Bully for Brontosaurus (17 page)

Read Bully for Brontosaurus Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

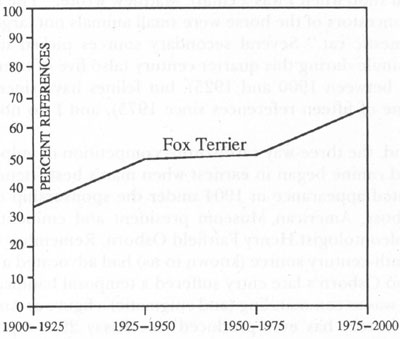

The rise to dominance of fox terriers as similes for the size of the earliest horses. Top graph: Increasing domination of dogs over foxes through time. Lower graph: Increase in percentage of fox terrier references among sources citing dogs as their simile.

IROMIE WEERAMANTRY. COURTESY OF

NATURAL HISTORY

.

Throughout the nineteenth century all sources that we have found (eight references, including such major figures as Joseph Le Conte, Archibald Geikie, and even Marsh’s bitter enemy E. D. Cope) copy Marsh’s favored simile—they all describe

Eohippus

as fox-sized. We are confident that Marsh’s original description is the source because most references also repeat his statement that

Miohippus

is the size of a sheep. How, then, did fox terriers replace their prey?

The first decade of our century ushered in a mighty Darwinian competition among three alternatives and led to the final triumph of fox terriers. By 1910, three similes were battling for survival. Marsh’s original fox suffered greatly from competition, but managed to retain a share of the market at about 25 percent (five of twenty citations between 1900 and 1925 in our sample)—a frequency that has been maintained ever since (see accompanying figure). Competition came from two stiff sources, however—both from the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

First, in 1903, W. D. Matthew, vertebrate paleontologist at the Museum, published his famous pamphlet

The Evolution of the Horse

(it remained in print for fifty years, and was still being sold at the Museum shop when I was a child). Matthew wrote: “The earliest known ancestors of the horse were small animals not larger than the domestic cat.” Several secondary sources picked up Matthew’s simile during this quarter century (also five of twenty references between 1900 and 1925), but felines have since faded (only one of fifteen references since 1975), and I do not know why.

Second, the three-way carnivorous competition of vulpine, feline, and canine began in earnest when man’s best friend made his belated appearance in 1904 under the sponsorship of Matthew’s boss, American Museum president and eminent vertebrate paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn. Remember that no nineteenth-century source (known to us) had advocated a canine simile, so Osborn’s late entry suffered a temporal handicap. But Osborn was as commanding (and enigmatic) a figure as American natural history has ever produced (see Essay 29)—a powerful patrician in science and politics, imperious but kind, prolific and pompous, crusader for natural history and for other causes of opposite merit (Osborn wrote, for example, a glowing preface to the most influential tract of American scientific racism,

The Passing of the Great Race

, by his friend Madison Grant).

In the

Century Magazine

for November 1904, Osborn published a popular article, “The Evolution of the Horse in America.” (Given Osborn’s almost obsessively prolific spate of publications, we would not be surprised if we have missed an earlier citation.) His first statement about

Eohippus

introduces the comparison that would later win the competition:

We may imagine the earliest herds of horses in the Lower Eocene (

Eohippus

, or “dawn horse” stage) as resembling a lot of small fox-terriers in size…. As in the terrier, the wrist (knee) was near the ground, the hand was still short, terminating in four hoofs, with a part of the fifth toe (thumb) dangling at the side.

Osborn provides no rationale for his choice of breeds. Perhaps he simply carried Marsh’s old fox comparison unconsciously in his head and chose the dog most similar in name to the former standard. Perhaps Roger Angell’s conjecture is correct. Osborn certainly came from a social set that knew about fox hunting. Moreover, as the quotation indicates, Osborn extended the similarity of

Eohippus

and fox terrier beyond mere size to other horselike attributes of this canine breed (although, in other sources, Osborn treated the whippet as even more horselike, and even mounted a whippet’s skeleton for an explicit comparison with

Eohippus

). Roger Angell described his fox terrier to me: “The back is long and straight, the tail is held jauntily upward like a trotter’s, the nose is elongated and equine, and the forelegs are strikingly thin and straight. In motion, the dog comes down on these forelegs in a rapid and distinctive, stiff, flashy style, and the dog appears to walk on his tiptoes—on hooves, that is.”

