soldiers. They swarmed everywhere—at Fort Thomas, Fort Apache, Fort Bowie—and each increase brought more unrest among the Apaches on the reservation, more flights to Mexico, with the inevitable raiding against ranchers along the escape routes.

To bring order out of chaos, the Army again called on General George Crook—quite a different man from the one who had left Arizona ten years earlier to go north to fight the Sioux and Cheyennes. He had learned from them and from the Poncas during the trial of Standing Bear that Indians were human beings, a viewpoint that most of his fellow officers had not yet accepted.

On September 4, 1882, Crook assumed command of the Department of Arizona at Whipple Barracks, and then hurried on to the White Mountain reservation. He held councils with the Apaches at San Carlos and Fort Apache; he searched out individual Indians and talked privately with them. “I discovered immediately that a general feeling of distrust of our people existed among all the bands of the Apaches,” he reported. “It was with much difficulty that I got them to talk, but after breaking down their suspicions they conversed freely with me. They told me … that they had lost confidence in everybody, and did not know whom or what to believe; that they were constantly told, by irresponsible parties, that they were to be disarmed, that they were to be attacked by troops on the reservation, and removed from their country; and that they were fast arriving at the conclusion that it would be more manly to die fighting than to be

thus destroyed.” Crook was convinced that the reservation Apaches “had not only the best reasons for complaining, but had displayed remarkable forbearance in remaining at peace.”

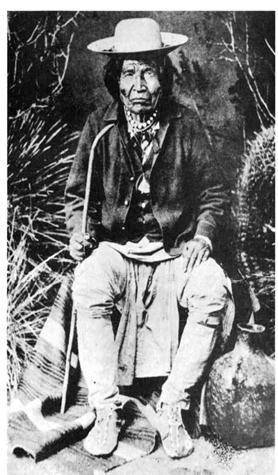

43. Nana. Courtesy of Arizona Historical Society.

Early in his investigations he discovered that the Indians had been plundered “of their rations and of the goods purchased by the government for their subsistence and support, by rascally agents and other unscrupulous white men.” He found plenty of evidence that white men were trying to arouse the Apaches to violent action so that they could be driven from the reservation, leaving it open for land-grabbing.

6

Crook ordered immediate removal of all white squatters and miners from the reservation, and then demanded complete cooperation from the Indian Bureau in introducing reforms. Instead of being forced to live near San Carlos or Fort Apache, the different bands were given the right to choose any part of the reservation to build their homes and ranches. Hay contracts would be given to Apaches instead of to white suppliers; the Army would buy all the excess corn and vegetables the Indians could raise, paying for it in cash. They would be expected to govern themselves, to reorganize their police and hold their own courts, as they had done under John Clum. Crook promised that they would see no soldiers on their reservation unless they found it impossible to control themselves.

At first the Apaches were skeptical. They remembered Crook’s harsh ways in the old days when he was the Gray Wolf hunting down Cochise and the Chiricahuas, but they soon discovered that he meant what he said. Rations became more plentiful, the agents and traders no longer cheated them, there were no soldiers to bully them, and the Gray Wolf encouraged them to build up their herds and seek out better places to grow corn and beans. They were free again, so long as they remained within the reservation.

But they could not forget their relatives who were truly free in Mexico, and there were always a few young men slipping southward, a few returning with exciting news of adventures and good times.

Crook also gave much thought to the Chiricahuas and Warm Springs Apaches in Mexico. He knew it was only a matter of time before they would raid once again across the border, and

he knew he must be ready for them. The United States government had recently signed an agreement with the Mexican government permitting soldiers of each country to cross the border in pursuit of hostile Apaches. He was preparing to take advantage of this agreement, hoping that by doing so he could keep the Arizona and New Mexico civilians from forcing him to start a war.

“It is too often the case,” Crook said, “that border newspapers … disseminate all sorts of exaggerations and falsehoods about the Indians, which are copied in papers of high character and wide circulation, in other parts of the country, while the Indians’ side of the case is rarely ever heard. In this way the people at large get false ideas with reference to the matter. Then when the outbreak does come public attention is turned to the Indians, their crimes and atrocities are alone condemned, while the persons whose injustice has driven them to this course escape scot-free and are the loudest in their denunciations. No one knows this fact better than the Indian, therefore he is excusable in seeing no justice in a government which only punishes him, while it allows the white man to plunder him as he pleases.”

The thought of another guerrilla war with the Apaches aroused the utmost abhorrence in Crook. He knew that it was practically impossible to subdue them in the rugged country where the fighting would have to be done. “With all the interests at stake we cannot afford to fight them,” he admitted frankly. “We are too culpable, as a nation, for the existing condition of affairs. It follows that we must satisfy them that hereafter they shall be treated with justice, and protected from inroads of white men.

7

Crook believed that he could convince Geronimo and the other guerrilla leaders of his good intentions—not by fighting them but by talking with them. The best place for this would be in one of their own Mexican strongholds, where there would be no unscrupulous promoters of Indian wars or rumor-spreading newspapers to stir up a profit-making, land-grabbing war.

