Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (55 page)

Read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee Online

Authors: Dee Brown

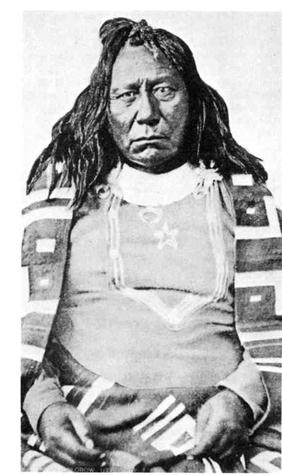

38. Quinkent, or Douglas. Courtesy of State Historical Society of Colorado.

Riding ahead of the column, Colorow arrived at his camp about nine o’clock on the morning of the twenty-ninth. He found his people very much excited over the approach of the soldiers. “I saw several start out in the direction toward the road where the soldiers were,” he said. “Afterward I left also and came up to where the first ones who went out had gathered.” There he met Jack and about sixty of his warriors. The two chiefs exchanged information, Jack telling Colorow about his unsatisfactory meeting with Meeker, and Colorow telling Jack that Major Thornburgh had promised to halt his soldiers at Milk River. “I then told Jack I thought it would be well for him to advise the young men not to make any warlike demonstrations at all, and he said it would be better to move them a piece off from the road. As yet we saw no soldiers from where we were, and we retired some distance from the road. Jack then said that when the soldiers should have arrived at Milk River [the line of the reservation] he would go down and see them.”

20

Neither Colorow nor Jack knew that Thornburgh’s column had already passed Milk River. After watering his horses there, Thornburgh decided to send the wagons along the canyon road with one escort troop while he took the remainder of the cavalry over a more direct route across a high ridge. By an irony of chance this would bring them directly upon the angry Utes that Jack had drawn away from the road in order to avoid any possible encounter.

About this time, a young Ute who had gone ahead to reconnoiter came galloping back. “The troops are not stopping where they promised to stop yesterday, but are coming on,” he told Jack.

Very much concerned now, Jack started up the ridge with his small band of warriors. In a few minutes he could see the soldiers’ wagons strung out along the road that twisted through the sagebrush toward the canyon. “I stood up on the hill with twenty or thirty of my men, and all at once I saw thirty or

forty soldiers in my front, and just as soon as they saw me they deployed off one after another. I was with General Crook the year before, fighting the Sioux, and I knew in a minute that as soon as this officer deployed his men out in that way it meant fight; so I told my men to deploy also.”

39. Colorow. Possibly a William H. Jackson photograph. Courtesy of State Historical Society of Colorado.

The officer commanding the advance cavalry troop was Lieutenant Samuel Cherry. After ordering his men to deploy, Cherry halted them at the base of the ridge and waited for Major Thornburgh to come forward. Thornburgh rode out a few yards and waved his hat to the Indians watching from the ridge. Several waved back.

For four or five minutes Jack waited for one of the officers to signal for a council, but they held their positions as though expecting the Utes to make the first move. “Then,” Jack said afterward, “I and another Indian went out to meet them.” Lieutenant Cherry dismounted and started walking toward the Utes. After taking a few steps, he waved his hat. A second later a single rifle shot broke the silence. “While we were still some distance apart, between the skirmish lines,” Jack said, “a shot was fired. I don’t know from which side, and in a second so many shots were fired, that I knew I could not stop the fight, although I swung my hat to my men and shouted, ‘Don’t fire; we only want to talk’; but they understood me to be encouraging them to fight.”

21

While the fighting grew in intensity, spreading to the wagon train, which went into a corral defense, news of the encounter reached Quinkent (Douglas) on the agency. He immediately went to “Nick” Meeker’s office and told him that soldiers had come inside the reservation. Douglas was sure the Ute warriors would fight them. Meeker replied that he did not believe there would be any trouble, and then he asked Douglas to go with him the following morning to meet the soldiers.

