Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (34 page)

Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

We tend to assume that intelligence is a human property, the product of an advanced brain, that arrived on the evolutionary scene billions of years after life began. Only in the Eighties did researchers begin to talk about a silent kind of intelligence built into the immune system. (The turning point came when it was discovered that the neurotransmitters and neuropeptides that brain cells communicate with are present throughout the body.) Witnessing the uncanny precision and accuracy that the immune system employs to fend off disease and heal wounds, some medical writers began to refer to the immune system as a floating brain—its primary home being in the fluid lymphatic system and blood vessels.

What was utterly mysterious was the placebo effect—and its reverse, the nocebo effect—which showed that merely the expectation of getting better can trigger the healing system. This led naturally to the possibility that unseen influences such as emotions and personality traits can drastically affect healing. I found remarkable things to discuss. In one trial patients suffering from nausea were given a pill they were told would cure nausea, and in a certain percentage it did—despite the fact that the pill was actually an emetic, which induces nausea. In one published case, a man with advanced lymphatic cancer, so advanced that his lymph glands were swelling bulges, went

into complete remission over a single weekend. The doctors thought he was on death’s door and therefore untreatable. So they had injected him with nothing more than saline solution, while telling him that he was receiving a particularly new and powerful form of chemotherapy. Later the patient read in the newspaper that this cancer drug had failed in clinical trials. He lost hope, his lymphoma returned, and he died within a matter of weeks.

The mind-body connection wasn’t a curiosity, and no reasonable person could doubt it. Leaving aside the doctors who rejected the placebo effect as “not real medicine,” which was blind prejudice, the doctors who were sympathetic couldn’t figure out how to harness the mind for healing purposes. Various dead ends arose. There was a flurry of interest in so-called type A personalities, people who were impatient, demanding, tense, and susceptible to the triggering of stress. Type As had been correlated with higher risk for a premature heart attack. Yet predictably this neat classification blurred around the edges, and mainstream medicine was too caught up in warning of the dangers of cholesterol to bother with a psychological condition for which there was no drug.

The closer I looked at the mind-body connection, the more I realized that the entire healing system had to be redefined. No one could deny that the mind can do both great harm and great good. Every new finding pointed to an understanding of the body as a holistic system. Billions of cells throughout the body were intimately connected; they eavesdropped on a person’s every thought and mood. This led me to an inescapable conclusion: Medicine would never understand mind and body without seeing them as a single entity. Mind creates matter. That can be observed in brain scans, because those areas that “light up” on an MRI are actually manufacturing brain chemicals, not emitting visible light. Brain scans provide a picture of invisible activity in the mind. The link between injecting someone with saline solution and having his cancer go away had to be mental. For the first time healing came down to consciousness.

Reviewing the literature on thousands of cases of spontaneous remission, I found that the people who had cured themselves of cancer

hadn’t pursued the same program—far from it. Everything from faith healing to grape juice, laetrile from apricot pits to coffee enemas had been tried. These modalities were scorned by mainstream medicine without exception. They had produced a handful of cures but also many thousands of failures. There seemed to be only one strong correlation. People who spontaneously recovered from cancer knew unshakably that they would. One found anecdotes of farm wives who, on discovering a lump in their breast, would visit the doctor once to be diagnosed and then return home, too busy to bother with treatment. Had some of them recovered as their relatives later swore?

I pondered this riddle and decided that something far more powerful than positive thinking must be at work. A turbulent mind can force itself to be positive while remaining disturbed below the surface. Instead of a certainty about their recovery, the people who successfully recovered from cancer may have reached a state of peace, and after that it wasn’t a matter of dread and helplessness whether they got well or not. They had surrendered to the outcome without interference from fear, agitation, mood swings, and the fragile hope that is so common in cancer patients. This state of surrender wasn’t resignation, which is a mask for defeat. Instead, the body was given a chance to draw upon its own healing powers, to regulate itself back into balance. Was this the hidden key?

For Chitra my explorations had no good outcome. Her dread was prophetic. The cancer returned after a brief remission and she died. But this didn’t disprove the notion that the mind holds the power to create change in the body. If anything, the mind-body connection had worked in reverse, turning her fear into illness. Because I hadn’t entirely turned my back on my Western medical training, I asked oncologists how they explained spontaneous remissions. It seemed to me that if even one person recovered from a deadly cancer like melanoma, a massive research effort should be launched. (Melanoma was a good example, since it is highly malignant but also exhibits a higher than usual number of reported spontaneous remissions. We are still talking about a minute number of patients, though.)

The oncologists I spoke to all shrugged. Cancer is a numbers

game, they said. Spontaneous remissions were rare, idiosyncratic cases. Studying them wouldn’t help treat the hundreds of thousands of normal cancers that appear every year. Normal, it seems, meant the total exclusion of the mind.

I can look back on my years with Maharishi Ayurveda as a tight-rope walk where I wobbled but never fell off. In clinical practice I developed a complementary approach. Patients with serious illnesses were treated with Ayurveda but strongly advised to seek conventional medical care. It would have been unethical to do anything else. I squirmed when Maharishi or one of his devoted followers with an MD spoke of Western medicine solely in terms of harming patients and leading in time to a society rife with incurable illnesses. The claim was undeniable. I knew the litany of charges against modern medicine. A shocking number of patients undergo treatments that grossly compromise their immune systems. Others die of illnesses brought on in the hospital, what is known as iatrogenic disease. A fixation on hygiene has resulted in “super germs” that have grown immune to antibiotics. All drugs have side effects, and over time drugs lose their effectiveness. When you paint this grim picture, you can’t leave out the unspoken deaths that occur because people are so dependent on the magic-bullet approach that they neglect prevention—the neglect of self-care is a massive killer.