While he waited for a border raid to give him an excuse to enter Mexico, Crook quietly put together his “expeditionary force.” It consisted of about fifty carefully chosen soldiers and

civilian interpreters, and about two hundred young Apaches from the reservation, many of whom at one time or another had been raiders in Mexico. In the early weeks of 1883 he moved part of this force down to the tracks of the new Southern Pacific Railroad, which streaked across Arizona to within about fifty miles of the border. On March 21 three minor chiefs—Chato, Chihuahua, and Bonito—raided a mining camp near Tombstone. As soon as Crook learned of the incident he began final preparations for his Mexican entry. Not until after weeks of searching, however, did his scouts find the location of the Chiricahuas’ base camp in the Sierra Madres of Mexico.

In that Season When the Leaves Are Dark Green (May), Geronimo led a raid against Mexican ranchers to obtain cattle. Mexican soldiers pursued them, but Geronimo ambushed the soldiers, punished them severely, and escaped. As the Apaches were returning to their base, one of the men who had been left behind as a guard met Geronimo and told him that the Gray Wolf (Crook) had captured the camp and all the women and children.

Jason Betzinez, one of Geronimo’s cousins who was riding with the Apache party, afterward told of how Geronimo chose two of his older warriors to go down with a truce flag and find out what the Gray Wolf had come for. “Instead of returning to where Geronimo stood,” Betzinez said, “the two men came back halfway up the mountain and called for us all to come down. … Our warriors descended the mountainside, went up to General Crook’s tent, where, after a lengthy conference between the leaders, we all surrendered to the general.”

8

Actually Geronimo had three long parleys with Crook before they came to an agreement. The Apache leader declared that he had always wanted peace but that he had been ill-treated at San Carlos by bad white men. Crook agreed that this was probably true, but if Geronimo wanted to return to the reservation the Gray Wolf would see that he was treated fairly. All Chiricahuas who returned, however, would have to work at farming and stock-raising to make their own livings. “I am not taking your arms from you,” Crook added, “because I am not afraid of you.”

9

Geronimo liked Crook’s blunt manner, but when the general

announced that he must start his column back to Arizona in a day or so, Geronimo decided to test him, to make certain that Crook truly trusted him. The Apache leader said it would require several months to round up all his people. “I will remain here,” he said, “until I have gathered up the last man, woman, and child of the Chiricahuas.” Chato would also remain to assist him. Together they would bring all the people to San Carlos.

10

To Geronimo’s surprise, Crook agreed to the proposition. On May 30 the column started northward. With it went 251 women and children and 123 warriors, including Loco, Mangas (Mangas Colorado’s son), Chihuahua, Bonito, even wrinkled old Nana—all the war leaders except Geronimo and Chato.

Eight months passed, and then it was Crook’s turn to be surprised. True to their word, Geronimo and Chato crossed the border in February, 1884, and were escorted to San Carlos. “Unfortunately, Geronimo made the mistake of driving along with him a large herd of cattle which he had stolen from the Mexicans,” Jason Betzinez said. “This seemed quite proper to Geronimo, who felt that he was only providing a good supply of food for his people. The authorities, taking a different view, pried the cattle loose from the chief.”

11

The honest Gray Wolf ordered the cattle sold, and then he returned the proceeds of $1,762.50 to the Mexican government for distribution to the original owners if they could be found.

For more than a year General Crook could boast that “not an outrage or depredation of any kind” was committed by the Indians of Arizona and New Mexico. Geronimo and Chato vied with each other in the development of their

ranchos,

and Crook kept a watchful eye on their agent to see that he issued adequate supplies. Outside the reservation and the Army posts, however, there was much criticism of Crook for being too easy on the Apaches; the newspapers that he had condemned for disseminating “all sorts of exaggerations and falsehoods about the Indians” now turned on him. Some of the rumor mongers went so far as to claim that Crook had surrendered to Geronimo in Mexico and had made a deal with the Chiricahua leader in order to escape alive. As for Geronimo, they made a special demon of him, inventing atrocity stories by the dozens and calling on

vigilantes to hang him if the government would not. Mickey Free, the Chiricahuas’ official interpreter, told Geronimo about these newspaper stories. “When a man tried to do right,” Geronimo commented, “such stories ought not to be put in the newspapers.”

12

After the Corn Planting Time (spring of 1885), the Chiricahuas grew discontented. There was little for the men to do except draw rations, gamble, quarrel, loaf, and drink tiswin beer. Tiswin was forbidden on the reservation, but the Chiricahuas had plenty of corn for brewing it, and drinking was one of the few pleasures of the old days that was left to them.

On the night of May 17, Geronimo, Mangas, Chihuahua, and old Nana got fairly well drunk on tiswin and decided to go to Mexico. They went to see Chato to invite him to go along, but Chato was sober and refused to join the party. He and Geronimo had a bitter quarrel, which very nearly ended in violence before Geronimo and the others departed. In the group were ninety-two women and children, eight boys, and thirty-four men. As they left San Carlos, Geronimo cut the telegraph wire.

Many reasons were given by both white men and Apaches for this sudden exodus from a reservation where everything apparently had been running smoothly. Some said it was because of the tiswin spree; others said that the bad stories going around about the Chiricahuas made them fearful of being arrested. “Having been placed in irons once before when the band was shipped to San Carlos,” Jason Betzinez said, “some of the leaders determined not to undergo such treatment again.”