In any case, we can trace the steady rise to domination of dog similes in general, and fox terriers in particular, ever since. Dogs reached nearly 50 percent of citations (nine of twenty) between 1900 and 1925, but have now risen to 60 percent (nine of fifteen) since 1975. Meanwhile, the percentage of fox terrier citations among dog similes had also climbed steadily, from one-third (three of nine) between 1900 and 1925 to one-half (eight of sixteen) between 1925 and 1975, to two-thirds (six of nine) since 1975. Osborn’s simile has been victorious.

Copying is the only credible source for these shifts of popularity—first from experts; then from other secondary sources. Shifts in fashion cannot be recording independent insights based on observation of specimens.

Eohippus

could not, by itself, say “fox” to every nineteenth-century observer and “dog” to most twentieth-century writers. Nor can I believe that two-thirds of all doginclined modern writers would independently say, “Aha, fox terrier” when contemplating the dawn horse. The breed is no longer so popular, and I suspect that most writers, like me, have only the vaguest impression about fox terriers when they copy the venerable simile.

In fact, we can trace the rise to dominance of fox terriers in our references. The first post-Osborn citation that we can find (Ernest Ingersoll,

The Life of Animals

, MacMillan, 1906) credits Osborn explicitly as author of the comparison with fox terriers. Thereafter, no one cites the original, and I assume that the process of text copying text had begun.

Two processes combined to secure the domination of fox terriers. First, experts began to line up behind Osborn’s choice. The great vertebrate paleontologist W. B. Scott, for example, stood in loyal opposition in 1913, 1919, and 1929 when he cited both alternatives of fox and cat. But by 1937, he had switched: “

Hyracotherium

was a little animal about the size of a fox-terrier, but horse-like in all parts.” Second, dogs became firmly ensconced in major textbooks. Both leading American geology textbooks of the early twentieth century (Chamberlin and Salisbury, 1909 edition, and Pirsson and Schuchert, 1924 edition) opt for canines, as does Hegner’s zoology text (1912) and W. Maxwell Read’s fine children’s book (a mainstay of my youth)

The Earth for Sam

(1930 edition).

Fox terriers have only firmed up their position ever since. Experts cite this simile, as in A. S. Romer’s leading text,

Vertebrate Paleontology

(3d edition, 1966): “‘

Eohippus

’ was a small form, some specimens no larger than a fox terrier.” They have also entered the two leading high-school texts: (1) Otto and Towle (descendant of Moon, Mann, and Otto, the dominant text for most of the past fifty years): “This horse is called

Eohippus

. It had four toes and was about the size of a fox-terrier” (1977 edition); (2) the

Biological Sciences Curriculum Study, Blue Edition

(1968): “The fossil of a small four-toed animal about the size of a fox-terrier was found preserved in layers of rock.” College texts also comply. W. T. Keeton, in his

Biological Science

, the Hertz of the profession, writes (1980 edition): “It was a small animal, only about the size of a fox-terrier.” Baker and Allen’s

The Study of Biology

, a strong Avis, agrees (1982 edition): “This small animal

Eohippus

was not much bigger than a fox-terrier.”

You may care little for dawn horses or fox terriers and might feel that I have made much of nothing in this essay. But I cite the case of the creeping fox terrier clone not for itself, but rather as a particularly clear example of a pervasive and serious disease—the debasement of our textbooks, the basic tool of written education, by endless, thoughtless copying.

My younger son started high school last month. For a biology text, he is using the 4th edition of

Biology: Living Systems

, by R. F. Oram, with consultants P. J. Hummer and R. C. Smoot (Charles E. Merrill, 1983, but listed on the title page, following our modern reality of conglomeration, as a Bell and Howell Company). I was sad and angered to find several disgraceful passages of capitulation to creationist pressure. Page one of the chapter on evolution proclaims in a blue sidebar: “The theory of evolution is the most widely accepted scientific explanation of the origin of life and changes in living things. You may wish to investigate other theories.” Similar invitations are not issued for any other well-established theory. Students are not told that “most folks accept gravitation, but you might want to check out levitation” or that “most people view the earth as a sphere, but you might want to consider the possibility of a plane.” When the text reaches human history, it doesn’t even grant majority status to our evolutionary consensus: “Humans are indeed unique, but because they are also organisms, many scientists believe that humans have an evolutionary history.”