By early afternoon all the Utes at White River had heard that the soldiers were fighting their people at Milk River. About a dozen of them took their rifles and went out among the agency buildings shooting at every white workman in sight. Before the day ended they killed Nathan Meeker and all his white male employees. They made captives of the three white women, and

then fled toward an old Ute camp on Piceance Creek. Along the way each of the three white women was raped.

For almost a week the fighting continued at Milk River, with three hundred Ute warriors virtually surrounding the two hundred soldiers. Major Thornburgh was killed in the first skirmishing. When the fighting ended, his column had lost twelve killed, forty-three wounded. Thirty-seven Utes died in what they believed was a desperate stand to save their reservation from military seizure and to keep themselves from being taken as prisoners to Indian Territory.

At the Los Pinos agency, 150 miles to the south, Chief Ouray heard of the fighting with dismay. He knew that only immediate action could save his chieftainship and the entire Ute reservation. He dispatched a message by runner on October 2:

To the chief captains, headmen, and Utes at the White River agency:

You are hereby requested and commanded to cease hostilities against the whites, injuring no innocent persons or any others farther than to protect your own lives and property from unlawful and unauthorized combinations of horse thieves and desperados, as anything farther will ultimately end in disaster to all parties.

22

Ouray’s message and the arrival of cavalry reinforcements ended the fighting, but it was already too late to save the Utes from disaster. Governor Pitkin and William Vickers had been flooding Colorado with wild atrocity stories, many of them aimed at the innocent Uncompahgres at Los Pinos, most of whom were going peacefully about their business with no knowledge of what was happening at White River. Vickers called upon the white citizens of Colorado to rise up and “wipe out the red devils,” inspiring the frantic organization of militia units in towns and villages across the state. So many newspaper reporters arrived from the East to report this exciting new “Indian War” that Governor Pitkin decided to give them a special statement for publication:

“I think the conclusion of this affair will end the depredations in Colorado. It will be impossible for the Indians and whites to

live in peace hereafter. This attack had no provocation and the whites now understand that they are liable to be attacked in any part of the state where the Indians happen to be in sufficient force.

“My idea is that, unless removed by the government, they must necessarily be exterminated. I could raise 25,000 men to protect the settlers in twenty-four hours. The state would be willing to settle the Indian trouble at its own expense. The advantages that would accrue from the throwing open of 12,000,000 acres of land to miners and settlers would more than compensate all the expenses incurred.”

23

The White River Utes surrendered their three women captives, and then the inevitable investigating commission was formed to sift the causes, fix the blame, and set the punishments. The fight at Milk River was called an ambush, which it was not, and the affair at White River agency was called a massacre, which it was. Jack and Colorow and their followers were eventually excused from punishment on the grounds that they were warriors engaged in a fair fight. Douglas and the men at the agency were judged as murderers, but there was no one who could identify the Utes who had fired the shots that killed Nathan Meeker and his employees.

Douglas testified that he was in the agency storeroom when he heard the first gunshot. “I left the storeroom and went out a little way. Then I went to my house directly from where I was. When I started and got to my house it made me cry to think into what a state my friends had fallen.”

24

But because Arvilla Meeker swore in secret hearings that Douglas had forced sexual union with her, the sixty-year-old chief was sent off to Leavenworth prison. He was not charged with or tried for any crime; a public accusation of rape would have caused embarrassment to Mrs. Meeker, and in that age of sexual reticence, the fact that the act involved an Indian made it doubly abhorrent.

Individual punishments, however, were of little interest to the miners and politicians. They wanted to punish the entire seven nations of Utes, to push them off those twelve million acres of land waiting to be dug up, dammed up, and properly deforested so that fortunes could be made in the process.

