Blood Sisters (43 page)

Authors: Sarah Gristwood

This lovely miniature shows a vision in which the risen Christ appeared to Margaret of Burgundy in her bedroom, so silently that even her sleeping dog was not aroused.

Like that of her mother Elizabeth Woodville, this portrait of Elizabeth of York is a later version of a single earlier painted portrait type. She holds the white rose symbol of York in her hand.

This depiction of the birth of Julius Caesar reflects not only the childbirth customs of the late fifteenth century but also the high quality of illumination found in Burgundian books and manuscripts at the time.

This tapestry of a hunting scene also shows the courtly pastimes of fishing and falconry. From the marguerites woven into some of the ladies’ hats, it may have been a wedding present for Marguerite of Anjou.

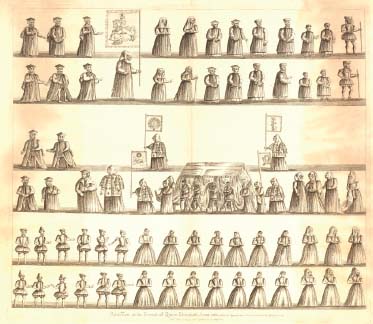

The funeral procession of Elizabeth of York. Margaret Beaufort’s husband Lord Stanley walks directly in front of the bier.

The preparations for a tournament, in the

Livre des Tournois

written by Marguerite of Anjou’s father Rene.

Margaret of Burgundy’s crown may have been made for her wedding, or possibly as a votive offering. The white roses around the rim could suggest the Virgin Mary, as well as being a Yorkist emblem.

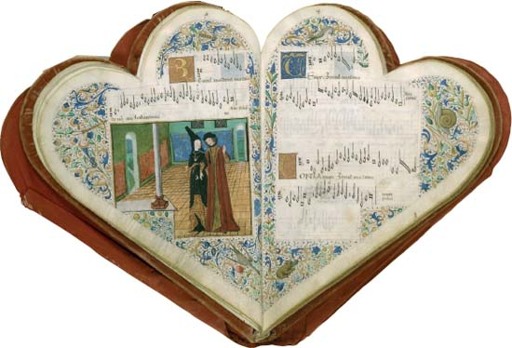

A French collection of love songs, made with hear-shaped pages c.1475.

This illustration for a volume of poems by Charles, Duke of Orleans reflects his twenty-five-year imprisonment in the Tower of London. Behind the Tower itself is a panorama of the city.

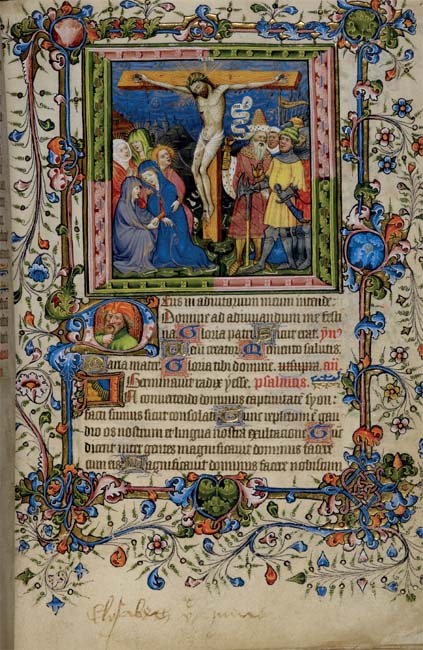

Elizabeth of York has inscribed her name – ‘Elisabeth the quene’ – on the lower margin of this page from a Book of Hours passed down through her family.

Taken from the

Troy Book

of the mid-fifteenth century, the image of the Wheel of Fortune, with a crowned king poised at its apex, would prove all too prophetic for the years ahead.

fn1

Eighteen years later Ferdinand of Aragon was shocked to hear that his wife Isabella had not only had herself proclaimed hereditary monarch of Castile, but paraded through Segovia with a drawn sword carried before her. ‘I have never’, he protested, ‘heard of a queen who usurped this masculine attribute.’

fn2

Perhaps, even, it would not be surprising if Margaret the devout turned with a sense of angry recognition to the religious theories of the day that held maidenhood, virginity, to be the most perfect time of a woman’s life – attempted, in her later rejection of the married state, almost to recreate it. Certainly the iconography was all around – the Virgin Mary, the Maid of Orléans, the Pearl Maiden of poetry, even Galahad and the Grail. The nobly born virgin martyrs – St Catherine of Alexandria, Cecilia, Barbara, Agnes, Agatha, and St Margaret – had become the most popular saints in the England of the day.

fn3

If we want a suggestion of what Cecily might have hoped her relation to Edward would be, we could look to the letter Alice Chaucer’s husband Suffolk had left for his son: ‘I charge you, my dear son, always as ye be bounden by the commandment of god to do, to love, to worship your lady and mother, and also that ye obey always her commandments, and to believe her counsels and advices in all your works …’

fn4

As so often, a look at the personalities offers a slightly different perspective: this Duchess of Norfolk, Katherine Neville, Cecily Neville’s elder sister, had been married off by her father in 1412, in the chapel of Raby Castle, to the Duke of Norfolk. She mulcted his estates after he died; then married a servant in the household; then married a third time to a Viscount Beaumont. She would outlive all her husbands, the last included. It is just possible she – probably in her sixties, rather than her late seventies – was not entirely the passive victim here.

fn5

There had been Henry IV’s dowager queen, Joan of Navarre, in 1419 briefly imprisoned on the accusation of it. There had been Eleanor Cobham, Humfrey of Gloucester’s wife (and thus once Jacquetta’s sister-in-law, in the days when she had been Duchess of Bedford) charged in 1441 by her husband’s enemies and sentenced to imprisonment for life, as well as humiliating public penance.