None of these things can be discounted. They drove me deeper and deeper into alternative treatments. That’s different from jumping into Ayurveda as the one and only solution, which unfortunately is what Maharishi wanted. The flaws of Western medicine made Ayurveda look promising. There was a long way to go, I told him, before the evidence was strong enough to claim that Ayurveda actually cured diseases that Western medicine couldn’t.

Taking this position created the first signs of friction between us. Meetings would drag on, with Maharishi planning a worldwide campaign to “put Ayurveda in every home,” and using inflated rhetoric as a substitute for research. This tactic had worked brilliantly with meditation. TM made claims that took decades to verify with solid

findings. Medicine demands the findings up-front. Maharishi was impatient with that reality. The minute that a new Ayurvedic product was ready to market, he insisted on putting an exorbitant price tag on it (Ayurvedic medicines are generally cheap in India, except for those with exotic ingredients like gold or pearls), and he had only to lift a finger for devoted meditators to rush forward with endorsements about the health benefits they were receiving.

I began to grow restless during the meetings, and then increasingly frustrated. It seemed absurd to be torn in two by opposing forces when they could work together. The tide had turned for alternative medicine. By the beginning of the Nineties the editorial page of

The New England Journal of Medicine

had to confront a fact that deeply distressed the medical establishment: More Americans were going to alternative practitioners than to MDs. It was no longer viable to tell all these people that they were deluded, superstitious, or the victims of scams. Yet that was still the official position of mainstream medicine, which went to extremes of alarmist reactions if need be. When a few cases of poisoning from herbal remedies were reported, a huge cry arose that herbs should be regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, overlooking the fact that fatal reactions to surgical anesthesia and antibiotics were vastly more common.

The rise of alternative medicine was unstoppable, and Maharishi had been early to catch the tide. There was no need to turn Ayurveda into an absolute, an either/or choice between medicine that healed and medicine that killed. What bothered me more, since I wasn’t coerced in any way to talk in either/or terms, was the tendency to turn Ayurveda into a mirror of the drug-pushing that a doctor does all day in private practice. It was herbs instead of pills from Big Pharma, which was promising. Still, the profound basis of Ayurveda was being shifted aside. The real revolution in medicine would come about only through consciousness. People needed to see that matter was a mask for mind. A human being isn’t a machine that learns to think; we are thoughts that learned to build a machine.

I was touring the world using these aphorisms. They were simplistic, but I put all my idealism behind them. People seemed mesmerized,

which to me indicated a yearning for a new way to heal and stay healthy. They knew that they were hopelessly dependent on the medical profession, and yet health is a natural state, one that each person should be able to maintain.

Much of America was too jaded to listen to idealism, perhaps. In other countries, from South America and Ireland to Australia and Great Britain, the reception was more open-minded. I would go on a nationally televised program to talk about the unlimited potential of the mind, with sentences that made the interviewer lean forward with genuine fascination.

“You go to the same place to see the image of a rose as the universe goes to create a star.”

“The macrocosm is the same as the microcosm. Quite literally, your body is the universe.”

“Every cell in your body is part of the cosmic dance.”

Because these things fascinated people, I could distract myself from the troubles that were brewing with Maharishi. Or to be more specific, with his inner circle. Ashram politics are notoriously vicious. The TM inner circle wasn’t an ashram, but people had been jockeying for favor with the guru for years before I arrived on the scene. The international tours grew longer and longer. I sold my practice and within two years resigned my position as chief of staff at the hospital. So far as the media was concerned, my name was synonymous with Ayurveda. Unless they were coaxed into it, reporters almost never added the “Maharishi” part. In that minor slip lay the source of a rift that would never be repaired.

I didn’t see it coming. It wasn’t an impossible strain to feel restless and frustrated. When an enlightened master tells you to compromise some of your beliefs and repress some of your doubts, he knows better than you what is good for your soul. Crusades are fueled by a sense of total righteousness, as long as it lasts.

The path that I was to follow had become clear to me.

20

..............

Finger on the Pulse

Sanjiv

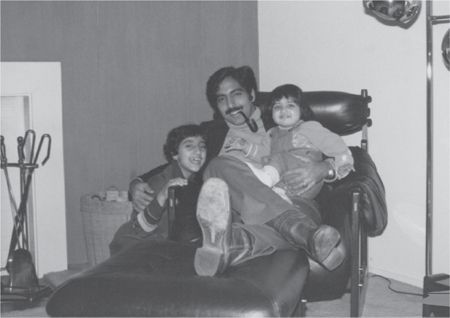

Sanjiv relaxes with his daughters Priya, eight, and Kanika, two, in their Newton, Massachusetts, home, 1978.

W

E GREETED DEEPAK’S SUCCESS

with happiness. He had taken an enormous risk, giving up his successful practice, to follow his heart. That is a definition of courage. I remember thinking of Sir Winston Churchill’s remarks: “Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities… because it is the quality which guarantees all others.” Initially, when Deepak threw himself into his new life with such passion, I was somewhat skeptical about it. Deepak was an intellectual explorer: He’d find something that intrigued him and immediately want to learn everything about it. But in a few months that might well pass and he would be onto a new and glorious pursuit.

For example, after I became a passionate golfer Deepak and I played a round one day in California. He’d been playing the game barely six months but clearly it intrigued him. During the round he asked me why I enjoyed golf so much.

“Deepak,” I said, “it’s outdoors, it’s all about collegiality, focus, integrity, honesty, and commitment.” And as I said this I could see the wheels spinning.