Bully for Brontosaurus (53 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

Third, some natural populations may be so small that individuality dominates over pattern even if a larger system might fall under predictable law. If I am flipping a coin 10,000 times in a row, with nothing staked on any particular toss, then an individual flip neither has much effect in itself nor influences the final outcome to any marked degree. But if I am flipping one coin once to start a football game, then a great deal rides on the unpredictability of an individual event. Some important populations in nature are closer in number to the single toss than to the long sequence. Yet we cannot deny them entry into the domain of science.

Consider the large, orbiting objects of our solar system—nine planets and a few score moons. The domain of celestial mechanics has long been viewed as the primal realm of lawfulness and predictability in science—the bailiwick of Newton and Kepler, Copernicus and Galileo, inverse square laws and eclipses charted to the second. We used to view the objects themselves, planets and moons, in much the same light—as regular bodies formed under a few determining conditions. Know composition, size, distance from the sun, and most of the rest follows.

As I write this essay,

Voyager 2

has just left the vicinity of Neptune and ventured beyond the planetary realm of our solar system—its “grand tour” complete after twelve years and the most colossal Baedecker in history: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Scientists in charge have issued quite appropriate statements of humility, centered upon the surprises conveyed by stunning photographs of outer planets and their moons. I admit to the enormous mystery surrounding so many puzzling features—the whirling storms of Neptune, when the closer and larger Uranus appears so featureless; the diverse and complex terrain of Uranus’s innermost moon, Miranda (see the preceding essay). But I do think that a generality has emerged from this confusing jumble of diverse results, so many still defying interpretation—a unifying principle usually missed in public reports because it falls outside the scope of stereotypical science.

I offer, as the most important lesson from

Voyager

, the principle of individuality for moons and planets. This contention should elicit no call for despair or surrender of science to the domain of narrative. We anticipated greater regularity, but have learned that the surfaces of planets and moons cannot be predicted from a few general rules. To understand planetary surfaces, we must learn the particular history of each body as an individual object—the story of collisions and catastrophes, more than steady accumulations; in other words, its unpredictable single jolts more than daily operations under nature’s laws.

While

Voyager

recedes ever farther on its arc to the stars, we have made a conceptual full circle. When we launched

Voyager

in 1977, we mounted a copper disk on its side, with a stylus, cartridge, and instructions for playing. On this first celestial record, we placed the diversity of the earth’s people. We sent greetings in fifty-five languages, and even added some whale song for ecumenical breadth. This babble of individuality was supposed to encounter, at least within our solar system, a regular set of worlds shaped by a few predictable forces. But the planets and moons have now spoken back to

Voyager

with all the riotous diversity of that unplayed record. The solar system is a domain of individuality by my third argument for small populations composed of distinctive objects. And science—that wonderfully diverse enterprise with methods attuned to resolve both the lawful millions and the unitary movers and shakers—has been made all the richer.

This is my third and last essay on

Voyager

. The first, which shall be my eternal incubus, praised the limited and lawful regularity that

Voyager

would presumably discover on planetary surfaces throughout the solar system. I argued, following the standard “line” at the time (but bowing to convention is never a good excuse), that simple rules of size and composition would set planetary surfaces. With sufficient density of rocky composition, size alone should reign. Small bodies, with their high ratios of surface to volume, are cold and dead—for they lose so much internal heat through their relatively large surface and are too small to hold an atmosphere. Hence, they experience no internal forces of volcanism and plate tectonics and no external forces of atmospheric erosion. In consequence, small planets and moons should be pristine worlds studded with ancient impact craters neither eroded nor recycled during billions of years. Large bodies, on the other hand, maintain atmospheres and internal heat machines. Their early craters should be obliterated, and their surfaces, like our earth’s, should bear the marks of continuous, gentler action.

The first data from planetary probes followed these expectations splendidly. Small Mercury and smaller Phobos and Deimos (the moons of Mars) are intensely cratered, while Mars, at its intermediary size, showed a lovely mixture of ancient craters and regions more recently shaped by erosion and volcanic action. But then

Voyager

reached Jupiter and the story started to unravel in favor of individuality granted by distinctive histories for each object.