Yet, as I argued at the outset, I find these compromises to outside pressure, disgraceful though they be, less serious than the internal disease of cloning from text to text. There is virtually only one chapter on evolution in all high-school biology texts, copied and degraded, then copied and degraded again. My son’s book is no exception. This chapter begins with a discussion of Lamarck and the inheritance of acquired characters. It then moves to Darwin and natural selection and follows this basic contrast with a picture of a giraffe and a disquisition of Lamarckian and Darwinian explanations for long necks. A bit later, we reach industrial melanism in moths and dawn horses of you-know-what size.

What is the point of all this? I could understand this development if Lamarckism were a folk notion that must be dispelled before introducing Darwin, or if Lamarck were a household name. But I will lay 100 to 1 that few high-school students have ever heard of Lamarck. Why begin teaching evolution by explicating a false theory that is causing no confusion? False notions are often wonderful tools in pedagogy, but not when they are unknown, are provoking no trouble, and make the grasp of an accepted theory more difficult. I would not teach more sophisticated college students this way; I simply can’t believe that this sequence works in high school. I can only conclude that someone once wrote the material this way for a reason lost in the mists of time, and that authors of textbooks have been dutifully copying “Lamarck…Darwin…giraffe necks” ever since.

(The giraffe necks, by the way, make even less sense. This venerable example rests upon no data at all for the superiority of Darwinian explanation. Lamarck offered no evidence for his interpretation and only introduced the case in a few lines of speculation. We have no proof that the long neck evolved by natural selection for eating leaves at the tops of acacia trees. We only prefer this explanation because it matches current orthodoxy. Giraffes do munch the topmost leaves, and this habit obviously helps them to thrive, but who knows how or why their necks elongated? They may have lengthened for other reasons and then been fortuitously suited for acacia leaves.)

If textbook cloning represented the discovery of a true educational optimum, and its further honing and propagation, then I would not object. But all evidence—from my little story of fox terriers to the larger issue of a senseless but nearly universal sequence of Lamarck, Darwin, and giraffe necks—indicates that cloning bears an opposite and discouraging message. It is the easy way out, a substitute for thinking and striving to improve. Somehow I must believe—for it is essential to my notion of scholarship—that good teaching requires fresh thought and genuine excitement, and that rote copying can only indicate boredom and slipshod practice. A carelessly cloned work will not excite students, however pretty the pictures. As an antidote, we need only the most basic virtue of integrity—not only the usual, figurative meaning of honorable practice but the less familiar, literal definition of wholeness. We will not have great texts if authors cannot shape content but must serve a commercial master as one cog in an ultimately powerless consortium with other packagers.

To end with a simpler point amid all this tendentiousness and generality: Thoughtlessly cloned “eternal verities” are often false. The latest estimate I have seen for the body size of

Hyracotherium

(MacFadden, 1986), challenging previous reconstructions congenial with the standard simile of much smaller fox-terriers, cites a weight of some twenty-five kilograms, or fifty-five pounds.

Lassie come home!

I STILL DON’T UNDERSTAND

why a raven is like a writing desk, but I do know what binds Hernando Cortés and Thomas Henry Huxley together.

On February 18, 1519, Cortés set sail for Mexico with about 600 men and, perhaps more important, 16 horses. Two years later, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán lay in ruins, and one of the world’s great civilizations had perished.

Cortés’s victory has always seemed puzzling, even to historians of an earlier age who did not doubt the intrinsic superiority of Spanish blood and Christian convictions. William H. Prescott, master of this tradition, continually emphasizes Cortés’s diplomatic skill in making alliances to divide and conquer—and his good fortune in despoiling Mexico during a period of marked internal dissension among the Aztecs and their vassals. (Prescott published his

History of the Conquest of Mexico

in 1843; it remains among the most exciting and literate books ever written.)

Prescott also recognized Cortés’s two “obvious advantages on the score of weapons”—one inanimate and one animate. A gun is formidable enough against an obsidian blade, but consider the additional impact of surprise when your opponent has never seen a firearm. Cortés’s cavalry, a mere handful of horses and their riders, caused even more terror and despair, for the Aztecs, as Prescott wrote,

had no large domesticated animals, and were unacquainted with any beast of burden. Their imaginations were bewildered when they beheld the strange apparition of the horse and his rider moving in unison and obedient to one impulse, as if possessed of a common nature; and as they saw the terrible animal, with “his neck clothed in thunder,” bearing down their squadrons and trampling them in the dust, no wonder they should have regarded him with the mysterious terror felt for a supernatural being.