Ouray was a dying man in 1880 when the Indian Bureau brought him to Washington to defend the future of his people. Ill with nephritis, he bowed to the wishes of Big Eyes Schurz and other officials who decided “the Utes must go” to a new reservation in Utah—on land the Mormons did not want. Ouray died before the Army herded his people together in August, 1881, for the 350-mile march out of Colorado into Utah. Except for a small strip of territory along the southwest corner—where a small band of Southern Utes was allowed to live—Colorado was swept clean of Indians. Cheyenne and Arapaho, Kiowa and Comanche, Jicarilla and Ute—they had all known its mountains and plains, but now no trace of them remained but their names on the white man’s land.

The Last of the Apache Chiefs

1880

—

June 1,

population of United States is 50,155,783.1881

—

March 4,

James A. Garfield inaugurated as President. March 13, in Russia, nihilists assassinate Czar Alexander. July 2, Garfield shot by assassin; dies September 19; Chester A. Arthur becomes President.1882

—

April 3,

Jesse James shot and killed at St. Joseph, Missouri. September 4, Edison switches on first commercial electric lights in New York Central Station. Mark Twain’s

Huckleberry Finn

published.1883

—

March 24,

first telephone connection between New York and Chicago. November 3, U.S. Supreme Court decides that an American Indian is by birth an alien and a dependent. Robert Louis Stevenson’s

Treasure Island

published.1884

—

January,

Russia abolishes poll tax, last relic of serfdom. March 13, in the Sudan, Siege of Khartoum begins.1885

—

January 26,

Khartoum falls to the Mahdi; Governor General Charles George Gordon killed. March 4, Grover Cleveland becomes first Democratic President since Civil War.1886

—

May 1,

general strikes spread across United States in demand for eight-hour day. May 4, anarchists bomb police in Haymarket Square, Chicago, killing seven, wounding sixty. October 28, Statue of Liberty erected on Bedloe’s Island. December 8, American Federation of Labor founded.I was living peacefully with my family, having plenty to eat, sleeping well, taking care of my people, and perfectly contented. I don’t know where those bad stories first came from. There we were doing well and my people well. I was behaving well. I hadn’t killed a horse or man, American or Indian. I don’t know what was the matter with the people in charge of us. They knew this to be so, and yet they said I was a bad man and the worst man there; but what had I done? I was living peacefully there with my family under the shade of the trees, doing just what General Crook had told me I must do and trying to follow his advice. I want to know now who it was ordered me to be arrested. I was praying to the light and to the darkness, to God and to the sun, to let me live quietly there with my family. I don’t know what the reason was that people should speak badly of me. Very often there are stories put in the newspapers that I am to be hanged. I don’t want that anymore. When a man tries to do right, such stories ought not to be put in the newspapers. There are very few of my men left now. They have done some bad things but I want them all rubbed out now and let us never speak of them again. There are very few of us left.

—

GOYATHLAY (GERONIMO)

A

FTER THE DEATH OF

Cochise in 1874, his oldest son, Taza, became chief of the Chiricahuas, and Taglito (Tom Jeffords) continued as agent on the Apache Pass reservation. Unlike his father, Taza was not able to secure the steadfast allegiance of all the Chiricahuas. Within a few months these Apaches were split into factions, and in spite of earnest efforts by both Taza and Jeffords, the raiding which Cochise had strictly forbidden was resumed. Because of the Chiricahua reservation’s proximity to Mexico, it became a way station and sanctuary for Apache raiding parties moving in and out of Arizona and Mexico. Land-hungry settlers, miners, and politicians wasted no

time in demanding removal of all Chiricahuas to some other location.

By 1875 the United States government’s Indian policy was turning toward concentration of tribes either in Indian Territory or on large regional reservations. White Mountain, with its 2.5 million acres in eastern Arizona, was larger than all the other Apache reservations in the Southwest combined. Its agency, San Carlos, was already the administration point for seven Apache bands, and when Washington officials began receiving reports of trouble on the Chiricahua reservation, they saw this as an excellent excuse to move the Chiricahuas to San Carlos.