Io, Jupiter’s innermost major moon, should have been dead and cratered at its size, but

Voyager

spotted large volcanoes spewing forth plumes of sulfur instead. Saturn’s amazingly complex rings told a story of repeated collisions and dismemberments. Miranda, innermost moon of Uranus, delivered the

coup de grâce

to a dying theory. Miranda should be yet another placid body, taking its lumps in the form of craters and wearing the scars forever. Instead,

Voyager

photographed more signs of varied activity than any other body had displayed—a geological potpourri of features, suggesting that Miranda had been broken apart and reaggregated, perhaps more than once. Brave new world indeed.

I threw in the towel and wrote my second essay in the

mea culpa

mode (reprinted as the preceding essay). Now I cement my conversion.

Voyager

has just passed Neptune, last post of the grand tour, and fired a glorious parting shot for individuality. We knew that Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, was odd in one important sense. All other bodies, planets around the sun and moons around the planets, revolve in the same direction—counterclockwise as you look down upon the plane of the solar system from above.

*

But Triton moves around Neptune in a clockwise direction. Still, at a size smaller than our moon, it should have been another of those dead and cratered worlds now mocked by the actual diversity of our solar system. Triton—and what a finale—is, if anything, even more diverse, active, and interesting than Miranda.

Voyager

photographed some craters, but also a complexly cracked and crumpled surface and, most unexpectedly of all, volcanoes, probably spewing forth nitrogen in streaks over the surface of Triton.

In short, too few bodies, too many possible histories. The planets and moons are not a repetitive suite, formed under a few simple laws of nature. They are individual bodies with complex histories. And their major features are set by unique events—mostly catastrophic—that shape their surfaces as Passion decimated the Gombe chimps or the austral hound wreaked havoc on the kiwis of Waitangi. Planets are like organisms, not water molecules; they have irreducible personalities built by history. They are objects in the domain of a grand enterprise—natural history—that unites both styles of science in its ancient and still felicitous name.

As

Voyager

has increased our knowledge, and at least for this paleontologist, integrated his two childhood loves of astronomy and fossils on the common ground of natural history, I cannot let this primary scientific triumph of our generation pass from our solar system (and these essays) without an additional comment in parting.

Knowledge and wonder are the dyad of our worthy lives as intellectual beings.

Voyager

did wonders for our knowledge, but performed just as mightily in the service of wonder—and the two elements are complementary, not independent or opposed. The thought fills me with awe—a mechanical contraption that could fit in the back of a pickup truck, traveling through space for twelve years, dodging around four giant bodies and their associated moons, and finally sending exquisite photos across more than four light-hours of space from the farthest planet in our solar system. (Pluto, although usually beyond Neptune, rides a highly eccentric orbit about the sun. It is now, and will be until 1999, within the orbit of Neptune and will not regain its status as outermost until the millennium. The point may seem a bit forced, but symbols matter and Neptune is now most distant. Moments and individualities count.)

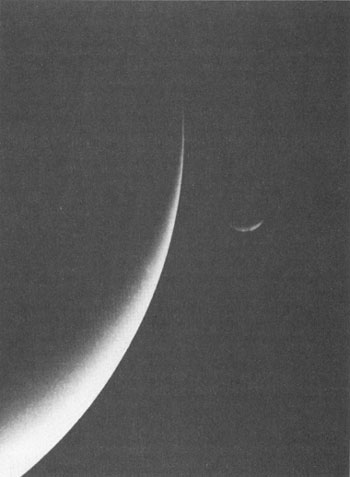

The photos fill me with joy for their fierce beauty. To see the most distant moon with the detailed clarity of an object shot at ten palpable paces; the abstract swirling colors in Jupiter’s great spot; the luminosity and order of Saturn’s rings; the giant ripple-crater of Callisto, the cracks of Ganymede, the sulfur basins of Io, the craters of Mimas, the volcanoes of Triton. As

Voyager

passed Neptune, her programmers made a courtly and proper bow to aesthetics and took the most gorgeous picture of all, for beauty’s sake—a photograph of Neptune as a large crescent, with Triton as a smaller crescent at its side. Two horns, proudly independent but locked in a common system. Future advertisers and poster makers may turn this exquisite object into a commercial cliché, but let it stand for now as a symbol for the fusion of knowledge and wonder.