On the same date, February 18, in 1870, Thomas Henry Huxley gave his annual address as president of the Geological Society of London and staked his celebrated claim that Darwin’s ideal evidence for evolution had finally been uncovered in the fossil record of horses—a sequence of continuous transformation, properly arrayed in temporal order:

It is easy to accumulate probabilities—hard to make out some particular case, in such a way that it will stand rigorous criticism. After much search, however, I think that such a case is to be made out in favor of the pedigree of horses.

Huxley delineated the famous trends to fewer toes and higher-crowned teeth that we all recognize in this enduring classic among evolutionary case histories. Huxley viewed this lineage as a European affair, proceeding from fully three-toed

Anchitherium

, to

Hipparion

with side toes “reduced to mere dew-claws [that] do not touch the ground,” to modern

Equus

, where, “finally, the crowns of the grinding-teeth become longer…. The phalanges of the two outer toes in each foot disappear, their metacarpal and metatarsal bones being left as the ‘splints.’”

In

Cat’s Cradle

, Kurt Vonnegut speaks of the subtle ties that can bind people across worlds and centuries into aggregations forged by commonalities so strange that they must be meaningful. Cortés and Huxley must belong to the same karass (Vonnegut’s excellent word for these associations)—for they both, on the same date, unfairly debased America with the noblest of animals. Huxley was wrong and Cortés, by consequence, was ever so lucky.

Horses evolved in America, through a continuity that extends unbroken across 60 million years. Several times during this history, different branches migrated to Europe, where Huxley arranged three (and later four) separate incursions as a false continuity. But horses then died in America at the dawn of human history in our hemisphere, leaving the last European migration as a source of recolonization by conquest. Huxley’s error became Montezuma’s sorrow, as an animal more American than Babe Ruth or apple pie came home to destroy her greatest civilization. (Montezuma’s revenge would come later, and by another route.)

During our centennial year of 1876, Huxley visited America to deliver the principal address for the founding of Johns Hopkins University. He stopped first at Yale to consult the eminent paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh. Marsh, ever gracious, offered Huxley an architectural tour of the campus, but Huxley had come for a purpose and would not be delayed. He pointed to the buildings and said to Marsh: “Show me what you have got inside them; I can see plenty of bricks and mortar in my own country.” Huxley was neither philistine nor troglodyte; he was simply eager to study some particular fossils: Marsh’s collection of horses.

Two years earlier, Marsh had published his phylogeny of American horses and identified our continent as the center stage, while relegating Huxley’s European sequence to a periphery of discontinuous migration. Marsh began with a veiled and modest criticism (

American Journal of Science

, 1874):

Huxley has traced successfully the later genealogy of the horse through European extinct forms, but the line in America was probably a more direct one, and the record is more complete.

Later, he stated more baldly (p. 258): “The line of descent appears to have been direct, and the remains now known supply every important intermediate form.”

Marsh had assembled an immense collection from the American West (prompted largely by a race for priority in his bitter feud with Edwin D. Cope—see Essay 5 for another consequence of this feud!). For every query, every objection that Huxley raised, Marsh produced a specimen. Leonard Huxley describes the scene in his biography of his father:

At each inquiry, whether he had a specimen to illustrate such and such a point or to exemplify a transition from earlier and less specialized forms to later and more specialized ones, Professor Marsh would simply turn to his assistant and bid him fetch box number so and so, until Huxley turned upon him and said, “I believe you are a magician; whatever I want, you just conjure it up.”

Years before, T. H. Huxley had coined a motto; now he meant to live by it: “Sit down before fact as a little child, be prepared to give up every preconceived notion.” He capitulated to Marsh’s theory of an American venue. Marsh, with growing pleasure and retreating modesty, reported his impression of personal triumph:

He [Huxley] then informed me that this was new to him, and that my facts demonstrated the evolution of the horse beyond question, and for the first time indicated the direct line of descent of an existing animal. With the generosity of true greatness, he gave up his own opinions in the face of new truth and took my conclusions.

A few days later, Huxley was, if anything, more convinced. He wrote to Marsh from Newport, his next stop: “The more I think of it the more clear it is that your great work is the settlement of the pedigree of the horse.” But Huxley was scheduled to lecture on the evolution of horses less than a month later in New York. As he traveled about eastern America, Huxley rewrote his lecture from scratch. He also enlisted Marsh’s aid in preparing a chart that would show the new evidence to his New York audience in pictorial form. Marsh responded with one of the most famous illustrations in the history of paleontology—the first pictorial pedigree of the horse.

