Blood Sisters (42 page)

Authors: Sarah Gristwood

Elizabeth lies with eyes open and hands folded in prayer, wearing a fur-lined robe and with her feet resting on a royal lion. Torrigiano can never have seen Elizabeth of York – the image was only completed fifteen years after her death – so this may be either a standardised royal image or one guided by her effigy. The result has been called the finest Renaissance tomb north of the Alps, with gilded putti and curling foliage jostling the greyhound and the Tudor dragon. But the point – the point of the whole chapel – is the dynasty.

In the south aisle of the chapel are three free-standing tombs. With Margaret Beaufort lie two of her descendants: her great-great-granddaughter Mary, Queen of Scots; and her great-granddaughter Margaret Lennox, the mother of Mary’s husband Lord Darnley. It is a distinctly crowded setting, given the quantity of white marble beneath which the Scots queen was reinterred in the seventeenth century. In the north aisle are two more of Margaret Beaufort’s great-granddaughters, the two English ruling queens Elizabeth and Mary. Since Henry VIII lies at Windsor – with Edward VI merely placed beneath the altar in Henry VII’s chapel – this has wound up being a monument not only to the Tudors as such, but to the distaff side of history: a ‘Lady’ Chapel in honour, appropriately, of the Virgin Mary.

None of the other women in this story has a tomb as visible as these in Westminster Abbey. Elizabeth Woodville, interred with so little ceremony, at least got to share, almost unnoticed, her husband’s tomb at Windsor. Anne Neville is known to be buried in Westminster Abbey, but the site is not recorded. And though Cecily Neville is buried as she planned at Fotheringhay, the place never became what she had intended, a memorial to the Yorkist dynasty; indeed, by Elizabeth I’s day the tombs had fallen into such disrepair that she ordered to be them tidied away. Even Margaret of Burgundy’s tomb in Malines was ransacked in the sixteenth century – by local iconoclasts, Spanish troops or English mercenaries – and today no trace of any memorial remains. Margaret of Anjou was buried as she requested with her parents at Angers – evidence that the war in the country which should have been her marital home had not gone her way.

Everything that is known about these women suggests that their main imperative was dynastic – genetic. And the blood of Elizabeth Plantagenet and Henry Tudor – and therefore the blood of Margaret Beaufort, Elizabeth Woodville and Cecily Neville – still runs in Britain’s royal family. This legacy would surely outweigh whatever personal price they had to pay. Amongst the women of this Cousins’ War, Margaret Beaufort fought hardest and most successfully for her bloodline. She is also the only one to leave another sort of legacy – a legacy of works.

1

The links between these women and their descendants would continue long after they were dead. The deadly dispute between cousins continued for the next century, with its contests mostly fought away from the battlefield, in arenas where women could compete more visibly. Elizabeth of York’s granddaughter ‘Bloody’ Mary would dispute the throne with her kinswoman Jane Grey (descended from Elizabeth’s younger daughter Mary); Elizabeth Tudor would be forced to execute the Queen of Scots, descended from Elizabeth of York’s elder daughter Margaret. But out of their combined experience, out of the different models of female agency they embodied, would be born something more productive.

England’s consort queens, from the Conquest to the Tudors, demonstrate a gradual move towards mere domesticity

2

– from the time when a strong woman ‘will be counted among the men who sit at God’s table’ to one when any sign of such ‘manful’ strength was a source of profound unease. And yet, in the century ahead, the idea of the strong woman (something then seen almost as a third sex) was about to reach its apogee. Elizabeth I, perhaps the country’s greatest monarch, played upon all the ambiguities of gender, not least in her famous speech at Tilbury. She reconciled, at least for her own lifetime, the problem with which Marguerite of Anjou had grappled in vain: that of reconciling the requirements of rule and the pressure to be ‘womanly’.

That later Elizabeth, of course, was a woman whose undoubted contribution was neither genetic nor dynastic. That has been, to all women since, her lasting legacy. If Elizabeth of York was Elizabeth I’s physical progenitor, then perhaps she could trace back to Marguerite a different kind of ancestry. Perhaps, even – however cruelly the wars had told upon her – that fact gives to Marguerite, too, a share in the ultimate victory.

John Talbot, in his Garter robes, presents a copy of the beautifully illustrated Shrewsbury Book to Marguerite of Anjou, shown hand in hand with her new husband Henry VI. Daisies – Marguerite’s personal emblem – decorate the lavish borders.

The stained-glass Royal Window in Canterbury Cathedral shows the figures of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, with their sons and daughters to either side, kneeling at prayer desks. The royal figures originally flanked an image of the Crucifixion, but the window was damaged by Puritan iconoclasts in 1642.

Believed to have been painted by Rowland Lockey in the last years of the sixteenth century, this image of the ageing Margaret Beaufort reflects her reputation for piety. Margaret’s emblems – the mythological beast called a Yale, the portcullis and the red rose – adorn several Cambridge colleges of which she was patron.

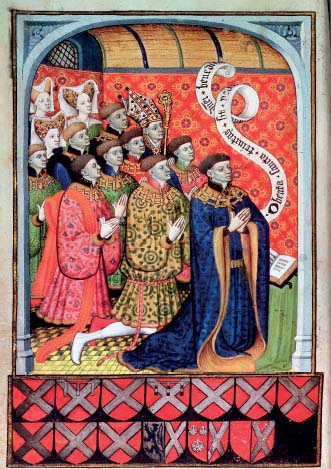

Cecily Neville’s father, the Earl of Westmorland, flanked by the many children of his second marriage, in a French illustration from the fifteenth century.

Portraits of Elizabeth Woodville – mostly sixteenth-or early seventeenth-century copies of one original portrait type – show the high forehead and elaborate headdress that were a fashion of the day.

Anne Neville, depicted here in the Rous Roll, is shown in her coronation robes with orb and sceptre.

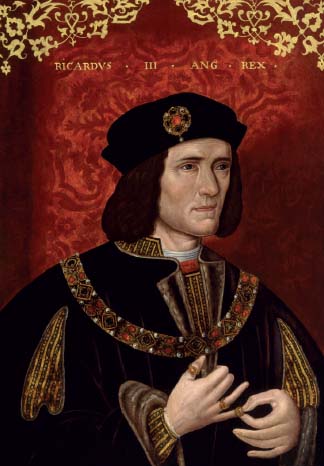

Portraits of Richard III often show a more personable figure than his later reputation might suggest.