Voyager

has also served us well in literary allusions. Miranda is truly the “brave new world” of her most famous line. And Triton conjures all the glory and meaning of his most celebrated reference. You may have suppressed it, for forced memorization was a chore, but “The World Is Too Much with Us” remains a great poem (still assigned, I trust, by teachers). No one has ever matched Wordsworth in describing the wonder of childhood’s enthusiasms—a wonder that we must strive to maintain through life’s diminution of splendor in the grass and glory in the flower, for we are lost eternally when this light dies. So get to know Triton in his planetary form, but also remember him as Wordsworth’s invocation to perpetual wonder:

…Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn.

The most elegant photograph of the

Voyager

mission—a symbol of both knowledge and wonder. The horns (crescents) of Neptune and Triton.

PHOTO COURTESY NASA/J.P.L.

Altholz, Josef L. 1980. The Huxley-Wilberforce debate revisited.

Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Science

, 35(3):313–316.

Baker, Jeffrey J.W., and Garland E. Allen. 1982.

The study of biology

. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Barbour, T., and J.C. Phillips. 1911. Concealing coloration again.

The Auk

, 28(2):179–187.

Bates, Henry Walter. 1863. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon Valley.

Transactions of the Linnaean Society

.

Bates, Henry Walter. 1876.

The naturalist on the river Amazons: A record of adventures, habits of animals, sketches of Brazilian and Indian life, and aspects of Nature under the equator, during eleven years of travel

. London: J. Murray.

Berman, D.S., and J.S. McIntosh. 1978. Skull and relationships of the Upper Jurassic sauropod

Apatosaurus. Bulletin of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History

, No. 8.

Bierer, L.K., V.F. Liem, and E.P. Silberstein. 1987.

Life Science

. Heath.

Bligh, W. 1792.

A voyage to the South Sea undertaken by command of his Majesty for the purpose of conveying the bread-fruit tree to the West Indies in his Majesty’s ship the

Bounty,

commanded by Lt. W. Bligh, including an account of the mutiny on board the said ship

. London.

Bohringer, R.C. 1981. Cutaneous receptors in the bill of the platypus (

Ornithorhyncus anatinus

).

Australian Mammalogy

4:93–105.

Bohringer, R.C., and M.J. Rowe. 1977. The organization of the sensory and motor areas of cerebral cortex in the platypus

Ornithorhynchus anatinus. Journal of Comparative Neurology

, 174(1): 1–14.

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1979.

The book of sand

. London: A. Lane.

Brody, Samuel. 1945.

Bioenergetics and growth: with special reference to the efficiency complex in domestic animals

. New York: Hefner.

Browne, Janet. 1978. The Charles Darwin—Joseph Hooker correspondence: An analysis of manuscript resources and their use in biography.

Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History

, 8:351–366.

Brownlie, A.D., and M.F. Lloyd Prichard. 1963. Professor Fleeming Jenkin, 1833–1885 pioneer in engineering and political economy.

Oxford Economic Papers

, NS, 15(3):204–216.

Burnet, Thomas. 1691.

Sacred theory of the earth

. London: R. Norton.

Burrell, Harry. 1927.

The platypus: Its discovery, position, form and characteristics, habits and life history

. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Bury, J.B. 1920.

The idea of progress: An inquiry into its origin and growth

. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd.

Busse, K. 1970. Care of the young by male

Rhinodrma darwini. Copeia

, No. 2, p. 395.

Calder, A., III. 1978. The kiwi.

Scientific American

, July.

Calder, Wm. A., III. 1979. The kiwi and egg design: Evolution as a package deal.

Bioscience

, 29(8):461–467.

Calder, A., III. 1984.

Size, function and life history

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Caldwell, W.H. 1888. The embryology of Monotremata and Marsupialia. Part I.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London

(B), 178:463–483.

Camper, Petrus. 1791.

Physical dissertation on the real differences that men of different countries and ages display in their facial traits; on the beauty that characterizes the statues and engraved stones of antiquity; followed by the proposition of a new method for drawing human heads with the greatest accuracy

. Utrecht: B. Wild & J. Altheer.

Cavalli-Sforza, L.L., A. Piazza, P. Mendozzi, and J. Mountain. 1988. Reconstruction of human evolution: Bringing together genetic, archaeological, and linguistic data.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

, August, pp. 6002–6006.

Chamberlin, T.C., and R. Salisbury. 1909.

College Geology

(American Science Series). New York: Henry Holt & Co.

Chambers, Robert. 1844.

Vestiges of the natural history of creation

. London: J. Churchill.

Chapman, Frank M. 1933.