The celebrated original figure drawn by O.C. Marsh for T.H. Huxley’s New York lecture on the evolution of horses. This version appeared in an article by Marsh in the

American Journal of Science

for 1879.

NEC. NO

. 123823.

COURTESY DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SERVICES, AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

.

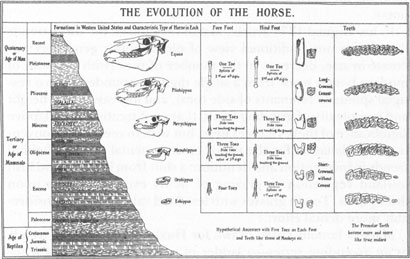

Scholars are trained to analyze words. But primates are visual animals, and the key to concepts and their history often lies in iconography. Scientific illustrations are not frills or summaries; they are foci for modes of thought. The evolution of the horse—both in textbook charts and museum exhibits—has a standard iconography. Marsh began this traditional display in his illustration for Huxley. In so doing, he also initiated an error that captures pictorially the most common of all misconceptions about the shape and pattern of evolutionary change.

Errors in science are diverse enough to demand a taxonomy of categories. Some make me angry, particularly those that arise from social prejudice, masquerade as objectively determined truth, and directly limit the lives of those caught in their thrall (scientific justifications for racism and sexism, as obvious examples). Others make me sad because honest effort ran headlong into unresolvable complexities of nature. Still others, as errors of logic that should not have occurred, bloat my already extended ego when I discover them. But I reserve a special place in perverse affection for a small class of precious ironies—errors that pass nature through a filter of expectation and reach a particular conclusion only because nature really works in precisely the opposite way. This result, I know, sounds both peculiar and unlikely, but bear with me for the premier example of life’s little joke—as displayed in conventional iconography (and interpretation) for the most famous case study of all, the evolution of the horse.

In his original 1874 article, Marsh recognized the three trends that define our traditional view of old dobbin’s genealogy: increase in size, decrease in the number of toes (with the hoof of modern horses made from a single digit, surrounded by two vestigial splints as remnants of side toes), and increase in the height and complexity of grinding teeth. (I am not treating the adaptive significance of these changes here, but wish to record the conventional explanation for the major environmental impetus behind trends in locomotion and dentition: a shift from browsing on lush lowland vegetation to grazing of newly evolved grasses upon drier plains. Tough grasses with less food value require considerably more dental effort.)

Marsh’s famous chart, drawn for Huxley, depicts these trends as an ascending series—a ladder of uninterrupted progress toward one toe and tall, corrugated teeth (by scaling all his specimens to the same size, Marsh does not show the third “classic” trend toward increasing bulk).

We are all familiar with this traditional picture—the parade of horses from little eohippus (properly called

Hyracotherium

), with four toes in front and three behind, to Man o’ War. (

Hyracotherium

is always described as “fox terrier” in size. Such traditions disturb and captivate me. I know nothing about fox terriers but have dutifully copied this description. I wonder who said it first, and why this simile has become so canonical. I also wonder what the textbook tradition of endless and thoughtless copying has done to retard the spread of original ideas.

*

)

Most widely reproduced of all illustrations showing the evolution of horses as a ladder towards progress. Note increase in skull size, decrease in the number of toes, and increase in the height of teeth. The skulls are also arranged in stratigraphic order. W.D. Matthew used this illustration in several publications. This version comes from an article in the

Quarterly Review of Biology

for 1926.

NEG. NO. 37969. COURTESY DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SERVICES, AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

.

In conventional charts and museum displays, the evolution of horses looks like a line of schoolchildren all pointed in one direction and arrayed in what my primary-school drill instructors called “size place” (also stratigraphic order in this case). The most familiar of all illustrations, first drawn early in the century for the American Museum of Natural History’s pamphlet on the evolution of horses, by W. D. Matthew, but reproduced hundreds of times since then, shows the whole story: size, toes, and teeth arranged in a row by order of appearance in the fossil record. To cite just one example of this figure’s influence, George W. Hunter reproduced Matthew’s chart as the primary illustration of evolution in his high-school textbook of 1914,

A Civic Biology

. John Scopes assigned this book to his classes in Tennessee and was convicted for teaching its chapters on evolution, as William Jennings Bryan issued his last hurrah (see Essay 28): “No more repulsive doctrine was ever proclaimed by man…may heaven defend the youth of our land from [these] impious babblings.”