Read Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream Online

Authors: Deepak Chopra,Sanjiv Chopra

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General

Brotherhood Dharma, Destiny and the American Dream (32 page)

“No,” I said firmly. I was vividly remembering the charlatans of my childhood. “Leave now. Be on your way. And go in peace.”

He left just as my niece came out of the store with her soda.

“Chhota papa,” she said, meaning small or younger father. (My kids call Deepak Barra Papa, the older father.) “Chhota papa, what was that man telling you?”

“It was quite uncanny,” I admitted. “He knew that I was a doctor who lived in Boston and had three children and that I worked at Harvard.”

“That’s very strange,” she said. “Because when I was buying my soda a man came up to me and asked me who you were. I told him you were my uncle. Then he asked me all these questions about you and whatever I told him he repeated it into the air in Hindi.”

I laughed, both at my desire to believe him against all scientific evidence and the fact that I had been tricked so easily. That was the India I knew and loved so much, where many things are not what they appeared to be.

In addition to returning to India, members of our family would occasionally come to America to visit us. That gave us the opportunity to see America again through Indian eyes. The young people loved going to the various American amusement parks. They were fascinated by how much American people ate and the fact that they would see so many overweight people at those parks. As they got a little older the shopping mall culture became exciting to them and they loved to go to the large malls with their cousins. And while we wanted our kids to at least appreciate Indian music, before MTV arrived in India our kids were making tapes of the Top 40 hits in America and sending them to their cousins.

Their parents were impressed by how easy everything seemed to be in America. Until the mid-Nineties, when cell phones became available, it could still take many months, sometimes as long as a year, simply to get a telephone line installed. And Deepak enjoyed

showing visitors things like the electric garage door opener that enabled people to perform the amazing feat of opening their door without having to get out of the car! But for most visitors, the biggest adult amusement parks were big-box stores like Costco. Walking through the aisles with them reminded me of Amita’s and my first trip to an American supermarket, which of course was considerably smaller than the big stores. After they got microwaves in India they would always buy the big cartons of popcorn to take back with them.

As a result of the way our kids were raised they identified themselves as Indian-Americans. While many marriages are still arranged in India, we never even approached that subject with our children. But as it turned out Kanika married Sarat Sethi, a distant relative whom she met through the family. In fact, when her future husband’s grandmother was sick, the doctor she generally would go to was my father, Kanika’s grandfather. Her mother-in-law’s cousin is Deepak’s wife, Rita. This is the way it often works in Indian families, even Indian families in America. When Kanika and Sarat began dating they decided to keep it a secret in case it didn’t become serious. When Amita found out who Kanika was dating, at first she was somewhat reluctant, pointing out that we didn’t know him at all. But I felt very differently when I heard about him. I knew I would like him as soon as I found out he was an avid golfer!

Our son, Bharat, had a somewhat different experience. Several years ago he was living and working in Singapore, and he learned that in that culture there was a very distinct pecking order in which respect is given. Because of his name and his appearance it was immediately obvious to everyone that he’s Indian, and that got him to a certain level—but when he started talking and people heard his very American accent they realized he was actually an American, and in Singapore being an American expat got him much higher on that corporate and social ladder.

19

..............

Science of Life

Deepak

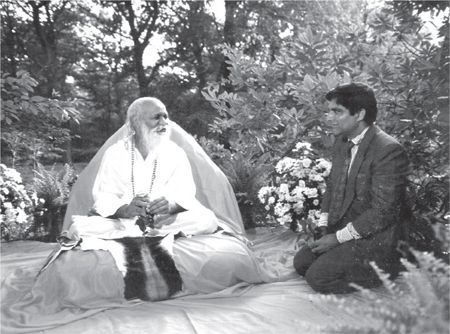

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi with Deepak in a forest grove outside Vlodrop, the Netherlands, late 1980s.

I

N NO TIME AFTER MEETING

Maharishi I made a life-changing decision. Standing in the Boston airport, while still waiting for our baggage to be unloaded, I told Rita that I would be flying back to Washington. I was going to do as Maharishi had asked.