Autobiography of a bird lover

. New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., Inc.

Coletta, Paolo E. 1969.

William Jennings Bryan:

Vol. 3,

Political Puritan

. University of Nebraska Press.

Cope, E.D. 1874.

The origin of the fittest, and the primary factors of organic evolution

. New York: Arno Press.

Corben, C.J., G.J. Ingram, and M.J. Tyler. 1974. Gastric brooding: Unique form of parental care in an Australian frog.

Science

, 186:946.

Cott, Hugh B. 1940.

Adaptive coloration in animals

. London: Methuen.

Crosland, M.J., and Ross H. Crozier. 1986.

Myrmecia pilosula

, an ant with only one pair of chromosomes.

Science

, 231:1278.

Darnton, Robert. 1968.

Mesmerism and the end of the Enlightenment in France

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Darwin, Charles. 1859.

On the origin of species by means of natural selection

. London: John Murray.

Darwin, Charles. 1863. Review of Bates’s paper.

Natural History Reviews

, pp. 219–224.

Darwin, Charles. 1868.

Variation of animals and plants under domestication

. London: John Murray.

Darwin, Erasmus. 1794.

Zoonomia, or the laws of organic life

. London: J.Johnson.

Darwin, Francis. 1887.

The life and letters of Charles Darwin

. London: John Murray.

David, Paul A. 1986. Understanding the economics of QWERTY: The necessity of history. In W.N. Parker, ed.,

Economic history and the modern economist

, pp. 30–49. New York: Basil Blackwell, Inc.

Davis, D.D. 1964. Monograph on the giant panda. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

De Quatrefages, A. 1864.

Metamorphoses of man and the lower animals

. London: Robert Hardwicke, 192 Piccadilly.

Disraeli, Benjamin. 1880.

Endymion

.

Douglas, Matthew M. 1981. Thermoregulatory significance of thoracic lobes in the evolution of insect wings.

Science

, 211:84–86.

Dyson, Freeman. 1981.

Disturbing the universe

. New York: Harper & Row.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. 1975.

Krieg und Frieden aus der Sicht der Verhaltens-forschung

. Munchen, Zurich: Piper.

Eldredge, N., and S.J. Gould. 1972. Punctuated equilibria: An alternative to phyletic gradualism. In T.J.M. Schopf, ed.,

Models in paleobiology

, pp. 82–115. San Francisco: Freeman, Cooper and Co.

Erasmus, Desiderius. 1508.

Adagia

.

Flower, J.W. 1964. On the origin of flight in insects.

Journal of Insect Physiology

, 10:81–88.

Force, James. 1985.

William Whiston, honest Newtonian

. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Freud, Sigmund. 1905–1915. Three essays on the theory of sexuality.

Gates, Richard G. 1978. Vision in the monotreme Echidna (

Tachyglossus aculeatus

).

Australian Zoologist

, 20(1):147–169.

Gilley, Sheridan. 1981. The Huxley-Wilberforce debate: A reconsideration. In K. Robbins, ed.,

Religion and humanism

, Vol. 17, pp. 325–340.

Gilovich, T., R. Vallone, and A. Tversky. 1985. The hot hand in basketball: On the misperception of random sequences.

Cognitive Psychology

, 17:295–314.

Gladstone, W.E. 1858.

Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age

.

Gladstone, W.E. 1885. Dawn of creation and of worship.

The Nineteenth Century

, November.

Goldschmidt, R. 1940 (reprinted 1982 with introduction by S.J. Gould).

The material basis of evolution

. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Goldschmidt, R. 1948. Glowworms and evolution.

Révue Scientifique

, 86:607–612.

Goodall, Jane. 1986.

The chimpanzees of Gombe

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gould, S.J. 1975. On the scaling of tooth size in mammals.

American Zoologist

, 15:351–362.

Gould, S.J. 1977.

Ontogeny and phylogeny

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gould, S.J. 1980.

The panda’s thumb

. New York: W.W. Norton.

Gould, S.J. 1981.

The mismeasure of man

. New York: W.W. Norton.

Gould, S.J. 1985.

The flamingo’s smile

. New York: W.W. Norton.

Gould, S.J. 1985. Geoffroy and the homeobox.

Natural History

, November, pp. 22–23.

Gould, S.J. 1987. Bushes all the way down.

Natural History

, June, pp. 12–19.

Gould, S.J. 1987.

Time’s arrow, time’s cycle

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gould, S.J. 1989. Winning and losing: It’s all in the game.

Rotunda

, Spring 1989, pp. 25–33.

Gould, S.J., and Elisabeth S. Vrba. 1982. Exaptation—a missing term in the science of form.

Paleobiology

, 8(1):4–15.

Grant, Tom. 1984.

The Platypus

. New South Wales University Press.

Grant, Verne. 1963.

The origin of adaptations

. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gregory, William King. 1927.

Hesperopithecus

apparently not an ape nor a man.

Science

, 66:579–587.

Gregory, William King, and Milo Hellman. 1923. Notes on the type of

Hesperopithecus haroldcookii

Osborn. American Museum of Natural History

Novitates

, 53:1–16.

Gregory, William King, and Milo Hellman. 1923. Further notes on the molars of

Hesperopithecus

and of

Pithecanthropus. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History

, Vol. 48, Art. 13, pp. 509–526.

Griffiths, M. 1968.

Echidnas

. New York: Pergamon Press.

Griffiths, M. 1978.

The biology of monotremes

. San Diego/Orlando: Academic Press.

Haller, John S. 1971.

Outcasts from evolution

. University of Illinois Press.

Hegner, Robert W. 1912.

College zoology

. New York: Macmillan Co.

Heinrich, B. 1981.

Insect thermoregulation

. San Diego/Orlando: Academic Press.

Hite, Shere. 1976.

The Hite Report: A nationwide report on sexuality

. New York: Macmillan.

Holway, John. 1987. A little help from his friends.

Sports Heritage

, November/December.

Home, Everard. 1802. A description of the anatomy of the

Ornithorhynchus paradoxus. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

, Part 1, No. 4, pp. 67–84.

Howes, G.B. 1888. Notes on the gular brood-pouch of

Rhinoderma darwini. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London

, pp. 231–237.

Hrdy, Sarah. 1981.

The women that never evolved

. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hunter, George William. 1914.

A civic biology

. New York: American Book Company.

Hutton, J. 1788. Theory of the Earth.

Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

, 1:209–305.

Hutton, J. 1795.

The theory of the Earth

. Edinburgh: William Creech.

Huxley, Julian. 1927. On the relation between egg-weight and body-weight in birds.

Journal of the Linnaean Society of London

, 36:457–466.

Huxley, Leonard. 1906.

Life and letters of Thomas H. Huxley

. New York: Appleton.

Huxley, T. H. 1880. On the application of the laws of evolution to the arrangement of the Vertebrata, and more particularly of the Mammalia.

Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London

, No. 43, pp. 649–661.

Huxley, T. H. 1885. The interpreters of Genesis and the interpreters of Nature.

The Nineteenth Century

, December.

Huxley, T. H. 1888. The struggle for existence in human society.

The Nineteenth Century

, February.

Huxley, T. H. 1896.

Science and education

. New York: Appleton & Co.

Huxley, T. H. 1896. Mr. Gladstone and Genesis.

The Nineteenth Century

.

Huxley, T.H., and Julian Huxley. 1947.

Evolution and ethics

. London: Pilot Press.

Ingersoll, Ernest. 1906.

The life of animals

. New York: Macmillan.

Ingram, G.J., M. Anstis, and C.J. Corben. 1975. Observations on the Australian leptodactylid frog,

Assa darlingtoni. Herpetologia

, 31:425–429.

Jackson, J.F. 1974. Goldschmidt’s dilemma resolved: Notes on the larval behavior of a new neotropical web-spinning Mycetophilid (Diptera).

American Midland Naturalist

, 92(1):240–245.

James, William. 1909. Letter quoted in

The autobiography of Nathaniel Southgate Shaler

. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Jenkin, F. 1867. Darwin and the origin of species.

North British Review

, June.

Jerison, H.J. 1973.

Evolution of the brain and intelligence

. San Diego/Orlando: Academic Press.

Jordan, David Starr, and Vernon L. Kellogg. 1900.

Animal life: A first book of zoology

. New York: D. Appleton & Co.

Kellogg, Vernon L. 1907.

Darwinism to-day

. London: G. Bell & Sons.

Kellogg, Vernon L. 1917.

Headquarters nights

. Boston.

Keyes, Ralph. 1980.

The height of your life

. Boston: Little, Brown.