She was quite taken aback. “You’re not even coming home?”

“I can’t. I have to go back.”

My wife knew that I could make impulsive decisions. I had overturned our lives once before, when my fellowship in endocrinology ended badly. But this decision still came as a shock. She had been present for the meetings with Maharishi when he had painted a picture of changing American medicine, with me as his chief spokesman. She loved and respected him as much as I did. But that wasn’t the same as throwing away a thriving medical practice, along with the practical considerations of paying a mortgage and raising two children with college looming in the future.

Maharishi had spent hours assuaging my doubts, and now I tried to reassure Rita. The transition out of private practice wouldn’t be abrupt, I explained, and eventually I could find a buyer for the practice at a good price. I’d make sure that I remained board-certified in endocrinology and internal medicine, so that no one could challenge my professional respectability. And I was chief of staff at New England Memorial Hospital in Stoneham, a position I wouldn’t leave for a while.

Still, I was proposing a huge leap that brought unknown risks with it.

“I know this is right,” I insisted, buoyed by an irresistible wave of enthusiasm. I had no right to announce what our future would be without taking Rita’s opinion into account, but all I could think about was that I had found a calling. Maharishi insisted that I was the

right man to tell the world about his new initiative. He had made a snap decision singling me out of a crowd. Who resists an enlightened master?

I was about to make a snap decision of my own. I would be pioneering a kind of medicine completely different from what is practiced in the West. Because he had made TM a household name, Maharishi wanted to do the same with another aspect of India’s cultural tradition: Ayurveda. As a system of indigenous medicine, Ayurveda went back thousands of years, but its age gave it little credibility in my father’s eyes. Ayurveda was village medicine to him, practiced by vaidyas, the local doctors whose training had scant scientific basis. As part of transforming India into a modern society, the old ways were being ignored, if not discredited. Who needed remedies made from herbs and fruits plucked in the fields? I was being asked to promote something that my father considered superstitious, importing folk ways to America, the most advanced center of medical science in the world.

The irony was lost on me. I was too eager to jump into the abyss. At the airport I walked Rita to the car, and she drove home upset and bewildered. I took the next flight back to Washington, prepared to learn everything about the science of life, which is the literal meaning of Ayurveda (or as the press releases called it, Maharishi Ayurveda—turning everything into a trademark was a lesson in the American way that Maharishi took seriously). Everyone in the movement was delighted by my decision. In short order I was established as the medical director of a facility that the TM movement had bought outside Boston, a sprawling mansion in Lancaster, Massachusetts, built by a wealthy railroad tycoon at the turn of the last century. An imposing brick pile, it had once been surrounded by extensive formal gardens and staffed by household servants. The gardens were dilapidated now, the servants gone, and the interiors in need of extensive repairs. The former owners had used the mansion as a Catholic girls’ school, and they had not lavished care or money on the place.

I wasn’t entirely walking into a vacuum. Meditation had attracted any number of highly educated people, among them some physicians

with much the same credentials as mine. The American and European doctors in TM were enthusiastic about Maharishi’s new campaign, and the Indian ones tried to be, although I suspected they were as baffled as my father. The real connection to this ancient tradition came from the Ayurvedic vaidyas who were brought over in a steady stream from India. Needless to say, they were thrilled that the West was finally paying attention to them. The Washington press stared at this cadre of exotic visitors with undisguised skepticism; Maharishi had as much work to do as when he first won the media over in the Sixties.

The vaidyas presented a contradictory face, as Indians do. They acted like authorities while sometimes breaking out into heated arguments among themselves. (During one public presentation an eminent vaidya got so angry that he ripped a page out of an Ayurvedic text and shoved it in another vaidya’s face to prove his point.) They could be charming and wise, but they also liked to keep their professional secrets to themselves. None were village doctors; these were important figures in their field. The clash with Western culture led to some comical interchanges.

At one press conference a senior vaidya got carried away extolling how Ayurveda could cure any disease. A newsman stood up and asked about AIDS. Was the vaidya saying that Ayurveda had the cure?

Without missing a beat, the vaidya, who was old and a little deaf, said, “Age? Everyone should live to be a hundred. That is normal in Ayurveda.” The reporter raised his voice.

“Not age. AIDS.”

Shocked, the vaidya exclaimed: “Horrible! One man, one woman. That is what the scriptures say.”

It soon became clear that while Western medicine prided itself on establishing scientific facts that every doctor could agree upon, each Ayurveda practitioner prided himself on knowing more than any of his rivals. Certain ancient texts dating back a thousand years before Christ, especially the encyclopedic

Charaka Samhita,

were taken to be authoritative. This didn’t prevent the current practice of Ayurveda

from being a confusing, often contentious field where few assertions were backed up with research that would pass credibility tests in the West. (On their own terms, I hasten to add, the Ayurvedic medical schools did conduct research to prove the efficacy of what they taught, but nothing about that appeared in Western journals. Thirty years later, the situation remains much the same.)

The grandiose claims made by the vaidyas, eager to impress Western audiences, were distressing. My anchor was an eminent Ayurvedic authority named Brihaspati Dev Triguna, the most powerful ally in the field that Maharishi could have hoped for. Dr. Triguna, who was born in 1920, came from my father’s generation. He was a large, imposing figure who exuded authority. When you met him it was almost as if he was holding court, but in fact Triguna saw hundreds of poor patients from his clinic behind the railway station in New Delhi, in a historic section populated by villagers who had migrated from South India.

It added a glow of prestige that Triguna was president of the All India Ayurvedic Congress, but my first attraction was to his diagnostic skills, which were remarkable. My father had built his career on the same skills, which are as much instinct as science. Triguna’s method was entirely based on taking a patient’s pulse. It was startling to watch him touch three fingers to a person’s wrist and immediately diagnose all kinds of maladies, congenital disorders, predispositions to weakness, and so on. When I asked him how he accomplished such a feat, he replied, “Take four thousand pulses first. It becomes clear.”

Triguna also dispensed Ayurvedic remedies of the highest quality, prepared according to meticulous ancient formulas. In essence his practice came down to taking pulses and writing prescriptions all day. I couldn’t adopt such a practice without years of practical training, but I did immediately begin to learn pulse diagnosis. The clinic in Lancaster began to offer

Panchakarma,

the “five actions” used in Ayurveda to balance the body and avert illness. Unexpectedly this became a major attraction. Going through panchakarma was more like a spa visit for the people who came to us. Daily massages with

warm sesame oil and a treatment where sesame oil is gently dripped over the forehead were part of the regimen, along with constant personal care. Dietary advice was tailored to each person’s individual needs. Without knowing anything about Ayurveda’s heritage, celebrities got the word and began to come. When Elizabeth Taylor came for panchakarma, she was so delighted that a regal scene ensued. In departing she slowly descended the huge main staircase of the mansion, with staff members lining her way as she gave each one a silky pashmina shawl embroidered with her monogram.

We had arrived.

With her usual graciousness Rita forgave my sudden leap, and our lives remained intertwined with the rest of the family. Sanjiv and Amita continued to practice meditation. Amita is a pediatrician, but she remembers the spiritual leanings of her father, who died when she was young. On meeting Maharishi, she seemed fascinated by the revival of Ayurveda, and I think she would have explored it more if her busy medical practice hadn’t made so many demands.

The most positive response came from my father, who was dismayed at first that I would throw over my medical career. But as I became more deeply interested in

Vedanta,

the purest and oldest spiritual tradition in India, he took it up too. He and my mother met with Maharishi when he came to his center in Noida, an hour or so outside Delhi. Maharishi would spend hours discussing Vedanta with my father while I sat on the sidelines, rather awed. Once my mother realized that a meeting with the guru was likely to go on for eight or ten hours—Maharishi had indefatigable energy and little need for sleep—she declined to go back.